“Dear Santa” in a year of war and pestilence

Published 9:07 am Wednesday, December 2, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Evan A. Kutzler

November 28, 2020

evan.kutzler@gsw.edu

On December 6, 1918, the Americus Times-Recorder printed a letter to Santa Claus written by six-year-old Charles Walker. The boy asked Santa for a bicycle, toy sand mill, and a stocking full of “good things to eat.” His list also included a uniform and a machine gun on a turret, probably because his older brother Henry was a soldier in the U.S. army. The military discharged Henry the same day Charles’s letter to Santa appeared in the newspaper.

More children from the Walker household at 814 South Lee street wrote Santa letters that year. Nine-year-old Frances asked for a bicycle, a full stocking, and a horn. She also requested explosives, albeit only in the form of sparklers and firecrackers. Eugenia, a sixth-grader and the oldest Walker child to write Santa in 1918, asked for the same small items as well as a coin purse, skates, and—in a rare mention of a brand-name—a Kodak. She was one of several sixth graders to ask for a camera that year.

Writing letters to Santa was a useful diversion for children and adults during the tumultuous Christmas season of 1918. When the Great War ended on November 11, 1918, more than 116,000 U.S. servicemen had died. Meanwhile, a deadly influenza pandemic spread around the world, ultimately killing about 675,000 Americans and approximately 50,000,000 people worldwide. In Richland, this included Annie Lee Gordy Webb, Lillian Gordy’s older sister. Six years before Lillian gave birth to her oldest son, Jimmy Carter, the experience of caring for her dying sister influenced her to become a nurse. Children and young adults were especially susceptible to the flu, making it a scary disease for families like the Walkers, the Webbs, and the Gordys.

Publishing Dear Santa Letters

The Walkers were not alone in writing letters. White children (and adults writing under a child’s name) wrote more than 200 letters to Santa that year. Six days before Thanksgiving, the Times Recorder printed a letter from Argyle Crockett, who lived across the street from the Walkers. Argyle asked for a sand mill, fireworks, and matches. He kept the list short because he knew that Santa had “to give so much to the Belgian and French children.” He must have understood that Santa had some catching up to do after the war.

When the Times Recorder published Argyle’s letter, the editor called for more letters. Santa had requested it. “The editor of The Times-Recorder has received a letter from Santa Claus, asking him to receive letters form children to Santa Claus sent in care of the Times-Recorder,” the editor reported. “All letters thus received will be forwarded to Santa Claus, and some of these letter[s] will be published. Send your letters, boys and girls, to “SANTA CLAUS, care Times-Recorder, Americus.”

Santa’s request was not unusual. In the preceding fifty years, U.S. newspapers began to collect and publish children’s letters to Santa or, sometimes, from Santa. The price of sending letters had dropped during the Civil War era and mail carriers began delivering to home addresses around the same time. “The use of the post office to contact St. Nick began as a particularly American phenomenon,” Alex Palmer writes in the Smithsonian Magazine. “Scottish children would shout their wishes up the chimney, while Europeans simply left out stockings or shoes for the gift bringer.” The Times-Recorder began publishing local Santa letters in 1913. The sheer number of Dear Santa letters published in 1918—10x more than any other year that decade—added to an unusual year marked by war and pestilence.

Writing Hopes (and Anxieties)

