The Layers of a St. Patrick’s Day Postcard

Published 7:31 am Thursday, March 17, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Evan Kutzler

On March 17, 1910, “H” mailed a postcard to Loretta Hennessy in Macon, Georgia. The message section contained the following poem: “Holy Moses, what do you think / St. Patrick’s Day and not one drink. / I know when I die, He’ll turn me down / for not doing better in Americus town.” While the sender left us only an initial, the recipient lived in a Catholic household with Irish and German heritage. Loretta’s ancestors had been part of a German Roman Catholic community in Pennsylvania. Her husband came from Canada, but his parents arrived from Ireland with millions of other immigrants in the nineteenth century.

Postcards can offer critical thinking exercises. What’s the historical value in a common postcard? Perhaps the image captures something about a city, a business, or an individual. Maybe the handwritten message provokes questions about an event, experience, or pattern in the past. A social or cultural historian may ask different questions than a political or military historian. This simple artifact offers a portal into the many dimensions of studying history.

The Modern City

Postcards grew in popularity in the early twentieth century. Beginning on March 1, 1907, the United States Postal Service allowed postcards to have a full-size image on one side and a “divided back” on the other with designated space for a message and an address. During the next fiscal year, the postal service carried at least 677,000,000 postcards—an average of seven-and-a-half postcards per person living in the United States at the time. Postcards were part of social media in the early twentieth century.

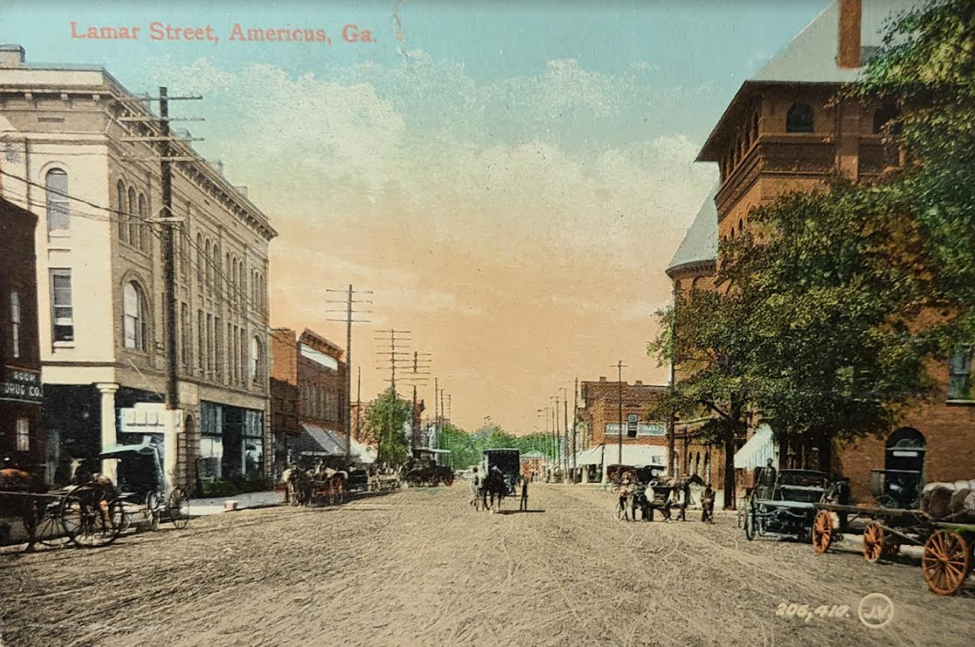

Colorized postcards aided city boosters who used these images to elevate the public reputation of their cities and draw in business and travelers. This image depicts Lamar Street with telephone poles towering over horse- and mule-drawn carriages. The Windsor Hotel, the Allison building, and Holliday’s Bookstore are all visible. Now an image of “historic” Americus, these buildings were all new when the photograph was taken. The Windsor Hotel was less than 20 years old and Allison Building was only about three years old. This was one of many images of “New South” Americus circulating at the start of that century.

