Influenza in Americus Part 3: Remembering a Pandemic

Published 7:16 am Thursday, May 12, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BY: Evan Kutzler

Five years before marrying Earl Carter and six years before giving birth a son named Jimmy, Lillian Gordy became a caregiver. Her sister, Annie, as well as her brother-in-law, Jay, came down with influenza while expecting their first baby. Jay survived, but the disease killed both Annie and her unborn child. It was a tragedy repeated over and over during the influenza pandemic of 1918-20. According to historian John Barry, “Those most vulnerable of all to influenza, those most likely of the most likely to die, were pregnant women.” He estimates that when influenza necessitated hospitalization, it was fatal for mothers and children about half the time. For those women who survived, about one in four lost the child.

The deaths of Annie and her unborn child on November 14, 1918, was a turning point for Lillian Gordy Carter. When she remembered those traumatic days decades later, she blended three events into one: celebrating Armistice Day, mourning family deaths, and applying to work as a government nurse. “My sister’s death caused me great agony,” Carter remembered, but it also infused her future with meaning. “I thought, oh, how I would like to spend my life doing something like this.”

Hundreds of families just like the Gordy family lost loved ones in southwest Georgia. The 1918-20 influenza pandemic is often called “forgotten history.” Yet Lillian Gordy Carter’s story reminds us that individuals carried strong memories of the pandemic for the rest of their lives. Other stories were passed down through generations. Sara Burkhalter, a member of the extended Hooks family, fell ill on January 12, 1919. Educated at Sweet Briar College in Virginia, Burkhalter delayed marriage and children until her thirties. She was engaged to be married in 1919 but died before her wedding day.

Private memories persisted despite a collective forgetting of the pandemic at the national level. In communities across the country, records from the influenza pandemic—like flashbulb memories of someone else’s nightmare—have resurfaced in recent decades as recent fears over HIV, SARS, and now Covid-19 necessitated a reawakening of local and national memories.

Counting the Victims

We can neither count nor put a name to all of the 1918-20 influenza victims. Historians believe the pandemic killed about 675,000 Americans and about 50,000,000 people worldwide. How many died in Americus, Sumter County, or southwest Georgia is difficult to estimate. With a single exception, every named victim in the Americus Times-Recorder was white and most represented the middling and upper-class residents. While it is an irreplaceable source, the newspaper did not preserve a comprehensive record of the city’s lived experience.

Influenza deaths were not a great equalizer. Separate and unequal segregation created a wide divide in medical care across the county. Twenty of the 24 physicians in the 1916 Americus and Sumter County directory were white. There was not a Black hospital in the county until 1923. This disparity in public health had consequences.

Death Certificates, better kept and preserved in 1919 than any earlier years, offer another partial portrait of victims. According to 45 reported influenza and pneumonia deaths in January, February, and March, the average victim age was 28, the median age was 24, and more 16-year-olds died of influenza in Sumter County than any other age. Women made up 64% of fatalities. Although the county population was split almost evenly along black-and-white racial lines, African Americans accounted for 62 percent of reported influenza deaths. The most common victims were African American females, who accounted for 44 percent of all influenza deaths recorded on death certificates. Extant death certificates from 1919 suggest a large number of missing African American victims—especially Black women and girls—in October, November, and December 1918.

Walking in cemeteries offers another view of the pandemic. For one thing, examination of cemetery and death records shows that not every death certificate has a preserved headstone; in a similar way, not every headstone from peak pandemic months has a corresponding death certificate or obituary. In the winter of 2020-21, while still learning how to navigate the Covid-19 pandemic as a new parent, my infant daughter and I drove all over Sumter County and slogged through cemeteries looking for these memorials. Sometimes I carried a list of names from death certificates or obituaries. There was Lee Patton, a Confederate veteran buried at Rehoboth Baptist Church, R. L. Bass, a 9-year-old buried at Mt. Zion Cemetery, and 26-year-old Ruth Page Pryor at the De Soto United Methodist Church cemetery. Other times, we simply looked for graves that might have some connection to pandemic. We spent hours in Oak Grove Cemetery alone.

The exercise reminded me that time has not been neutral in memorial and cemetery preservation. The vast majority of extant headstones commemorate the lives of white men, women, and children. For instance, my daughter and I had no luck climbing through the brush at New Corinth Baptist Church, where 37-year-old Jim Mitchell and 16-year-old Eula Lee Cheney are buried. Eastview Cemetery also contains many unmarked graves—some of which can be found by plotting known graves and approximating the location of the unmarked ones. We used this method to find the unmarked graves of 39-year-old Ann Dennard, 44-year-old Hattie Patterson, 2-year-old Emandra Hart, and 69-year-old Lucinda Williams. All-in-all, there were about 80 “reported” influenza deaths in Sumter County and many times that number of “likely” or “possible” pandemic victims.

