On New Era Road: A Rosenwald School’s Decline

Published 10:22 am Wednesday, January 22, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Evan Kutzler

New Era Road is a study of contrasts. It once led to a sizeable community; now vacant houses reflect long-term economic changes and the challenges of rural preservation. New Era Road once had two schools within one mile of each other. The brick school, built with public funding for local white children, is now a single-family residence. A wooden school, built with a combination public and private funds for African American children, sits vacant between a small Baptist church and the New Era Substation. This school, known as Shady Grove, impresses even in advanced neglect. It is also a “Rosenwald School,” the last of its kind in Sumter County.

What is a Rosenwald School?

Rosenwald Schools developed in response to the unequal public education in the early twentieth century. After Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of segregation, the racial gap in public spending widened until white schools received, on average, twice the annual allocation as black schools. Allocations for school buildings could be even more unequal. In the early twentieth century, white schools in Georgia received 90% of the total allocations for educational infrastructure. The lack of public support left black parents, students, religious institutions, and philanthropic organizations to close the gap though a “second tax” of private monetary and in-kind donations.

The Rosenwald Fund emerged as a push against unequal education in the 1910s. The school-building program began as a partnership between two powerful men: Booker T. Washington, founder and president of Tuskegee University; and Julius F. Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company as well as a member of the Tuskegee board of trustees. After Washington died in 1915, Rosenwald expanded the program, formalized funding requirements, and opened a regional office in Nashville, Tennessee, to oversee the program. In less than two decades, the program led to 5,000 new black schools in 15 southern states. By 1932, Georgia had more than 250 Rosenwald Schools representing a private contribution of $1,378,859 to black education. At that time, about one of every three black children living in the rural South—and 35,000 children in Georgia—attended a Rosenwald School.

In funding new schools, Rosenwald hoped to extend, not replace, public funding and community involvement. Rosenwald Schools, like their predecessors in rural churches and one-room school houses, required an investment of money, labor, knowledge, and skills of African American parents and teachers. Rosenwald grants also required county school boards to contribute to the total cost of school construction, maintain the buildings as part of the school system, and keep the school open at least a minimum number of months each year. School buildings had to be modeled on specific plans based on the number of teachers in the proposed building. The building’s orientation the placement of windows maximized light and minimized glare. Rosenwald funds required that schools have new desks and blackboards as well as two modern privies. The requirements were specific even down the color schemes on interior walls.

Building Shady Grove Rosenwald School

Shady Grove School was the sixth, and last, Rosenwald school constructed in Sumter County. The Nunn Industrial School, sometimes called the New Shady Grove School after the church on Hooks Mill Road, opened first in 1922. Mt. Zion school, southwest of Leslie, opened the following year. In 1924, three more Rosenwald schools opened: Gatewood school, next to Mt. Moriah Church on Mask Road; Plains School, on South Hudson Street; and Shipp Industrial School on Highway 49S. Shady Grove, the newest school, received its names from Old Shady Grove Baptist Church on New Era Road.

As with other rural Rosenwald schools in Sumter County, Shady Grove sat adjacent to a rural black church. Although a twentieth century building stands today, Shady Grove Baptist Church dates to the nineteenth century. In 1890, John R. McNeil, a white landowner, transferred slightly more than one acre to Joe Dowdell, Jackson Carter, and J. M. Littleton “for and in consideration of the love I have & bear for the Cause of Christ and the extension of his cause while on earth.”

Both Shady Grove Baptist Church and the McNeil family were influential in the establishment of a new school forty years later. The church already doubled as a school: in 1925, William L. Littleton taught at Shady Grove for $37 per month and Frankie M. Bowden for $25 per month. In November 1929, the Sumter County Board of Education voted “to contribute $500 to help build a Rosenwald school at Shady Grove” as soon as title to two-acres of land and “a subscription of $800 in labor and money is secured by friends and patrons of the school.” In February 1930, the school board secured the land through a series of transactions between themselves, Robert Duncan McNeil Sr., Shady Grove Baptist Church, and the Grand Lodge of the Grand Order of St. James.

