Saving Places, Telling Stories

Published 4:10 pm Tuesday, March 1, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Evan Kutzler

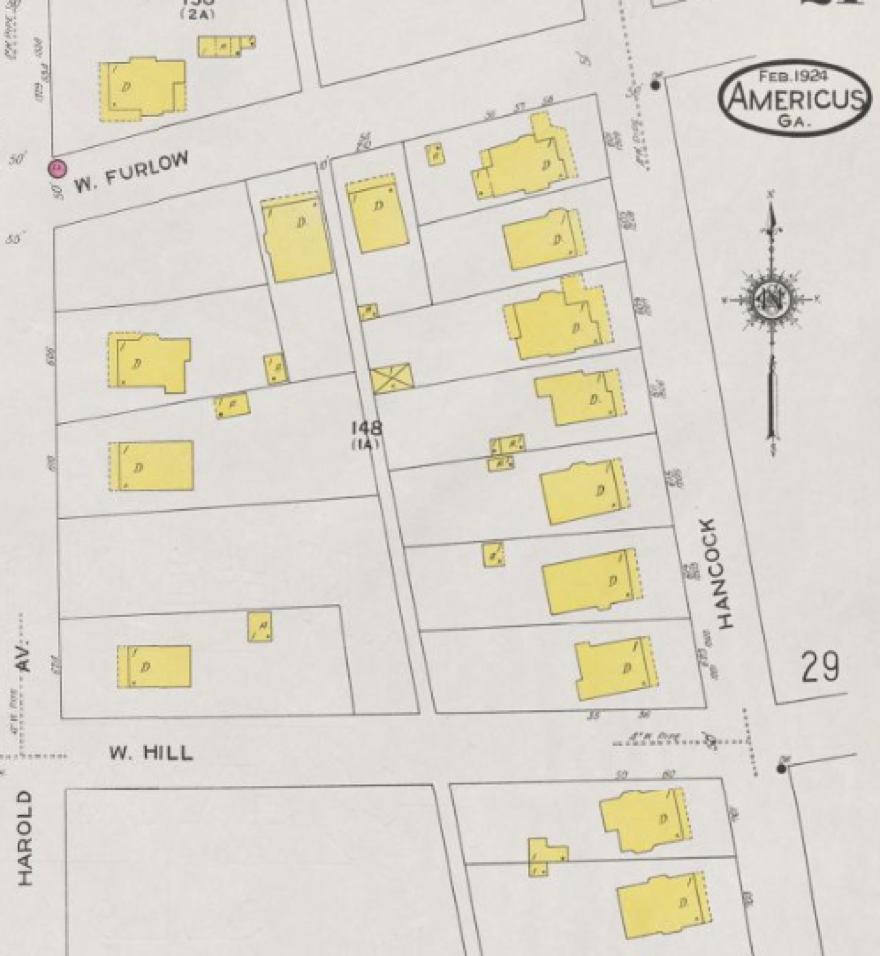

Hancock Drive in Americus has a medley of historic homes. A walk along this street will reveal neither a time capsule of one era nor a perfect timeline of building patterns over the years. House types and styles, in general though, become newer as one travels south from the 1850s Gothic Revival home at the corner of College and Hancock. Bungalow and Craftsman houses from the 1910s and 20s replace Queen Anne Cottages and then fade; one-story American Small Houses and a few two-story Colonial Revival houses predominate on several blocks. Then Cold War era ranch houses mark the street’s southern terminus at Daniel Street. Somewhere along the way one crosses the nominal line separating the historic district from the rest of the neighborhood. But this is a zoning technicality.

There have been subtle changes in recent years. Fewer homes are for sale and several have undergone significant rehabilitation. As a type of property management, rehabilitation stands out. Other strategies include preservation, where a property is stabilized and protected from deterioration. Nothing is added; nothing is removed. All of the previous layers of a property are treated as important. Restoration, more destructive than preservation, removes some layers to reflect a specific period in the property’s history. For example, Jimmy Carter’s boyhood home in Archery has been “restored” to its 1930s appearance. Historic properties, like most of Colonial Williamsburg, can also be reconstructed using historically appropriate materials and methods to recreate the impression of authenticity. There are benefits and consequences to each strategy.

A rehabilitation modernizes an historic property to meet the needs of the present. It is practical rather than idealistic. Turning commercial buildings into apartments, putting shops in an old warehouse, or fixing up an old house are all possible rehabilitation projects. Best practices call for minimizing damage to historic fabric. Repair damaged materials instead of replacing them. Avoid harsh chemical treatments. Stay away from adding conjectural features from other properties. Yet rehabilitation is flexible. It “preserves history” by maintaining a sense of connection to the past while enabling properties to evolve to meet present and future needs.

Recent work on two properties—601 and 701 Hancock Drive—offer two examples of local rehabilitation projects. The former house is undergoing nothing short of a full rehabilitation: a new roof, HVAC system, electrical wiring, porch work, and interior painting. Work on the latter house is subtler from the street view, but the interior kitchen and bathroom work alone has transformed this house. Both houses contribute to the Americus Historic District and hold stories about Americus and its history.

