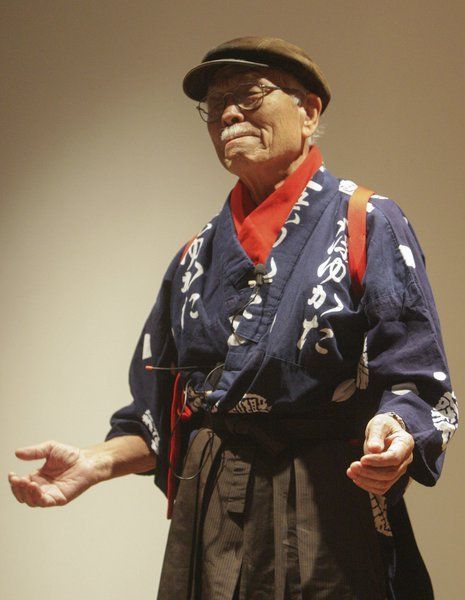

Man who lived through Hiroshima tells of emotional journey

Published 1:30 pm Wednesday, March 25, 2015

In the aftermath of the first of two atomic bombs that ended World War II, Hiroshima bombing survivor Takashi Tanemori experienced loss, shame, rage, torture and pain, but he ultimately found faith, peace and forgiveness.

He was less than a mile from the impact when the Enola Gay dropped the “Little Boy” bomb on the city. He didn’t know what had happened or why. The light was white. It was so bright and penetrating, he could see the bones in his hands.

“Yesterday we had the opportunity to go to Oklahoma City and look through the museum of the Oklahoma bombing,” he said. “The moment I step on, I see the little water, then the chairs. The first thing that returned to me is when we crossed the river behind the school (in Hiroshima).”

Speaking to an overflow crowd Tuesday at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman, Oklahoma, Tanemori recalled the events as though they were 70 hours ago, rather than 70 years. He described how a soldier found him and took him to the river where they crossed a grisly bridge to find his father.

“We crossed the river, not on the bridge, but a bridge made of all the debris of human bodies,” he said, “washed against the pilings of the bridge … The many, many people had tried before us and built up their part of the bridge. So by the time we crossed, the bridge was strong. Thousands and thousands of human bodies washed against the pilings. When I go to the Oklahoma City bombing, I see the water.”

He described in relatable terms what that day was like. He asked residents to imagine that they all went to collect dry leaves by the sack-full and truckload and brought them to Norman. They would build a wall 10 feet wide and 20 feet high around the university with the leaves and douse it with gasoline. Then, light the wall at every point around the university simultaneously. Then they would see all the students, professors and children inside, trying to escape, looking futilely for a way out.

“Don’t you see your children inside the wall, squirming, trying to escape?” Tanemori said. “But there’s no escape.

“There I was, seven-tenths of a mile from ground zero — without knowing what did happen. Try, try to escape the heat — 6,000 degrees, the heat.”

The story returned to the soldier who found the then-8-year-old Tanemori at the river where they crossed the bridge of bodies.

“I saw many people, wrench, crawl, stepping over, shoving to go to the waters of the river,” he said, crying. “They just went, like a dog lapping water, but no one ever got up. The moment they hit the water, they drank the water. That was the last moment I ever seen, I ever witnessed. People screaming, ‘The water, water, water.’ The water is a source of life, but yet, the many watching, this time it killed them.”

The boy heard his father calling for him as he watched the scene with the soldier.

“That’s my daddy,” he told his rescuer. The young man took the boy to his father.

After being reunited with what little family he had left, Tanemori saw his father thank and praise the soldier.

“You are the savior of my son. Arigato, arigato, arigato,” he heard his father say, using the Japanese word for “thank you.” He watched the young man walk back into the city to his base.

Tanemori’s father took him to live with his maternal grandmother, who lived some distance outside the city, only to be shamed publicly by his mother-in-law for not returning with her daughter. The boy’s father returned to the city many times looking for his wife and missing children, never to find them.

On his death bed, Tanemori’s father told him to live as he had, by the code of the samurai. He, at the age of 8, was expected to carry the family legacy and honor.

At the age of 18, the boy who was now a young man, came to America seeking vengeance for the death of his family, the destruction of his home and redemption for his father’s shame.

Upon arrival, Tanemori was placed in a migrant labor camp. The doctors treated him for several days before realizing he was a survivor of Hiroshima, and he was moved to a medical facility to be studied as a test subject for radiation poisoning.

Through all the torture, pain and inhumane treatment, he never forgot his father’s shame. The pain of the spinal taps twice a week was bad, but not as bad as the shame. He believed he had failed his father. The boy had not lived up to the commission he accepted from his father before he died.

After Tanemori was released, he became an anti-war activist and an anti-American favorite of protesters in San Francisco and Berkeley, California. It was on the way to a speak at an anti-nuclear rally on the 40th anniversary of the destruction of Hiroshima when Tanemori remembered his father’s words. Combined with his newly found Christian faith, he came to a realization.

“It was much later, years later, I came to know Christ as my personal savior,” he said. “Combined with my father’s teaching, my personal faith in Christ Jesus was consummated. … I want you to know, I forgive Americans. On Aug. 5, 1985, 40 years later, I was asked as guest speaker. … Everybody yell my name, ‘Yeah, Takashi, go after! Anti-American, Anti-nuke.’”

“But revenge gets revenge, anger gets anger. As my father say on his death bed, ‘Takashi, the greatest revenge on your enemy is by learning to forgive.’”

Chilton writes for The Norman (Ok.) Transcript.