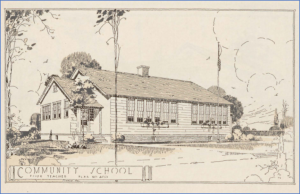

A Four-Teacher School. From Samuel L. Smith, Community School Plans, Bulletin No. 3 (Nashville: The Julius Rosenwald Fund, 1924), pg. 11.

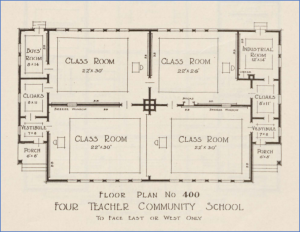

“Floor Plan No 400,” from Samuel L. Smith, Community School Plans, Bulletin No. 3 (Nashville: The Julius Rosenwald Fund, 1924), pg. 11.

Later that same year, the school board approved a bid by John W. Shiver to begin construction of the school. The Rosenwald Fund contributed $1,000, the school board contributed $500, and the local community raised the remainder of the total $1,839.25 cost. Over the next year, Shady Grove took shape on New Era Road. It was a four-teacher school designed to face east or west with four classrooms, two vestibules, two cloak rooms, and an “industrial room” for community use. While the plan made space for one restroom, funding requirements still called for two sanitary privies.

Shady Grove and the other five Rosenwald Schools opened on October 12, 1931, for a school term of six months. This was one month longer than for the 34 other black schools in Sumter County and this put the Rosenwald schools closer to parity with white schools. Shady Grove served the New Era Community as a public school for the next quarter of a century. There are still people in the county today who remember attending the school as children.

Shady Grove closed in the 1950s during a wave of building construction aimed at preserving the status quo of racial segregation by modernizing black schools. These new buildings, sometimes called “equalization schools,” continued the process of consolidating rural schools into a smaller number of larger schools that began a half-century earlier. Students who lived on New Era Road in 1950 had only a short walk to Shady Grove. A decade later, they traveled several miles to Northeast School on Upper River Road.

In February 1958, the Sumter County Board of Education prepared to sell thirteen schools made obsolete by rural consolidation into new, larger schools. At their next meeting, the school board accepted bids on twelve of the thirteen school buildings. The sale prices were only a fraction of the cost of purchasing and developing the land decades earlier. Marvin McNeill offered the board $150 for Shady Grove. Jimmy Carter moved to accept the bid and Hoke Smith seconded the motion. The land, and Shady Grove school, transferred back to the McNeil family.

The Preservation of Rosenwald Schools

Demographic changes in the 1940s, school consolidation in the 1950s, and desegregation in 1960s made Rosenwald Schools increasingly obsolete by 1970. In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Preservation put Rosenwald Schools on its list of the “11 Most Endangered Historic Places.” The National Trust estimates that only 10-12 percent of the original schools remain standing today. At Shady Grove, time has taken its toll. It is too dangerous to enter, but peering into the half-dozen openings, one can see that it has been used for storage of wood and, at least at one time, hay. In March 2007, the tornado that struck Americus damaged the roof; since then, the building has deteriorated at an ever-increasing pace. A large hole in the roof was not there two years go. When Shady Grove reaches its centennial, it is likely that the distinctive Rosenwald floor plans will no longer be visible.

Shady Grove is a monument to the perseverance against inequality and to an alliance between a northern Jewish philanthropist and a black educational leader. It is a reminder of the poor farmers, church members, and teachers who invested in this place to improve the lives of children. This place matters.

When we lose places that matter, history it not lost in a specific, quantifiable sense of the term. It is more akin to losing the power of sight and, eventually, speech. Without seeing Shady Grove, it becomes harder to ask the right questions when one drives down New Era Road. It is when we can no longer imagine the past, and therefore no longer ask the right questions, that we lose our history.