The children left behind when the American soldiers departed from Vietnam

Published 10:45 am Monday, April 20, 2015

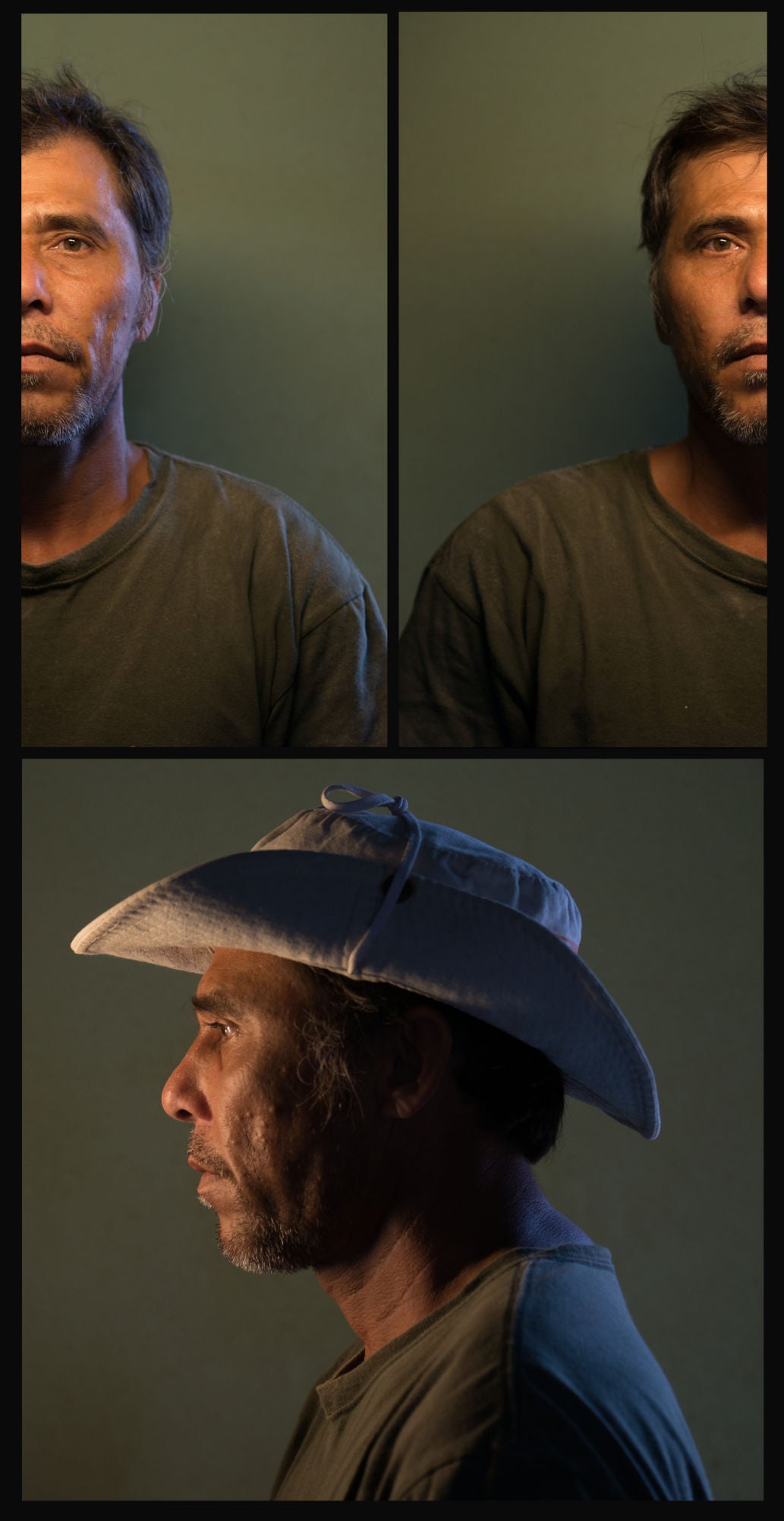

The Businessman: Dang Van Son

The bar girl fell in love, or something like it, with an American serviceman named Jackson stationed at Long Binh base near Saigon in 1967.

The two set up housekeeping in a home on a noisy street in town, and the soldier used to come by in the afternoons and take the woman, Nguyen Thi Canh, for rides in his Jeep. After a while a baby boy arrived.

