Lockett case shows dilemma of doctors involved in executions

Published 3:00 pm Friday, March 27, 2015

OKLAHOMA CITY — As the doctor entered the prison, he was already torn about his role in the execution of Clayton Lockett.

Warden Anita Trammell said she met the doctor as he arrived at Oklahoma State Penitentiary last April 29.

“I’m just glad I happened to be down there or (he) may have just walked out,” Trammell said. “(He) said, ‘I’m just filling in anyway. I don’t know why I’m even, why I even, you know, agreed to do this.”

Two other doctors had already said no to attending the double execution planned for that night. The physician — identified only in investigative transcripts as “doctor” — agreed to step in only days earlier.

Such duty challenges the oath that doctors take upon entering their profession. They pledge to do no harm and minimize suffering, yet when asked to serve as a sword of justice, they can find themselves conflicted.

That contradiction, between Hippocratic Oath and capital punishment, is the source of heated controversy within the medical community. Most physicians groups — including the American Medical Association — strictly forbid members’ involvement in such acts, with the exception of prescribing sedation beforehand or, later, signing a death certificate.

For those reasons, states are finding it harder to recruit doctors to participate in executions, said Dr. Steven Miles, an internist and professor of medicine and bioethicist at the University of Minnesota.

“Executions are not considered a medical act,” he said. “Basically a doc’s role is that of a healer, and this is not a healing act which is serving the patient’s interest.”

Anonymity isn’t enough

In hopes of avoiding that conflict, states including Oregon and Georgia have passed laws that forbid sanctions against medical professionals involved in executions. Some states, including Oklahoma, have laws that keep secret the identities of participants in the execution.

Laws that veil the process in secrecy make it impossible to know just how many states require a doctor’s involvement, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, which monitors capital punishment.

Even promises of anonymity aren’t enough incentive for many doctors, said Miles. Some states, unable to find volunteers, fly in doctors from elsewhere.

“Despite shield laws to protect them, they will, if identified, will probably not face a medical (license review), but will face enormous public scrutiny,” he said, adding that he personally believes that doctors should have no role in executions.

Others feel that doctors should be involved, however.

Last year The Constitution Project, a national group that claims members on both sides of the death penalty debate, made the controversial recommendation that licensed, practicing medical workers should be involved in the medical aspects of executions.

The group acknowledges that its view conflicts with the long-held policies of various medical societies, and that nobody should be compelled to participate.

Drug-damaged veins

The doctor’s account of Lockett’s execution, and that of Trammell, the warden, were made public with the release of more than 5,200 pages of documents related to an investigation into the 43-minute procedure in which Lockett is said to have writhed on a gurney. The state Department of Public Safety withheld names of those involved in the procedure.

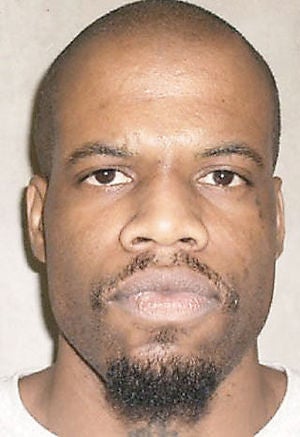

Lockett, 38, had been condemned to death in 2000 for the kidnap, rape and tortuous murder of a teenager. The second execution planned for that evening, of Charles Warner, was ultimately postponed because of the problems with Lockett’s lethal injection.

The doctor told investigators he wasn’t supposed to have any role but pronouncing Lockett unconscious and declaring him dead.

The trouble started almost immediately. A paramedic who supposed to insert two IV lines into Lockett couldn’t find a suitable vein.

The paramedic and doctor immediately recognized what prison medical professionals in all of Lockett’s years had apparently failed to note — Lockett was an admitted intravenous drug user whose habit destroyed the viability of many veins. Lockett told the two that he used those drugs up until three to four months before his execution, according to the doctor’s account.

Trammell said she was shocked to hear that, and also that it had gone undetected by prison medical staff.

While confused about how Lockett could have used such drugs behind bars, the doctor said he was dismayed that he wasn’t informed of it prior to the procedure. For the paramedic inserting the IV, it meant poking Lockett over and over with a needle.

Trammell said she could tell Lockett was in pain. Either the doctor or paramedic tried to place a hand on Lockett’s head to calm him, the warden said. The doctor numbed as best he could the area of the injection, near Lockett’s groin, to reduce the pain.

