Local veteran reflects on service as helicopter pilot

Published 1:47 pm Monday, January 29, 2018

- John Edgemon

By Beth Alston

Edgemon chosen for revenge mission

AMERICUS — John Edgemon of Americus is an American hero. Modestly, he says he was just doing his job, but there’s a lot more to it than that. There is a story behind the story.

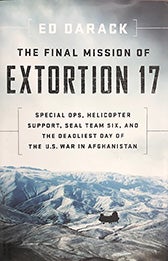

“The Final Mission of Extortion 17 — Special ops, helicopter support, SEAL Team Six, and the deadliest day of the U.S. War in Afghanistan”, by Ed Darack, was published in fall 2017, by Smithsonian Books.

The well-researched book relates the story of the final flight of Extortion 17 on Aug. 6, 2011, near Kabul in Afghanistan, when the enemy shot down a U.S. Army CH-47D Chinook helicopter, killing all on board. Extortion’s mission was to reinforce a unit of Army Rangers in Wardak province.

The well-researched book relates the story of the final flight of Extortion 17 on Aug. 6, 2011, near Kabul in Afghanistan, when the enemy shot down a U.S. Army CH-47D Chinook helicopter, killing all on board. Extortion’s mission was to reinforce a unit of Army Rangers in Wardak province.

Darack’s background on the soldiers and their families lends even more humanity to a heartbreaking story of loss and bad fortune.

Americus’ own John Edgemon, who, as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army, flew helicopters during the conflict, recalls vividly the mission that gave full payback to those who shot down Extortion 17, killing all 38 humans on board: 25 special operations personnel, five U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve crewmen, seven Afghan National Army Commandos, one Afghan interpreter, and one U.S military working dog. Edgemon was part of Operation Ginosa, which can be described as a revenge mission.

“The reason the bad guy got killed is he shot down the Americans and then he bragged about it,” Edgemon said as he sat in the conference room of the Americus Times-Recorder’s offices recently.

Edgemon served in the U.S. Army for 8.5 years, signing up exclusively to fly helicopters. It was in his contract that he would attend helicopter school, which he did, at Fort Rucker, Ala. He had learned to a fly a small airplane, a Cessna 172, at Souther Field near Americus. He liked aviation so much he wanted to fly helicopters for the Army.

“They’ll train you for free,” he said. “I wanted to learn to fly the closest air support helicopter and be the hero to save the day when soldiers call for help. That was my fantasy. That was my goal and then I got out, two years after the incident.”

During his years of military service, Edgemon was deployed for a year in Korea, a year in Iraq and a year in Afghanistan where the Ginosa mission occurred.

“That’s why a lot of people get out [of the military], because if I hadn’t gotten out, in two weeks I was going back to Afghahistan for eight months.”

Edgemon, now 40, said that many of those service men and women who are deployed to the Middle East “get out because they get tired of living in the Middle East half of their life. You live in a tent and have someone using the toilet right beside you. It gets old after a while. Having your own bathroom is a luxury. People forget about that. But at least we had bathrooms.”

There was absolutely no alcohol in Afghanistan for military forces.

The policy is not so much awareness of Muslim culture, but we all carried around loaded guns 24 hours a day,” Edgemon said. “Mixing guns and alcohol and a bunch of young men is asking for trouble… That’s my theory. They never posted that but there was no alcohol at all.”

It was mostly work during deployment, he said.

“Every soldier got two weeks off during their one-year deployment and could pick out any airport they can land at, but 90 percent flew home,” Edgemon said. “But you could tell them you want to go to Paris and get 15 days off throughout the year.”

Edgemon said the first thing he wanted to do when he came home was to stop by a convenience store and drink a beer.

“At the time you haven’t had a beer in 10 months. So, you just want to drink a beer, eat some junk food and take a shower in your own bathroom … simple pleasures,” he said. “And sleep at night and not worry about getting attacked or bombed. We always had rockets coming in and blowing up. We were in these bases, F.O.B., about 3,000 people and it’s pretty secure. There are guards and walls, barbed wire but the enemy would launch rockets into the base. A lot of times twice a day and with a lucky shot they’ll hit and you’ll think, ‘wow, it didn’t hit me.’” He said he had them hit as close as 30 yards away. “Two of them hit that close one time,” he said. “Glorified bottle rockets that the Taliban fired into the base.”

Edgemon explained that an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) was used to down Extortion 17, not a guided missile.

