End of innocence: The unsolved murder of Leigh Bell, 40 years later

Published 1:42 pm Wednesday, June 5, 2019

Part 1: The Disappearance

By Beth Alston

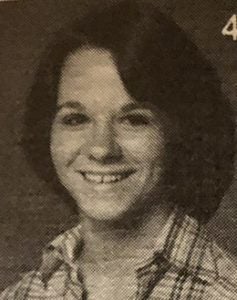

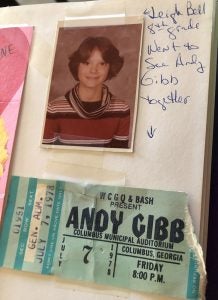

NOTE: The information contained in this five-part series is taken from the murder case file and interviews with key individuals, and media reports. Those interviewed include law enforcement, a local journalist, and friends and family of Leigh Bell. The case was officially closed on Feb. 15, 2019, by Lewis Lamb, Southwestern Judicial Circuit District Attorney, following the death of the last suspect. Leigh Bell, a 15-year-old cheerleader, and daughter of the Americus city manager Leland Bell, disappeared on the evening of June 6, 1979.

AMERICUS — If was 1979, the first full week of summer vacation as school had just let out the previous week. The softball leagues — both city and church — were playing at the complex behind Americus High School, on field between Harrold and Oak avenues. Lots of folks were out — to play or as spectators. They were teens, college students, and families out on a fine summer evening to enjoy America’s favorite sport in a heretofore innocent, small, southwest Georgia town of Americus. The long days of summer were in full swing so it would be 9 p.m. before dark-thirty arrived. A brief rain shower drove some people out of the park and to their homes, while others waited it out until the games resumed. Some made it home dry. Some arrived at their doors slightly damp. One never came home.

June 6 marks the 40th anniversary of the murder of Margaret Leigh Bell, a petite, 15-year-old cheerleader at Americus High School, who was a rising sophomore. While the man who was ultimately arrested and charged in her rape and murder, George Gignilliat, was acquitted by a Macon County jury, there has been no closure and no sense of justice in the case in the ensuing four decades. The crime struck terror in the hearts of the community, robbing the town of its innocence.

Members of the Bell family, friends of Leigh Bell, as well as other members of the community remain bitter about the unsolved crime, a crime so horrendous that it literally broke the trust of many residents. Parents no longer allowed their children to play outside without supervision. Teen-aged girls were no longer free to go out riding around with friends. People who had never given safety a second thought began locking their doors and peeping furtively through their blinds at the slightest noise.

Best friends forever

On the night of June 6, Leigh Bell was at the ballfields with her best friends, Patti Horton (Griffith) and Syndey Connelly, stepdaughter of then-Macon County Sheriff Charles Cannon. They hung out and talked, as teen girls do. They ran into various other friends they knew. Everyone knew everyone and, after all, it was the first week of summer vacation. The three girls were always at one of their homes or the other, according to Griffith, who was recently interviewed by the Times-Recorder. Griffith and Bell were best friends, since fourth grade, she said. Griffith lived across town on Armory Drive while Bell lived on Glenwood Road, just a few blocks from the ballfields. Griffith said it was common for her to ride her bicycle across town to visit her best friend and they were free to ride around “all over.” She said that back then, “it was a completely different way of life.”

“From sixth grade on,” Griffith said, “we were together every weekend at her house because it was in town. We would walk all around … the neighhorhood.” She recalled that while in junior high school, she and Bell, along with many others would swim in the pool at Country Club Apartments on South Lee Street.

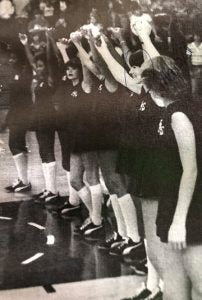

Americus High School cheerleader Leigh Bell is shown third from left. She and her best friend Patti Horton (Griffith) were both members of the squad.

Although tearful at times during the interview, Griffith seemed to enjoy remembering her best friend and their young days together. She smiled wistfully recalling that she and Bell played “Starsky and Hutch,” the then-popular TV show about a duo of young detectives, and later, with Connelly, they played “Charlie’s Angels,” another popular TV show about a crime-solving trio, and later a movie. Kids in small towns often had to use their own imaginations being that there were not many places for younger kids to gather.