It was a cozy setup, a neighbor who is still alive recalls, but it didn’t last long. Eventually Canh took the baby and a bundle of the soldier’s cash and got back together with her ex-husband, with whom she had already had seven children. The family eventually left Saigon and went back to their home town in the Mekong Delta.

The boy, Dang Van Son, grew up being abused by his stepfather and always wondering why he was treated differently from his half-siblings. One day after a particularly brutal beating, an aunt pulled him aside and told him that he was being mistreated because he was the child of an American soldier.

Remembering the moment, he still weeps more than three decades later.

“I felt sad, really sad when my aunt told me,” Son said. “I always felt I didn’t look the same.”

After his mother died of cancer in 2000, Son made his way to Saigon, now called Ho Chi Minh City, with the equivalent of $2 in his pocket, working low-paying jobs and saving enough to open a shop manufacturing tailor’s chalk.

As the owner of a thriving business, Son is a rare success story in Vietnam’s mixed-race community. Others were bullied, left school early and now live on the margins, scraping by with menial jobs.

Son lives with his wife, son and daughter in small quarters above the shop. He is certain that life will be easier for his children, because attitudes toward Amerasians have shifted as Vietnam and its society have developed and globalized. His daughter, Dang Thi Kim Ngan, was teased in school for her curly hair, “but nobody said anything racial,” she said.

Ngan, 19, is now a college student studying for an associate’s degree in tourism.

“It’s a lot easier now,” she said. “People don’t care where you’re from as long as you can work and be successful.”

— — —

The Couple: Nguyen Thanh An and Le Thi My Thuy

When Nguyen Thanh An first saw his future wife, Thuy, selling soft drinks at the beach 15 years ago, he knew instantly she was “mixed” — just like him.

The two bonded quickly over their difficult childhoods, when they were ostracized because of their racial heritage. The couple began dating, had a son and married in 2007.

“There’s a lot to talk about. We share the same past, the same feelings,” said An, 45, who works as a mechanic in Binh Duong province.

After the fall of Saigon in April 1975, An was given up for adoption because his family feared they were being watched by the Communist Party and were in danger. His mother later committed suicide, and the remaining family members fled Vietnam by boat, like thousands of others.

An says his adopted parents were cruel and ultimately tried to sell him to another family who hoped to use his American heritage as a ticket to immigrate to the United States. He ran away and spent most of his early life in and out of orphanages and on the streets.

After the Communist takeover, his wife, Le Thi My Thuy, like many Amerasians, was sent with her mother to a rural work camp as part of the country’s collectivization movement. She and her mother left the camp and eventually found work transporting baskets of fish.

An and Thuy know next to nothing about their fathers — although they both firmly believe they are children of U.S. soldiers stationed in Vietnam during the war. But having little proof has made immigration next to impossible.

Thuy, 42, shows off her yellowing U.S. visa paperwork denied in 1996 with the scrawl: “does not appear Am/no proof American father.”

The couple live with their son in a dormlike apartment building in an industrial park about two hours from Ho Chi Minh City. Thuy runs a small store out of the front of the apartment. Together they earn about $140 a month.

“It’s still very hard, but not as hard as before, ” Thuy said. “We struggle financially, and we don’t have any other family, but we share that hardship together.”

— — —

Sandy: Tran Thi Huong

Her name is Tran Thi Huong. But she calls herself Sandy.

That’s the name her American father gave her before the Army sergeant shipped out of Cam Ranh Air Base in 1969 and left his girlfriend and their infant daughter behind. He had been excited about Sandy’s birth, even having a special picture taken with her. But he left without saying goodbye.

That photo, all that remains of her parents’ love affair, was carried like a kind of holy relic to the United States by relatives, where it finally ended up last year in the hands of Sandy’s energetic American cousin, Anh Tran, an event planner in Philadelphia. Tran last year set out to try to find Sandy’s father.

She knew the soldier’s name but little else about him. With the help of a volunteer group that links veterans and their children, Fatherfounded.org, she located him after about three months. He was living in Cleveland.

Although the former soldier’s American daughters eventually confirmed that the man in the photo was their dad and have welcomed the idea of a half-sister in Vietnam, the gruff, aging veteran has had little to say about it and has not contacted his child.