“They’re [RPGs] cheap,” he said, “1950s and ‘60s technology, readily available. Very good at shooting tanks; that’s what they were designed for. But they have many uses.”

Edgemon started in flight school flying a Bell 206 Jet Ranger, a typical four-door helicopter used by medi-vac, news crews, law enforcement. Then he advanced to the AH-64 Apache helicopter, an attack helicopter.

“Hueys carry people around,” Edgemon explained. “Apaches are just two pilots and have guns and missiles hanging out on the wings. Cannons, rockets and missiles. We’re like the Huey Cobra was in the ‘60s. So, we’re the attack helicopters. We don’t haul people around; we don’t haul cargo. We’re the security guards in the sky,” he said. “Chinooks carry personnel and equipment, in use since Viet Nam and it’s still the best to do it.”

Edgemon said it takes about three times longer to learn how to fly a helicopter as an airplane.

“I say someone of average intelligence can fly an airplane or a helicopter. You’ve just got to be dedicated … and it’s going to take you a month or so to figure it out, the basics,” he said.

Of the downing of Extortion 17, Edgemon said he had worked with them, but didn’t know any of them personally.

“I didn’t know their names because they had call signs code names because it was secret,” he said. “I worked with them. I went to briefings with them but I didn’t hang out with them. Same with the pilots, too. I just hung out with them. The SEAL Team Six, I dealt with the Gold Team. It was the Red Team that got bin Laden three months before. These guys and the pilots, we all flew out every night. I worked with them every night for a month before they were shot down. They’d land at houses in the middle of the night, raid them, capture or kill … They’re top secret. That’s the same thing they did with bin Laden. The public makes a big deal out of bin Laden mission but it was the same type house raid the Navy SEALs did most nights in Afghanistan. They knew how to do it whether it was bin Laden’s house or anyone else’s house. It was just another night for them, too.”

Edgemon was on duty the night of the take down of Extortion 17.

“My guys in my platoon were actually guarding Extortion,” he said. “I used to guard it every night but that night I had gone on to another mission. My guys were guarding Extortion and they called for help. I was one of the guys who reacted and flew to the crash site.”

Edgemon said he arrived about 45 minutes later and saw the burning wreckage.

“At the time … you never claim that anyone’s dead yet; that’s not our call,” he explained. “We say ‘no movement on the ground, looking for survivors.’ We didn’t know if there were enemy huddling next to a tree that could get us. I’m looking for bad guys and looking for the Americans at the crash site. Plus, we’re a little nervous, they shot down one helicopter, they might shoot me down next.”

Edgemon said he hovered within 1,000 feet of the crash site. “Flew right overhead at 1,000 feet to get good looks. … It was at 3 a.m.” He said it was a big fire and they never saw anyone moving.

“We saw all this in night vision which requires training. One goes on the head and magnifies the starlight and whatever other light sources exist 1,000 times,” he said, adding that they also employed infra-red that picks up heat.

The shooting down of Extortion 17 received a lot of media attention.

“Right after the crash, the army sent in every available person, about 1,000,” Edgemon recalled. “For three days we provided 24 hours overwatch.”

It was during that time that the brass came up with Ginosa, a retribution mission, to locate the enemy RPG shooter and take care of business.

“Two and half days later, the night I show up for work on shift we’re told that the CIA has been tracking the guy (who shot down Extortion),” Edgemon said, and “ya’ll are going to go out tonight and kill him.”

They had about an hour’s notice before taking off.

Edgemon was asked about his adrenaline levels when he learned of this mission, and his involvement.

“We were excited,” he said. “We’d been in a lot of shoot-outs. Going out and shooting people is a way of life for us but that night it was more personal for us, more dramatic. We knew it would make the national news. But the main thing was ‘I hope we get him upon first engagement because you don’t want the target to survive and get away which makes him more paranoid in hiding and more difficult for the CIA to reacquire.’ You don’t know what you’re up against. There’s a lot of pressure. You know, too, that there are drones overhead that are watching and they send a video feedback to the headquarters (at Bagram Airfield) so you’re being watched as you’re shooting this guy. That’s nerve-racking. During a similar capture/kill mission two months before Operation Ginosa, I had some of the worst shooting of my career as the high ranking military personnel in the situation room were watching. I shot at a guy and missed,” he said. “Over the next 20 minutes, headquarters anxiously watched my Apache and my helicopter wingman continue to shoot and miss the target individual with cannons until I launched a missile that destroyed him. We didn’t realize at the time but this experience helped prepare and train us for Operation Ginosa which would occur two months later.”