Griffith said she and Bell were so close, that, while attending Staley Middle School, they would go into the girls’ restroom stalls in the mornings and swap outfits, both being the same, petite size. Although Griffith has two sisters, both older, and Bell had two sisters, one older and one younger, the two girls, Griffith and Bell, were “even closer than sisters,” according to Griffith, who said they did everything together. “Then you get to high school, and you get boyfriends, and you don’t do as much together.” She said she and Bell had classes together their freshman year and Bell was “super smart.” They were also both on the Americus High School cheerleading squad.

Griffith said that Connelly, who lived in Macon County at the time, had come to Americus the first week of summer vacation and the three girls stayed at Griffith’s house Monday night and at the Bell home Tuesday night. On Wednesday night, the three met at the ballfields. Griffith recalled seeing George Gignilliat, an older guy at age 27, at the ballfields either Monday or Tuesday night prior to Bell’s disappearance. “He was trying to get her (Bell’s) attention and trying to pull her into conversation,” she told the Times-Recorder, as she, Bell, Connelly and Bruce Bivins were sitting together on the bleachers. “She [Bell] told us, ‘that’s him; that’s the guy,’” Griffith said, explaining that the prior Friday night, Bell had gone to the graduation ceremony, and afterward a party at Lee Smith’s house and another at a fraternity house on Taylor Street. “That’s really where it started,” she said, referring to what she called Gignilliat’s fascination with Bell.

It was around midnight that Wednesday night that the phone rang at the Horton home (Griffith’s childhood home). It was Leland Bell, Leigh Bell’s father, asking if Leigh was with Patti. She was not. Griffith recalls that she and her parents got into the car and drove around, not really knowing where to go, “just looking for her [Bell].”

Griffith was interviewed around 7:50 a.m. the following morning, June 7, by then-Sumter County Sheriff Randy Howard and Deputy John Durden. She told them that around 9 p.m. that Wednesday night, Bell told the others that she was tired and thought the church league game was boring and she was walking over to the city league field, and if nothing was going on there she would leave and go home. “She [Bell] then got up left and walked across the highway back toward the gate, which is located on the northwest side, which goes to the city league. This was the last time that Patty [sic] saw her [Bell],” the statement read.

The car that Bell was driving home from the ballfield that night was located late that night by her father, blocking the driveway at 1123 Harrold Ave. Leland Bell couldn’t crank the car, which belonged to his wife, so he let it roll backward until it cleared the driveway.

Griffith said she stayed at the Bell home during the time between Leigh Bell’s disappearance and when her body was recovered. She said she couldn’t remember a lot of it, and “it was a blur.” She said she could not recall attending her best friend’s funeral, but of course she had. She said Bell’s cousin told her recently that Griffith had to be carried in to the funeral service, none of which she remembers. She said her mother and one of her sisters told her that she had just not wanted to talk about it that summer, and she spent a good bit of time with another of her sisters at her home in Bainbridge that summer. She said she was not allowed to go anywhere without her parents or Brian Bodine, the young man she was dating at that time. She said she found out later that someone had called and said that she would be next. Nothing can be found to verify this, and she said she had been told this. “It was just crazy the stuff that was going on,” she said.

Griffith said she didn’t know “those people,” such as Greg Farr and George Gignilliat. “I wasn’t allowed to go as much Leigh did. She had a lot more freedom than I did.”

Griffith said she thinks of Leigh Bell a lot. She gave her eldest daughter Leigh as her middle name and her daughter named her own daughter Leigh as a middle name as well. What Griffith struggles with today, she said, is not even letting her mind go there, “because if you go there, if you really start thinking about the evil … ” She said she lost a neighbor in sixth grade in a car wreck. “That’s a loss, but I’m not going to go into a deep, dark place of torment … ”

Today, Griffith said she tells her children that she has to always know where they are so she can reach them. “I freak out if I can’t get them,” she said.

When the new school year began in the fall of 1979, it began without Griffith’s best friend, but she said other girls made a point of inviting her to do things, “but it was strange,” she said, noting the absence of Leigh Bell. Even today, Griffith tearfully remember her best friend Leigh Bell. “I love her and I miss her,” Griffith told the Times-Recorder.