St. Patrick’s Day

St. Patrick’s Day, as a secular, Irish-themed day of revelry, goes back in some U.S. cities to the colonial era. It became even more popular amid waves of Irish immigration to the United States. While the vast majority of these newcomers settled in northern and midwestern cities, the Irish moved to southern states too. Cornelius and Mary Coffee, both in their mid-twenties and born in Ireland, owned a small farm near Americus in 1860. Jeremiah Sullivan, John Duke, and John Callahan, all slightly younger, lived in the same all-Irish household in Americus. Other Irish-born Americus  residents included Daniel and Mary Coffee, Michael Hanlon, Michal Foley, Morris Butler, Thomas Charran, William May, and J. Ellis.

residents included Daniel and Mary Coffee, Michael Hanlon, Michal Foley, Morris Butler, Thomas Charran, William May, and J. Ellis.

Irish-Americans fought in both the United States and rebel armies during the Civil War, and Camp Sumter became a place where thousands of Irish-Americans lived and died as prisoners of war. Frederic Augustus James, born in East Boston, kept a poem titled “St. Patrick’s Day” at Andersonville in his diary. He arrived in Georgia after St. Patrick’s Day, and he may have copied the poem from another prisoner. The message focuses on the visceral conditions of the prison but ends on a message of hope: “This is Patrick’s Day; with stout hearts let us stand / We’ll keep our spirits up while in this region of the damned / We’ll place our trust in Providence whilst with grim death we cope / ‘Dum spiro spero’ while there is life there’s hope.” James died at Camp Sumter in September 1864 and is buried at grave 8858 in Andersonville National Cemetery.

Americus newspapers paid little attention to St. Patrick’s Day until the twentieth century. In 1910, St. Patrick’s Day overlapped with “Bonnet Day” (held in the lead up to Easter) and the white-only Democratic primary. “This is St. Patrick’s Day,” The newspaper reported, “and all patriotic Americus will adjust her bonnet; carefully avoid the snakes, and vote early.” H’s poem, taken at face value, raises more questions than answers. Not a single drink—on St. Patrick’s Day?

Prohibition in Americus

The context of prohibition offers some answers. While a nationwide ban on alcohol lasted from 1920 until 1933, Georgia’s prohibition began 13 years earlier and lasted several years longer. In fact, the Empire State had a long history of dipsophobia (fear of drinking alcohol). In Trustee Georgia (1732-1752), the colony’s leaders forbade strong liquor from 1735 until 1742. Temperance activists gained steam again in the late-nineteenth century with a sales ban on election days and increased liquor taxes. At the urging of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, an 1885 law allowed counties to vote to forbid most alcohol sales. This led to an urban-rural divide in Georgia, with many rural counties going “dry” and many cities staying “wet.” To the thirsty envy of some in surrounding counties, Americus had between 30 and 40 saloons in 1900.

The city’s saloon era did not last. State and national activism set the long-term context, and the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 served as one of the short-term triggers. White animosity toward a growing Black middle class, combined with racist assertions about drunkenness and rape, led white mobs to attack African Americans and Black businesses. In the end, two whites and between 25 and 45 African Americans died in the riots. The political climate became ripe for statewide prohibition the following year.