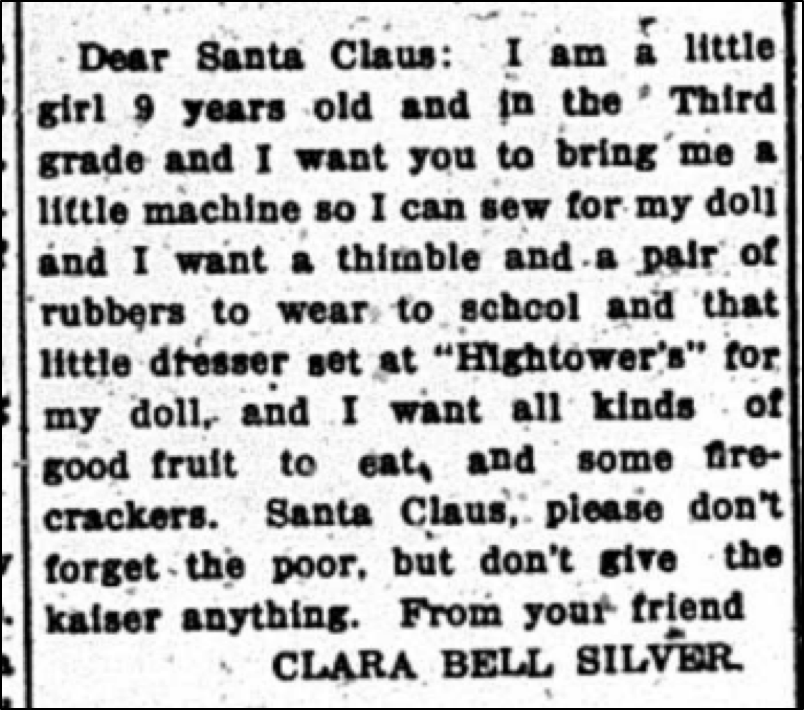

Requests that linked the Walker children echoed in other letters as well. Children asked for stockings with fruit and candy. They asked for toys from dolls, automobiles, and airplanes to scooters, bicycles, uniforms, and guns. Earl Andrews and Clara Bell Silver, two third-graders, asked for furniture from the Hightower Bookstore (present-day Café Campesino). Dolls whose eyes opened and closed were also in high demand. Four-year-old Florence Speer at 211 Cherry Street was in good company when she asked for “a big go-to-sleep doll.” Other children called them “sleepy dolls.”

Adults encouraged the young writers to think beyond themselves in making their Christmas lists. Argyle Crockett was not alone when he reminded Santa not to forget the children of U.S. allies in Europe. In fact, Americus boys and girls mentioned Belgian and/or French children more often than anyone else in their letters. This reflected a specific World War I era socialization. War made the front pages for years. By 1918, Americus children were as familiar with depictions of hungry French and Belgian children as they were with German atrocities. Cobb resident Clara Bell Silver likely shared the sentiment of many children (and adults) when she asked Santa to remember the poor, “but don’t give the kaiser anything.”

Aspirants of Santa’s goodwill also drew attention to local needs. Dozens asked Santa to look after orphans and the poor. Children also enclosed money in 1918 as they had done since the Times-Recorder started collecting letters. Sam Jr. and Tom Heys on Taylor Street were among the several dozen children who enclosed dimes and quarters for an “Empty Stocking Fund.” After collecting the money, the Times-Recorder turned it over to a local group who distributed toys and food to poor families. While it was not stated exactly who the Empty Stocking Fund supported, the demographics of the letter writers is clear. Letters published in the Times-Recorder tended to come from middle- and upper-class white families. In that way, the published Santa letters show an imprint of a segregated era.

The epidemic of 1918 affected letter writing as well. When cases of influenza and pneumonia rose in October 1918, schools, churches, and most businesses closed for weeks. The city government called on residents to wear gauze masks in public and recommended wearing them at home as well. The new city hospital, located just 500 feet away from the Walker household’s front door, held sick patients. At least two neighbors within five blocks of the Walker house died of the flu.

References to the flu left an eerie but useful reminder that childhoods in the past were not simpler or carefree. Someone who did not sign their name asked Santa whether he had come down with the flu. “I hope not,” the letter went on, “for it might make you sick to be out in the night air on December 24.” After asking for a 29-inch doll bed, Eugenia Bragg’s letter served as a precautionary note for his visit to 301 Taylor Street. “And Santa,” she wrote, “please don’t forget the flu at my home. Evelyn and Louise and Verna and mamma all have the flu. Santa, I hope you won’t take the flu.” Eugenia did not yet know that her family would survive. Family health, and Santa’s health, were important concerns for hopeful children.

Some children hoped that Santa might cheer up the sick. From her family’s farm on Bonds Trail road, Laura Merle Morrell asked Santa not to forget Dewey Hicks, a pilot trainee at Souther Field. “He is in the hospital sick with the influenza,” she told Santa. Dewey Hicks survived; however, Bernard Hicks, a member of Dewey’s barracks, and three other airmen died the next day. Other children lowered their expectations that year. Grace and Raymond Collins at 413 Barlow Street kept their lists short. Whoever wrote on behalf of two-year-old Raymond told Santa, “I am not going to ask for much for my daddy has had the flu.”

Rereading Santa Letters

Wearing a mask and scrolling through a microfilmed copy of the Americus Times-Recorder, I was not looking for Santa letters when the headlines caught my eye. What first seemed trivial then looked remarkable when it became clear that the newspaper received—and published—so many more letters in 1918 than other years that decade.

Santa letters reflect the observations of historians of childhood. The term itself, “childhood,” is a contested one. Adults have disagreed for a long time about who children are, and what they need to become adults. The history of childhood is one of invention and tradition, change and continuity. The child who wrote to Santa in 1918 may have had parents and grandparents who once wrote to Santa. Their great-grandparents had almost certainly not written to Santa. The tradition also reflected changes in commercial culture and the idea that children made up a specific demographic with unique consumer tastes. Letters that once focused on small, practical items in the late-nineteenth century increasingly identified specific store-bought products in the twentieth century.

The letters also show children as active participants, not just passive observers, in a season of worry. Children in Americus wrote to Santa in 1918 with the expectation that reasonable requests would be granted on Christmas morning. There is every reason to believe that they were rewarded. In the process, they left a window into the local and global concerns of children in a complicated season.

The 1918 “Dear Santa” letters, with a name index, can be found here: http://evankutzler.com/publichistory/dearsanta/