Such outcomes have been common for Amerasians; only about 3 percent of those who have immigrated to the United States have reunited with their fathers, according to one government estimate. Many fathers don’t want to be found or just want to forget about their traumatic time in the war zone.

Sandy, 45, typically rises early in the morning to harvest snails from the ocean bottom at low tide. She cooks them in a small restaurant in front of her home in Cam Ranh that has become a neighborhood gathering spot. Friends come by to sit in the open air, gossip, pick the meat out of the tiny bluish shells or sample one of her other specialties, sticky rice and pork fat wrapped in banana leaf.

Her mother, with whom she remains close, lives nearby.

Sandy is aware that her cousin has found her father, but little has changed in her life since the discovery.

“I really want to see my father again,” she says quietly. “Maybe they can come to meet me?”

— — —

The Tailor: Nguyen Thi Thuy

When Nguyen Thi Thuy was a child, she tended a herd of water buffalo on her adopted family’s farm. The animals were her only friends, she says.

Half-black, half-Vietnamese in the city of Cu Chi, Thuy says she was constantly teased and bullied by her classmates and neighbors. One terrifying day a mob followed her, calling her “black American,” throwing stones and poking her with sticks.

Thuy was put up for adoption by her mother after the war because, the mother says, she was afraid of what the North Vietnamese would do to her if they found out she had a mixed-race child.

The stepfamily made Thuy work long hours in the fields, Thuy said. She loved school and managed to stay on until 12th grade but had to drop out because she didn’t have the funds for the required school uniform.

She went on to apprentice as a tailor and then to open her own shop in a small kiosk. She married a laborer who loved her and said he did not care she was Amerasian. They had two girls, now 12 and 14.

Thuy, now 42, had gone looking for her birth mother when she was about 18 and found her in a town about an hour away. She was not pleased to see Thuy. “How did you find your way here?” she demanded.

Her mother had started life over again with a Vietnamese man and had five more kids. She was cool to Thuy, afraid her presence would jeopardize her family situation.

The two have a maintained a distant and complicated relationship ever since. The mother has given her different versions of the name of the soldier who was Thuy’s birth father, which has complicated her search. Thuy is hoping the DNA database testing will help.

The thought of one day finding her father is the only motivation that has kept her going through the years, she says.

“When I was tending buffalo alone in an empty field, I used to look up into the sky and think, ‘He must be in a faraway place,’ ” Thuy said. ” ‘I don’t know if he’ll ever be able to find me and take me away from this life.’ ”

— — —

The Worker: Nguyen Thanh Trung

She was a kindergarten teacher. He was the maintenance man at her school.

When Nguyen Thi Ngoc Phuong first met her mixed-race boyfriend, she says she was ambivalent because he was uneducated and his unusual looks — half white, half Vietnamese — unnerved her. But her family pressured her to commit to the relationship.

“My mother said, ‘If you want to go to America, you should marry him,’ ” Phuong, 47, recalled recently.

It was the 1990s, when many Amerasians were applying for the new American resettlement program for the children of U.S. servicemen born in Vietnam. The problem was that Nguyen Thanh Trung knew little about the man he thought was his father, except that his name was “Sandy” and he cleared mines as a soldier in the Army’s 25th Infantry Division, stationed at Cu Chi Air Base. Trung’s mother did his laundry.

Like many mothers of Amerasian children, Trung’s had burned all the soldier’s letters and photos after the Communist takeover, fearful of being accused of consorting with the enemy. She gave Trung to his godfather to raise. Trung grew up being taunted by his classmates as an “American imperialist” and dropped out of school after just a few years.

When he finally asked his mother about his heritage, she said the soldier knew she was pregnant when he shipped out and said he would come for her one day.

She waited 20 years.

Without the proper documents, Trung, 46, failed to get his immigration visa. By that time, his wife-to-be said she had figured out what a “good, decent” guy he was, so she married him.

Trung and Phuong live with their extended family in Cu Chi, near Ho Chi Minh City. Phuong is still a kindergarten teacher, and Trung does tile work for a construction company that builds homes. Their biggest worry these days is how they will afford to send their daughter, who is in her last year of high school, to college.

“I still want to immigrate, but I have no documents,” Trung said. A positive DNA test, he said, “is my only chance of getting out of this country and away from this hard life.”

If he ever finds his father, he says, he has just one question for him: “Why did you leave me here?”