Till death, not distance: The separation and reunion of Peter and Catherine August

Published 3:33 pm Thursday, July 25, 2019

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Evan A. Kutzler

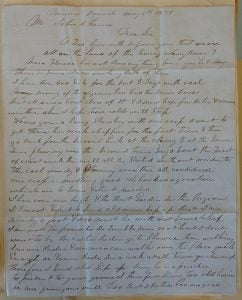

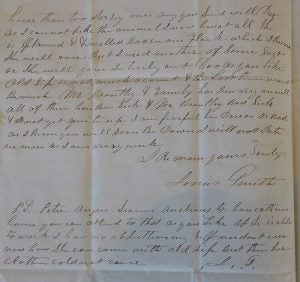

Buried at the end of an 1851 letter about plantation management is a story of family separation and the hope for reunion. Peter and Catherine August were an afterthought, a literal “P.S.” in the words of a white overseer on the Domino Branch plantation in Sumter County to his powerful boss in Bibb County. Jonas Smith, the semi-literate overseer, knew what information mattered most to his employer. Two enslaved women, Mara Florida and Nancy Boson, were too sick to work and the corn was “nee high.” Smith also planned to send “old man Siss,” an enslaved preacher, to Bibb County to bring back a good horse. Finally, despite his poor spelling, Smith conveyed Peter August’s plea to the man who claimed to own him. “P.S. Peter Augus[t] Seams anchious to have cathrine home,” Smith wrote. “You can attend to that as you like. If S[h]e is able to work I hav[e] no objecthon my self nor dont care naw how. She can come with Old Siss But then her clothes could not come.”

Buried at the end of an 1851 letter about plantation management is a story of family separation and the hope for reunion. Peter and Catherine August were an afterthought, a literal “P.S.” in the words of a white overseer on the Domino Branch plantation in Sumter County to his powerful boss in Bibb County. Jonas Smith, the semi-literate overseer, knew what information mattered most to his employer. Two enslaved women, Mara Florida and Nancy Boson, were too sick to work and the corn was “nee high.” Smith also planned to send “old man Siss,” an enslaved preacher, to Bibb County to bring back a good horse. Finally, despite his poor spelling, Smith conveyed Peter August’s plea to the man who claimed to own him. “P.S. Peter Augus[t] Seams anchious to have cathrine home,” Smith wrote. “You can attend to that as you like. If S[h]e is able to work I hav[e] no objecthon my self nor dont care naw how. She can come with Old Siss But then her clothes could not come.”

Historians probe records not only for answers but also for new questions. Who was Peter August? And Catherine? Under what circumstances were they separated? Were they reunited? What was lost and gained in the process? These questions confronted me when I held the original letter at the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia. These were the whispers of an important story. Now when I take Lamar Road to “Booger Bottom,” I cannot help but think about Catherine, Peter, and the plantation along the road that now bears an enslaver’s name.

Relocation to Sumter County

Peter and Catherine August were unwilling pioneers forced to settle land seized by whites from Native Americans. Their journey personifies a demographic wave that shaped the history of the “Black Belt” and the Deep South. In January 1847, John B. Lamar moved one-third of the people he held in slavery from Bibb County to Sumter County. He planned to send another third in a year and leave the remainder in Bibb County. Lamar was one of many men who envisioned his field “hands,” a euphemism for people, growing cotton — and, by extension, money — in Southwest Georgia. By 1860, there were more enslaved African Americans in Sumter County than whites. Lamar owned 193 people. The experience of slavery was more common than freedom.

The men, women, and children sent to Sumter County in 1847, are recorded by name. Lamar kept meticulous records that detailed the people, animals, crops, farm tools, and household items down to the quill and the bottle of ink. He arranged enslaved people by family, an indication that he had no confusion over the humanity of the people he enslaved. The Augusts were a childless enslaved couple who came from Bibb to Sumter County together before being separated. The meticulous accounting of Lamar’s property hints at Sumter County living in 1847. In addition to plantation work, Catherine made her and Peter’s clothing from 18 yards of cotton Osnaburg. In the fall, she made winter clothing from 15 yards of wool and nine yards of cotton. They each had one blanket, one hat, and one pair of shoes. Catherine was about 18 years old.

Separation

The Augusts’ separation occurred between 1848 and 1851, but no one recorded the exact circumstances of their parting. Jonas Smith’s openness to have Catherine August back if she was “able to work” hinted that she had been unable to endure — or had actively resisted — being the field “hand” to an enslaver’s will. Perhaps the hope of reunification compelled Peter August to work harder in the 1850s. More than a decade older than Catherine, Peter picked more cotton than all but four enslaved men and women on the plantation. If the two saw each other in 1850s, plantation documents did not record the meeting.

The Civil War years did not make reunification inevitable. News of the bullet that pierced Lamar’s left lung reached Southwest Georgia about the same time as reports of a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. While the latter may have inspired hope, the death of an enslaver was no time for celebration. As the Augusts would have known, the distribution of a dead enslaver’s estate to white heirs often meant the permanent separation of black families. Lamar’s will specifically called for selling his property and distributing the proceeds. The Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, and the U.S. army ended slavery before such a dreaded sale occurred for the Lamar estate.

Reunited in freedom

It is rare that historians can trace an individual’s or a family’s journey from slavery to freedom. What is unique about Catherine and Peter is that an individual record of life during and after slavery exists at all. What did freedom mean? One glimpse of life in 1870 offers a couple answers. By then, the couple had reunited in eastern Sumter County and they had the legal right to marry. Peter worked as a farm laborer, but he apparently chose not to work for John Lamar’s immediate successors at old Domino Branch. He also saved money, $350 to be precise, and Catherine did not have to work in the fields or in a white person’s home. A third household member hints at reunification across generations. Seventy-year-old Gracie Bird, possibly Catherine’s mother, lived with them.

Unanswered questions abound. Plantation and census records suggest Catherine never had children. Was this a consequence of forced distance? Where the two lived after 1870, and for how long is also unknown. Most importantly, in one of the cruel legacies of forced illiteracy, the Augusts could neither read nor write. Therefore, how Catherine or Peter would tell her or his story is a mystery. Any honest assessment must admit that the meaning of their experience is uncertain. Remaining records offer only a passing glimpse into the complicated lives of a couple separated in slavery and reunited in freedom.