Of these influenza deaths, perhaps the best-memorialized victim is Wade Barrington Lott. An alumnus of the Third District Agricultural and Mechanical College, the school that became Georgia Southwestern State University, Lott served the U.S. military as a marine and drill instructor at Parris Island, South Carolina. When he died of influenza in November 1918, the city and the school mourned his death. The city planted a tree, probably a magnolia, at the Americus and Sumter County Hospital on Dodson Street. The college named their library in his memory. The library remained as a memorial to a local soldier and influenza victim for half a century.

Pandemic Pedagogy

In the spring of 2021 and 2022, Georgia Southwestern State University students in my Study of History course used the historical pandemic to build individual and collective class projects, culminating in creating a website, Influenza in Americus (https://www.influenzainamericus.com/). The class introduced students to how historians ask questions, research, and write. We read scholarly works and connected local stories to big picture topics. We learned how to review secondary, scholarly literature as well as conduct digital primary sources research. Students discovered that studying history requires not only historical records but also active imaginations and critical thinking skills.

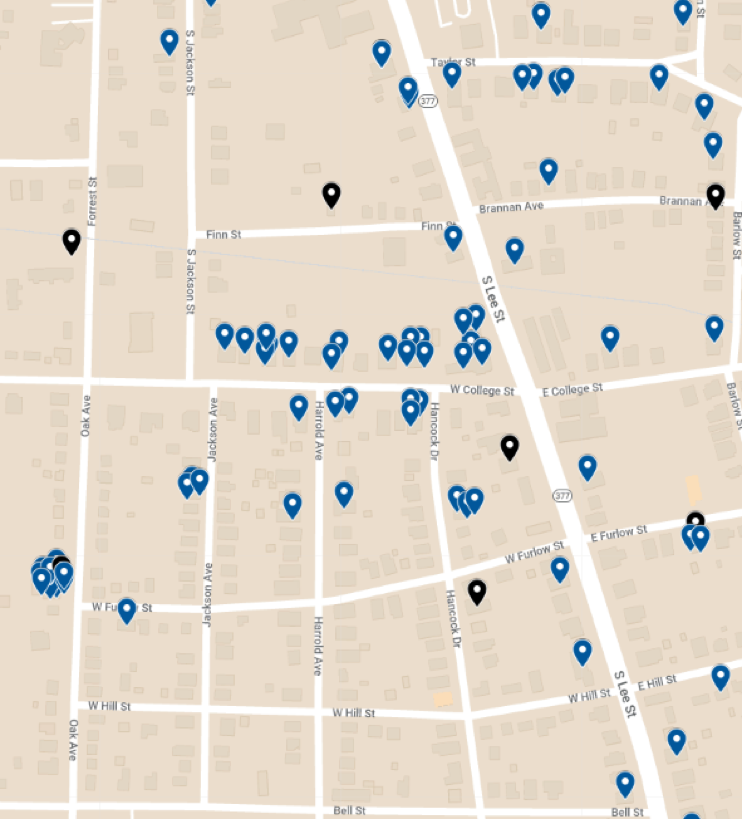

The website offers an overview of the pandemic in Americus as well as a series of in-depth looks at individual stories. Students picked people to study and wrote short essays connecting their lives and deaths to the local and global history. They began their research with an obituary or a death certificate and used census records, city directories, maps, draft registration cards, and the extant landscape to flesh out the life histories or “un-obituaries” of influenza victims and survivors. Students also visualized how the newspaper reported on illness. The “local news” and “society” pages, it turned out, mentioned many of the sick by name. While not all of these illnesses were influenza and the newspaper focused on white middle- and upper-class residents, the map begins to show the depth of the pandemic during its peak months.

The students also began taking small steps toward preserving the local experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic. The lack of first-person accounts from 1918 and 1919 led us to interview, transcribe, and preserve ten oral histories narrated by local residents who agreed to talk about their experiences through our own pandemic years. There will be gaps in the local experience of Covid-19, but—if the right steps are taken now—there will be a better archival record thanks to the work of these GSW students: Andrew Bellacomo, Brooks Bowden, Chandler Bowman, Bobby Brooks, Hayden Hatcher, Saksit Jairak, Shawn Lunde, Julia Vela, Conner Vizzini, and Evan Ward.

Life in the Past Lane

The student-produced website is one example of the opportunities for exploring the rich history of Americus, Sumter County, and southwest Georgia. This work continues. As a professor and a practicing public historian, I will strive to work with students and community members to learn more about our shared past. There may be more newspaper articles. Yet this will be the final installment of my regular, monthly submissions. Important local stories are inexhaustible; however, I want to conclude while I am still having fun. After three years, 38 articles, and 65,000 words, I am not exhausted, but it is time to apply my energy elsewhere.

Thank you, as always, for allowing me to write about these important histories when we agreed and, perhaps especially, when we disagreed.