Part 3: An Americus lynching: The lost counternarrative

Published 11:48 am Wednesday, June 24, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Evan Kutzler

Vagrant. Drunk. Killer.

These images became central to the dominant white narrative in 1913 and remain so today. In 2018 and 2019, for instance, Sumter County Tourism featured the lynching of William Redding in ghost tours that trivialized this racial violence. Interpreting this event requires caution. We know nothing about events from Redding’s viewpoint and almost nothing about him beyond his name. His perspective on the initial encounter with Chief Barrow was lynched with him. On one level, the most important level, lynching rendered Redding’s actions irrelevant. Redding had no trial; therefore, he died an innocent man because in a society of laws he died unconvicted of any crime. Without an alternate accounting of specific events, though, the words of his killers are hard to unstick from the memory of the person.

The Confidential Letter

There was a counternarrative. On July 25, 1913, John M. Collum, the Principal of the Third District Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Georgia Southwestern State University), wrote to Booker T. Washington. Collum did not write everything he knew. He had information that, as he put it, “is not to be written on paper.” Yet he felt morally compelled to write something. “I have written you only as a matter of information; that I knowing, and that you may know the truth, and that knowing it, as bad as it is, we may make the most of it.” His courage to speak the truth had a clear limit. “So far as my name is concerned,” Collum wrote, “this is only a private letter.”

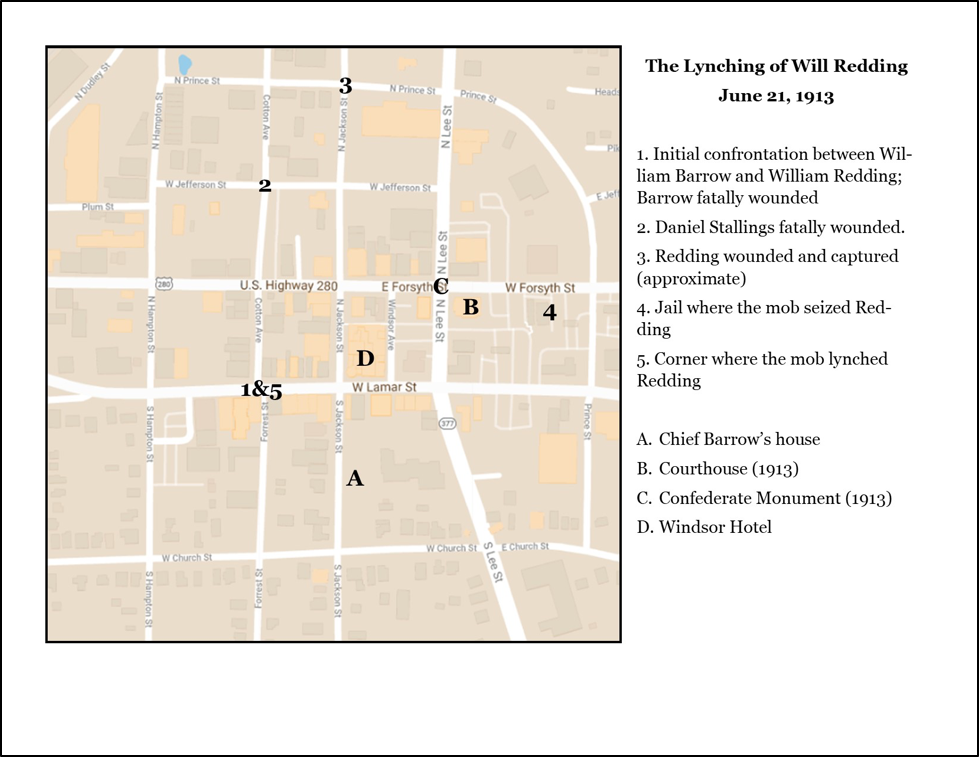

The principal was careful to distinguish between what he “could state as fact” and what he interpreted to be true. Collum’s accounting of the facts described Redding as neither drunk nor loitering. He was on a wagon, watching a mule team for an African American employer who had stepped into a store. “Chief Barrow ordered him to move the wagon,” Collom wrote. Redding “explained to him that the owner would take charge of it at once and move it.” When Redding got off the wagon to get the owner, Barrow and two white men grabbed him in a scene reminiscent of the pool hall raids on the same street nine months earlier. “There was resistance and a struggle, and, possibly, the prisoner was struck several times.”

During the three-on-one struggle, Barrow drew his gun on Redding. This is where the account, like the dominant narrative, turned hazy. Redding somehow overpowered three white men, grabbed the officer’s gun, and shot Barrow as he fled. It is likely that the armed men accompanying Barrow, in trying to shoot Redding, took Daniel Stallings down instead.