Usually prison officials use two IVs to administer a fatal cocktail of drugs during a lethal injection. But, the doctor said, finding just one vein was enough.

“I wasn’t willing to do any more,” he told investigators, adding that the prodding and cutting down to a vein was extremely painful for Lockett.

Trammell ordered a sheet placed over Lockett’s groin to protect his dignity. She then ordered the blinds lifted and the execution to commence.

‘He’s coming out of this’

Nothing seemed to happen — at first.

“I was watching his face and his expressions, and nothing was happening. I mean, nothing was happening. Nothing,” Trammell said. “You know, he was trying to be real patient, it was obvious. He was laying there with his eyes closed, and I mean, it just looked like nothing was happening for a while.

“And then he’d open his eyes, and he’d kinda look around. And at one point he looked over at me like, ‘What, what’s taking so long?’ and I mean, that’s just the expression he gave me.”

Minutes later, the doctor pronounced Lockett unconscious, and the rest of the drugs were administered.

Then Lockett started moaning and convulsing on the gurney. The doctor walked over, lifted the sheet, and discovered a bubble larger than the size of a golf ball where the drugs were coalescing because the IV had become dislodged.

The doctor whispered in Trammell’s ear that things weren’t going according to plan.

Said Trammell: “I thought (Lockett) said something, but I can’t remember exactly what it was because … I was kind of panicking, thinking, ‘Oh my God, he’s coming out of this.”

She ordered the blinds lowered.

Can he be revived?

Trammell demanded to know if there were enough drugs to finish the job.

The doctor said he purposely didn’t want to know what drugs the prison was using to execute Lockett, though he later told investigators that he was aware they had planned to use midazolam, the sedative that acts as an anti-convulsant.

The doctor said he knew it to be a “short-acting medication” that wears off in as little as 20 minutes from the moment it’s injected, depending on a person’s metabolism.

Miles, the medical ethicist, noted that midazolam, unlike many drugs, has no dosage known to be lethal. It is similar to sedatives that are often abused, he noted, meaning that someone could build up an “enormous tolerance” to it.

With Lockett’s execution stalling, the doctor and those in the execution chamber were at a crossroads, according to their interviews. Should they let Lockett’s death proceed or try to reverse the procedure and save him?

The doctor said Trammell asked, “Can we resuscitate him?”

“I said, ‘Do you want me to? Then we’ll have to take him to the ER,'” he said.

“Then somebody in the room said, ‘No we can’t do that,'” he said.

The doctor said he could reverse the effects of the midazolam, but doubted that the medication to do it was available at the prison.

To revive Lockett, he said, he would have needed to perform CPR then provide advanced cardiac life-support until they could get him to a hospital.

To offset the effects of a second execution drug, he could give him glucose and insulin at the hospital.

No efforts to resuscitate Lockett were made, according to the interviews.

Lockett’s pulse continued to slow.

‘Dying the whole time’

Tension and frustration mounted in the room as Lockett’s pulse continued to fall, and Trammell asked repeatedly if he was dead yet.

“(He) got pretty frustrated with me,” Trammell recalled of her repeated demands to the doctor to pronounce Lockett dead.

“They wanted me to declare him deceased,” the doctor said, adding that it wasn’t going to happen until Lockett was completely pulseless.

“Now, I don’t know if he could have been resuscitated or not. I doubt seriously that he could have been,” he said.

Alexandra Mullock, a professor of medical law with the United Kingdom’s University of Manchester, whose research includes ethical analysis, said a doctor’s involvement in executing prisoners is considered a breach of Hippocratic tradition in her country.

The exception is a patient who is dying and asks for medication to hasten death.

“It becomes more tricky if a health professional is present, not to kill but to make sure the execution is done in a way to minimize suffering,” she said.

“And in this capacity, if the patient did not die immediately, I would argue that a health professional would have an obligation to save the patient and preserve life,” she said.

That, she said, contradicts the purpose of an execution.

“There is no ethical way for a health professional to take part in executing people,” she said.

In her interview with investigators, Trammell defended the choices made in the moment.

While Lockett’s death wasn’t sudden, she said, he faded until the doctor finally pronounced him dead.

“It’s not like at 7:06 he had a massive heart attack and died,” she said. “He was dying the whole time, in my opinion, he was dying the whole time.”