Ginosa was a five-hour mission, Edgemon said.

“Afterward you replay in your head what you could have done differently,” he said, “because it’s so intense, and so fast at the time. You replay the scenario and try to figure out what you did wrong, did I look stupid? You play that over and over.”

The technology of war today is beyond sophistication.

“It’s so complicated that sometimes people don’t even know what’s going on,” Edgemon said. “I don’t even know what all’s flying over my head. On a typical mission and this one included, you’ll have the bad guy here, and we’re here, and you’ll have other planes here and surveillance planes and they say stay between 2,000 and 3,000 feet because there’s someone at 3,000 to 4,000 feet. It’s like this beehive flying above the ground. That’s the modern army and how they do it. And also, you’ve got Army, the Air Force, and the Navy and you’ve got people from international countries. It’s all integrated; you don’t know who’s working for who.” But it works.

Of Ginosa, Edgemon said, “At last we got some revenge. We killed the guy before the funerals [of the Extortion 17 victims] were held.”

Edgemon said Aug. 6, 2011, was possibly the single deadliest day due to enemy fire for American military since 1968, during the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. “Non-combat, training missions and terrorist attacks have killed more but not due to enemy fire,” he said.

During the Ginosa mission, how could Edgemon and the other Apache tell which was actually the one who had fired the RPG that brought down Extortion?

“They can tell from the cameras; I couldn’t see it but there’s enough surveillance in there that they can see individuals,” he said. “They’re relaying coordinates and we’re saying it too and I could see it through heat vision … In the actual shooting, we watched the car with several guys in it for about 45 minutes; we couldn’t shoot. … Someone else owns the target and I’m just their attack person who goes after someone when they tell me to. I’m working for him. After about 45 minutes, they said ‘let’s start shooting now’ (two Apaches). There was an Air Force jet with bombs on it and a plane with guns on it (AC-130 gunship, like in the book).”

Edgemon went to explain how it happened. “The wooded area was bombed first,” he said. “And then the AC-130 plane with big guns keeps shooting at it and then they were told to stop shooting. The Apaches then came in as scavengers to look for anybody still moving around, because we can fly close and low. If you see a hot body out there you can reengage the target, and sort of fly around and see what you can see; that was our job. We were the last ones to go in and pick it, and we shot at it, too, from a distance, before going in close to pick at it. It’s not perfect; there’s a lot going on. There are six people moving in different directions, trees everywhere.”

Edgemon said the enemy uses guerilla warfare. “The enemy sneak up and attack our ground soldiers. Our military is like cops riding around with the big American flag and the enemy just pop out at them,” he said. “Most of the time our infantry can easily counterattack, but when they need reinforcements or are outgunned, Apache helicopters are frequently called in for airstrikes and birds-eye surveillance. Apaches arrive more quickly compared to armored vehicles on rugged roads; we will also fly up the mountainside to shoot hidden snipers that are hard to reach by climbing. When Apache gunships arrive, the Afghan enemy always shifts from offense to defense. They also had the same experience from the Russian Hind attack helicopters in the 1980s.”

Edgemon flew about 1,000 missions during his deployments.

“On average one a day but some days two or three,” he said. “But a mission means a tasking. Engagement is only about 1 percent of the time. It’s sort of like deer hunting, 99 percent looking and 1 percent shooting. A lot of missions you are just looking and you don’t see anything. Sometimes you feel like a bored security guard in an empty Walmart parking lot. You’re just looking over nothing and then some days it’s exciting. The most exciting is when you see something bad happen and then you get to shoot and that’s kind of exciting, too. It’s a lot of work every time. We have procedures. The helicopter has video cameras just like police body cams.”

Ginosa was also a secret mission, Edgemon said, “so secret that the people involved in the mission only had one hour notice. It was our guys (on Extortion 17’s final mission), so it was revenge. All the guys we work with every night were dead and we were sitting there with no mission.”

Edgemon was asked why he didn’t go with a military career.

“I never wanted to make a career out of it,” he said. “I got tired of it because they control your life and what you do. It was a great experience though.”

Edgemon’s take-away from military service?

“I think discipline is important for people,” he said. “And being prepared and thinking of all the contingencies and possible scenarios of what could go wrong and how to prepare for it.”