The Unlikely Informant

No single account can represent the whole story. On the one hand, Collum was an unlikely informant. He had been a white politician in an era of increasing black disenfranchisement. Collum also owned a plantation in Schley County and profited from the labor of sharecroppers. He prided himself on maintaining a peaceful, if unequal, status quo. “We employ many colored people on our plantations,” Collum told Washington. “We have never had one brought before the courts.” He led segregated schools for fourteen years before becoming principal of the college in Americus. He also worried that times were changing. Sharecroppers had become more difficult to control than in a previous generation.

On the other hand, individuality matters. Collum was a planter, a politician, and the leader of segregated schools, but the South has never been a monolith and white southerners were not all cut from the same cloth. Born in 1857, Collum came from a small farming household that owned a little land and enslaved no one. His father, thirty-six years old when Georgia seceded from the Union, could not have fought in the Confederate army because he was a disabled veteran—an amputee—of the Mexican-American War. The Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy rose to prominence during Collum’s adulthood. Collum likely sympathized with white southern memories of the Civil War, but he and his siblings were technically ineligible for membership in those organizations.

An article by Washington in the Atlanta Constitution had prompted Collum’s letter. The article pointed out the year-to-year reduction in lynching victims in the early months of 1912 and 1913. Washington inferred from these numbers “a growing regard for law and order,” but he also admitted that two “exceedingly barbarous and inhuman” murders had taken place in Georgia. Summarizing the Times-Recorder account, Washington alluded to the death of William Redding without saying his name: a man dragged through the streets, beaten with a crowbar, hung to an electric lamppost, and shot 1,000 times in front of at least hundreds of participants. Washington added one detail that had not appeared in the newspaper coverage: the killers, before burning Redding’s body in the street, had boiled him in oil.

Collum offered no corrections to Washington’s summary. “While many good people here abhor the disgraceful act,” he wrote, “from after happenings it must be concluded that the lynchers have terrorized the whole people, or that a vast majority is in sympathy with the mob.” Collum also added crucial details. The Times Recorder stated that one reverend attempted to intervene. In Collum’s account, three reverends entered the jail: James B. Lawrence of Calvary Episcopal Church, Robert L. Bivins, pastor of Furlow Lawn Baptist Church, and J. W. Stokes. The men in the mob forcibly removed Lawrence from the building. Bivins followed the mob and pleaded with them not to burn Redding’s body. Men from the mob threatened him, “If you don’t leave we will burn you.”

A Fuller Narrative

A lot transpired between the lynching in June and Collum’s letter to Washington in July. William Barrow and Daniel Stallings had died of their wounds. The local court system had also concluded its meager investigation. The editor of the Times-Recorder, while stating “that society is fortunate to get rid of [Redding] and his kind,” called on Judge Zera A. Littlejohn to “call an extra session of the grand jury for the county” to investigate the lynching. As historian Mark Ellis has demonstrated, this was nothing new for Judge Littlejohn. He often pleaded unsuccessfully for grand juries in southwestern Georgia to bring charges against lynchers.

The all-white, all-male grand jury was never likely to bring charges against their friends, neighbors, and family members. That there was no secrecy made the outcome even more certain. The names of the twenty-three grand jurors were not only recorded by the court but also published in the local paper. Frank P. Harrold, one of the grand jurors, kept a handwritten list of the witnesses. This also likely mirrored a partial suspect list.

Harrold drafted the grand jury’s report. It excoriated local law enforcement and local citizens. After examining more than 150 people, the grand jury concluded that the police “have failed utterly to give us the names of the mob.” The other witnesses “gave us a great deal of the vaguest kind of testimony, none of which was strong enough to fix responsibility of the lynching on any particular person or persons.” One thing was clear. The police made no attempt to protect Redding. “We have labored earnestly for days in this matter,” they concluded, “and are satisfied that if we had had the cooperation of the public at large in our deliberation, the result would have been different.”

Collum sympathized with the grand jurors who were thwarted not only by evasive witnesses but also a broader conspiracy. Collum speculated that “another court official entrusted with drawing the bill,” likely Solicitor General James R. Williams Sr., stood in the way of the grand jury. It was also an open secret, Collum asserted, that local police and military organizations aided in the lynching. “The whole city knew [the mob] was being formed,” Collum wrote. Policemen arrested women “for being on the streets, and yet they stood about in pairs remoter from the lynching.” The local military company supposedly restored order at 10:00 p.m. However, those same soldiers, “with arms furnished by the government, had contributed more than the average number of shots fired by the lynchers in riddling the body with bullets.”

Collum’s letter provides an essential, missing perspective on the lynching and its aftermath. Yet he was no hero—no Atticus Finch. Collum believed he knew the truth about what happened in Americus, but he could only speak it on the condition of confidentiality. In 1913, white supremacy meant the power to destroy William Redding without legal repercussions. It also meant to the power to compel silence and control the narrative. We must be careful not to perpetuate that narrative.

Part 4 of this series will appear next week.