Alf Hudson, Perry Grove, and the Middle Passage

Published 3:09 pm Wednesday, August 11, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BY: Evan A. Kutzler

On July 11, 1920, Lucius Hudson laid Alf Hudson to rest at the Old Perry Grove Baptist Church, a stone’s throw from Chokee Creek in southeastern Sumter County, Georgia. The burial involved no undertaker and neither of the two Hudson men left much of a traditional historical record. Lucius, aged 40 and recently widowed, lived alone and worked as a tenant farmer across the Lee County line along the Leslie-Leesburg Road. It was Lucius who reported the death of Alf—”old age” he said—to health authorities. Alf was about 75 years old and still performed light work on a farm near De Soto. Lucius did not know the name of Alf’s mother or father, but he knew two important details. Alf Hudson was born about 1845 in Africa.

This was unusual for a death certificate in 1920. Most African Americans who became free in the 1860s had families in North America for generations. The grandparents of a freedperson’s grandparents were often here long before the American Revolution. Some men and women born into slavery in the antebellum period knew parents and grandparents who had survived the Middle Passage. In 1850, Zorah Hayslip, a white man, identified the ages and sexes of six people he held in slavery in southeastern Sumter County. A seventh person, born about 1790 in Africa, had died in April that year of an unnamed “chronic disease.” Five of the younger adult men and women could have been her children. The oldest man may have been her husband.

Alf Hudson was among a small number of African Americans in this region who survived the Middle Passage and became free in their lifetime. Calling the names of these individuals acknowledges an echo of the middle passage that could be heard long after the United States formally outlawed the importation of enslaved people in 1808. The current national reckoning with race and slavery reminds us that the 156 years between 1865 and 2021 is not so long after all. There was only a 57-year gap between 1808 and 1865.

US Census records inadvertently offer the most complete accounting of freedpeople who survived the Middle Passage. In 1870, 319 Black Georgians—or 6 per 10,000—reported Africa as their birthplace to census workers. Only 129 men and women—2 per 10,000—did so a decade later. “Unless it was a symbolic political statement, there was no motive to misrepresent where you or a member of your family was born,” historian David Dangerfield tells me. “These are probably survivors of the Middle Passage.”

Black Sumter County respondents exceeded the Georgia average both years. In 1870, James Morgan, Selon Black, Harry Rees, Hagar Thomas, George African, Thomas Wells, and William Nelson said they were born in Africa. In 1880, Cymons Wood, Rochel Wood, Cyrus Fuller, and Frank Stuart told a census worker the same thing. Alf Hudson did not appear in these census records at all, and the men in 1870 did not appear in the 1880 census, suggesting that census records may undercount the true number. Even the best historical records are fragmentary and incomplete.

The Black men and women who reported African births here left few additional clues about their lived experiences. While the life expectancy of an enslaved person was in the 20s or 30s (estimates vary), James Morgan, Selon Black, Harry Rees, Thomas Hagar, and William Nelson lived long lives. Infant and child mortality is the most important factor in estimated life expectancy. People who survived childhood sometimes lived long lives. For the men who reported being born in Africa in 1870, their median age was 101. In other words, most were born decades before the end of the slave trade. A few of the older men still worked. Harry Rees, born in 1800, still worked as a farm laborer seventy years later. James Morgan, born about 1790, could not read and write in 1870, but he worked at the Sumter Republican.

The men and women who reported African births in 1880 hint at more than just longevity amid the harsh conditions of slavery. The median age fell to 62.5 meaning that most were born well after the official end of US involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. This is a reminder that despite the United States’ ban on the slave trade after 1808, an illicit trade continued right up to the Civil War. Slave traders probably smuggled Cymons and Rochel Wood, Cyrus Fuller, Frank Stuart, George African, and Thomas Wells into the United States.

Alf Hudson may have had a similar journey that took him to southwest Georgia. It is a long way from Perry Grove in Sumter County, Georgia, to the mouth of the Congo River, but the two are connected both by water, history, and the forced movement of people. In 1860, the waterway still went by its longer name, Chokeefichickee, a Muscogee word that may have meant, “rotunda raised on a mound.” From its headwaters near Perry Grove, it flows south and then east past the railroad towns of Leslie and De Soto before turning sharply south, crossing into Lee county, and emptying into the Flint River. In the early nineteenth century, landings on the Flint River provided navigable waterways south toward the Chattahoochee River and the Gulf of Mexico or north toward Oglethorpe and Montezuma.

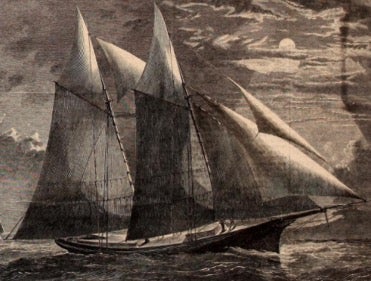

Chokee Creek cut through cotton plantations in the 1840s and 50s. Its drainage basin included at least 600 acres of John Basil Lamar’s 3,000-acre estate in Sumter County. Lamar was a member of an elite political family that included his brother-in-law Howell Cobb and his cousin Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar. The latter became infamous for enslaving 409 Black people from the Congo River in West Central Africa and landing the slave ship, Wanderer, on Jekyll Island in 1858. Courts never convicted Charles Lamar of violating U.S. laws that, on paper, equated the international slave trade with piracy. Lamar flouted the hangman’s noose when he brazenly committed a capital offense.

The slave traders who abetted Lamar spread out from Jekyll Island across the South. Authorities briefly stopped Richard Aiken, who became one of the acquitted co-conspirators, in Worth County, Georgia, with a wagon train and 36 Africans. According to historian Tom Wells, newspapers reported sightings of Africans from the Wanderer in every state in the lower South. “Twenty were allegedly found on a Colorado River plantation in Texas,” Wells writes. “[Nathan] Bedford Forrest’s slave-trading company in Memphis was supposed to have six offered for sale.” All of this took place 50 years after the United States ended the slave trade. It is a reminder, Dangerfield says, of the “ideological and economic interest in preserving slavery—even reopening the slave trade—right up to the Civil War.”

Old Perry Grove Baptist Church in the late-nineteenth century and stood in its original location until the mid-twentieth century. Perry Grove looked like a typical southern church: a wooden, rectangular building with a front-gabled roof and either a porch in the front or a small rectory in the back. As Deacon Aaron Johnson explains, Perry Grove had an informal agreement with the (White) Bone family rather than formal title to the land. The relationship soured and the landowner forced the church to move.

The cemetery is all that remains of the original church when the congregation relocated to a new building closer to Leslie. Years of farming right up to the ambiguous cemetery boundary —first by the Bone family and now by a company owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—has been destructive. Some marked graves have been lost over the years. Other early graves are decorated with single, uninscribed stones. The wide spacing of marked graves hints at the many now-unidentifiable ones. Alf Hudson is somewhere in this cemetery.

Alf Hudson’s death certificate is the only known documentation of his life. Historical fragments, such as this one, are broken pieces of human stories. They cannot always be made whole again. I can speculate that Lucius was Alf Hudson’s son, but I cannot even be sure of the relationship between the two men. Nor can I conclude with any certainty that Alf Hudson arrived on The Wanderer or was enslaved by the Lamar family, but the dates and circumstances prompt the question. And we should ask the question even if we cannot answer it. The historical imagination is sometimes bigger than the historical record itself. Yet there is a benefit to calling his name and acknowledging what we know—and what I don’t know—about how Alf Hudson’s story connects to Chokee Creek, the Atlantic, and beyond.