Search begins

Randy Howard, who was then Sumter County Sheriff, was also interviewed recently for this series. He said Leland Bell, who was Americus city manager and whom he was personally acquainted, called him late the night of June 6 to report his daughter missing. Howard said he immediately went to the Bell home on Glenwood Road. The following morning, early, the sheriff visited the apartment of Debra Slaughter, Gignilliat’ girlfriend, at Kingstowne Apartments. Gignilliat said he had been there all night since around 11 p.m.

According to documents, at 9:05 a.m. June 7, Georgia Bureau of Investigation Special Agent Scott Roberts spoke with Randy Howard who said Leland Bell had reported his daughter Leigh Bell missing after attending a softball game the night before. She left her residence between 7:30 and 8 p.m., driving her mother’s car. She was supposed to return home by 10 or 10:30 p.m. and did not. Howard said Leland Bell had gone out looking for his daughter around 1:30 a.m. June 7 and found his wife’s car blocking the driveway of 1123 Harrold Ave. He attempted to crank the car but it was low on gas when she left to go to the softball game. Bell let the car rollback approximately 1o to 15 ft. to unblock the driveway.

Howard described Leigh Bell as a “quiet female,” 5’2” tall, weighing 100 pounds, black hair and brown eyes. She was last seen wearing a maroon blouse and blue jeans.

Cathy Bell, Leigh Bell’s older sister, told authorities that she at the city league ball field on the night of June 6, and she saw Gignilliat, Derek Henderson, and Randy Bishop at the ballfield at approximately 10 p.m. in a green Camaro. Gignilliat was driving.

By the next morning, everyone had heard that Leigh Bell was missing. Her friends were shocked and some even took their dogs out looking for her.

The place where the car Leigh Bell was driving home June 6 ran out of gas, right in front of 1123 Harrold Ave., near the intersection with Glessner Street.

It would be later revealed in an interview with Meredith Reese (now Wilson) that she saw Bell the night she disappeared. Wilson could not be reached for this series. However, the transcript from her interview, under hypnosis with a psychologist brought in from Augusta by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, was available in the case file. Wilson recalled riding her bicycle in the area of the high school the night of June 6 when she saw Bell outside a car on Harrold Avenue near the intersection with Glessner Street. She stopped and asked Bell is she needed help and Bell explained that the car was out of gas. The two girls got the car out of the street, and left it in front of 1123 Harrold Ave., where Bell’s father would later find it. Wilson asked Bell if she wanted her to go home with her or back to the ballfield with her but Bell said she was going to walk to the ballfield and get her sister Cathy.

Glessner Street, facing toward Oak Avenue, where witnesses would see Leigh Bell walking the night of her disappearance.

At least two people told authorities that they had seen Bell riding in two different cars with two different drivers, one near the ballfields and the other at McDonald’s. Both men said they waved at the girl they thought was Leigh Bell and she didn’t wave back.

Body discovered

Greg Barfield, who knew Bell, told authorities when interviewed that he was not at the ballfields on Wednesday night but that around noon the following day when his mother told him that Bell was missing, he, Brian Mathis and Tommy Holloman began searching for her. Documents in the case file state that the young men searched by the natural gas plant on South Lee Street. Barfield said the next day, Friday, June 8, between 9 and 9:30 a.m., he and several friends searched both sides of the road on Ga. Highway 377 (South Lee Street Road), and “walked the tracks around the sewage disposal plant at the end of Valley Drive … After lunch they began searching the area at the intersection of Lee Street Road and Twin Bridges [now McLittle Bridge Road.] They turned off the dirt road at the bridge and went back under the bridge and found a pair of panties. They walked around and did not go under the bridge. They saw some marks under the bridge and became certain they had found the site. They left five persons at the scene at the bridge and went back and informed the authorities.”

A tracker from Dooly County was notified and he came to Sumter County with his dog. At the Muckalee Creek bridge on Twin Bridges Road (now McLittle Bridge Road), south of Americus, the dog was used by its handler, Van Peavy, to track the scent of Bell by clothing from the girl’s parents. Three times, the dog went straight to the creek bank. Peavy, upon entering the creek, felt something against his leg. It was the body of the missing girl.

At approximately 3:35 p.m. June 8, Bell’s body was removed from Muckalee Creek, near the bridge “lodged in some branches and a log that were submerged in the creek.” The body was examined on scene by then-Sumter County Coroner Larry Hancock and then taken in an ambulance to Americus-Sumter County Hospital.

Read Part 2: Discovery and investigation in June 12 edition of the Americus Times-Recorder.