The Schneider and the Glanz Houses

Houses help us tell myriad stories about our city’s past. The house at 601 Hancock Drive, built for Claude and Leila Schneider in 1908, was one of several Schneider homes in the city. In 1912, Claude’s brother, Edward Everett Schneider, and his sister-in-law, Pearl, moved in across the street. Both Schneider brothers were the grandchildren of German immigrants to the United States and the family owned the Schneider Marble Company in Americus. The family’s name appears as the maker’s inscription on many early twentieth century headstones in Oak Grove and Eastview cemeteries. The company also built the Chehaw Memorial for the Daughters of the American Revolution installed near Leesburg, Georgia. Claude, the eldest son, likely worked for the family business at some point. His career as a traveling salesman took the family to Macon.

The construction of the Claude and Leila Schneider home, a Queen Anne Cottage in layout with classical ornamentation, is unusually well documented for a residential house. In December 1908, a reporter from the Americus Times-Recorder walked through the house just as construction ended. “To the right of the reception hall, which has a large fire place with handsome equipment, are the parlor, two large bed rooms and the bath room,” the Times-Recorder reported. “A long rear hall, extending from the main hall to the rear of the house separates these rooms from the dining room, pantry and kitchen.” The house’s distinctive rounded porch drew attention with its ornamented columns and a porte cochere (“coach door”) for a carriage—or perhaps a Model T Ford that came out the same year. The journalist predicted the house would be “one of the many tasteful monuments” of its contractor, George C. Hall.

The eccentric contractor who built the Schneider house on Hancock Drive was more colorful than the Schneider family. George C. Hall’s reputation went up like a rocket in 1908 in this city. Within a few years it came down like a stick. In the spring of 1908, the Times-Recorder regularly ran testimonials from prominent residents about Hall and his foreman, D. G. Hagin. “The cottage which Contractor G. C. Hall recently completed for us, we are pleased to state, is satisfactory in every respect,” one customer wrote. “The work was done with care and dispatch, and we heartily recommend him to anyone desiring to build.” Hall’s advertisements carried his slogan: “Do it right, and do it now.”

Hall’s problems had nothing to do with the quality of his residential and commercial building projects. No one publicly criticized his workmanship. The issue had more to do with Hall’s gambling at the racetrack. In 1908, he owned three horses, including “True Tucker” and “Happy Bob.” Hall’s fortune plummeted and he lost ownership of both horses within a month of finishing the Schneider house. He filed for bankruptcy and later faced federal charges for perjury and concealing assets. He spent 60 days in jail.

The journalist who praised Hall also foresaw the rapid expansion of Hancock. This was not a risky prediction. After all, the Schneider home was the fourth house built on Hancock that year and construction steadily moved south. In September 1912, William Worthy and Fabian Beavers announced plans to build a bungalow house at the southwest corner of Hancock and Hill. An earlier house stood in the same location until a fire destroyed it in 1901. This previous house was one of only five homes on the street dating to the nineteenth century.

The bungalow built for Worthy and Beavers—neither of the two men were professional builders—received far less attention in the local newspaper. Yet this house reveals the changing patterns of homebuilding in twentieth-century Americus. The house’s bungalow form, like so many nearby houses, marked a turn away from the Queen Anne cottage that was still lauded in the newspaper a decade earlier.

The people who lived in these houses also remind us of the itinerant nature and global connections of residents in a southern city on the move in the early twentieth century. Households on Hancock in the 1916 city directory were predominantly owned or rented by the families of a professional class: commercial travelers, salesmen, a railroad engineer, and a conductor. Nathan and Sarah Glanz, who lived at 701 Hancock in 1916 with Rohoma, Emanuel, Aminado, and Joseph, exemplified this pattern with an exceptional twist: all six Glanzes were born in Russia between 1872 and 1906. Nathan Glanz, a salesman in the button industry, came first to the United States. When he applied for citizenship in 1913, Sarah and the rest of the family lived in Jaffa, Palestine. The Jewish family called many places home, including Macon, Chattanooga, and Queens, in the United States. Yet Americus may have been one of the first places the Glanzes lived as a family in the United States.

Rehabilitations and the Historical Imagination

Historic cities, streets, and houses have multiple layers of history. The Glanz and Schneider families, the contractors, and the unnamed workers who did most of the construction offer limited glimpses into complicated pasts. Some stories are easier to excavate than others. The house at 601 Hancock Drive still casts an aura of grandeur that the rehabilitation is beginning to bring back. The interior trim, the curved porch, and even the hexagonal paving stones sets this house apart on the block. The simple, sturdy bungalow at 701 Hancock does not easily give up its important story about Jewish immigrants. In fact, if not for a breadcrumb in the 1916 city directory, it would have been difficult to rediscover the house’s global connections.

Studying history helps one to ask important questions about the past and the present. The skills that train critical thinkers, shrewd planners, and good leaders also enrich those same lives by stirring historical imaginations in everyday life. Historic preservation through good rehabilitation facilitates this humanistic endeavor by allowing one to imagine these connections between place, space, and time. A good historic rehabilitation strikes the balance between the old and new, allowing an historic property to become viable in the present and future while saving what makes it matter in the first place.