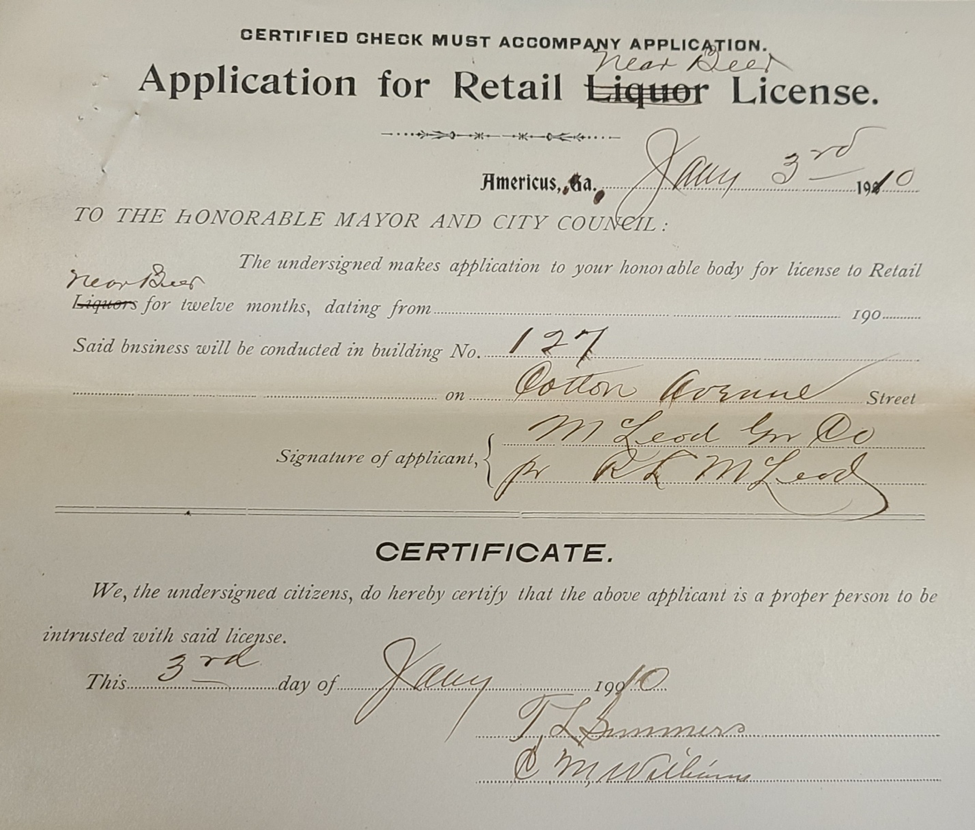

Statewide prohibition did not entirely prevent legal—let alone illegal—alcohol production, transportation, and sale. The 1907 law had special loopholes. There was an exception for “private locker clubs” that catered to wealthy Georgians. The law also permitted low-alcohol “near beer” sales and this set off a debate about how “near” these beverages were to beer. “The state has become flooded with ‘near beers,’ some of which are so near that the confirmed old toper cannot tell the difference,” a frustrated pro-temperance representative asserted. “The prohibition law was intended to prevent the sale of all drinks which had any alcohol in them at all.” Applications for near beer licenses indicate that there was alcohol in Americus. The challenge for H was that St. Patrick’s Day fell on the Democratic primary and laws forbid even near-beer on election days.

Prohibition laws in Georgia soon tightened and, then, loosened over the course of several generations. The state ratified the Eighteenth Amendment that prohibited alcohol in the United States in the summer of 1918 and never ratified the Twenty-first Amendment repealing it. Even after Georgia repealed state prohibition in 1935, local “blue laws” stayed in effect for decades. In the spring of 1939, a referendum on repealing prohibition in Sumter County tied with exactly 610 votes in favor and 610 votes against. Finally, the cork came off. It started with wine in 1941, but one could not legally buy beer or liquor in local stores until 1958. Beer became legal by the glass in 1960. Mixed drinks in restaurants were not allowed until 1985.

Pint in Hand?

While neither state nor national prohibition laws stopped people from drinking, finding a legal beer on an election day, even if St. Patrick’s Day, was difficult in 1910. Or was it? Could H have written the silly poem tongue in cheek—or pint in hand? Look at the handwriting again. In this interpretation, the postcard flaunts state and local prohibition laws. One can imagine both sender and recipient chuckling at the thought of “drunk mailing” an unsealed message like this one. Perhaps it was wise to sign with only an initial.

Unless DNA technology comes along to let us know the name and blood alcohol content of the person who licked one-cent Benjamin Franklin (a moderate drinker who published The Drinker’s Dictionary in 1737) stamp, we will never get much closer to knowing the identity or the sobriety of the writer. It also does not really matter. More important are the questions this postcard raises about the city, its people, its holidays, its laws and the change and continuity in its history over the past century. These at-times divergent and at-times convergent paths lead to new puzzles and new questions that are all fair game in studying the past.

The St. Patrick’s Day postcard, small as it is, should be where people can see it. It will be donated to Pat’s Place in exchange for a pitcher of beer—and not near beer.