“Very Relieved that the Primaries are Over”, Pres. Carter Earns 1980 Delegate Majority

Published 12:11 pm Wednesday, June 24, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: D. Jason Berggren

Note: D. Jason Berggren is an associate professor of political science at Georgia Southwestern State University. This is the seventh article in the Carter 1980 look-back series.

June 3 marked the end of the 1980 presidential primaries, and, with a clear majority of convention delegates expected to go his way, Jimmy Carter became the presumptive nominee of the Democratic Party.

Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy, who had his best election day of the 1980 season with wins in five states, declined to offer an endorsement and was determined to press forward.

Eight states in all held votes that day. From east to west, the states were Rhode Island, New Jersey, West Virginia, Ohio, South Dakota, Montana, New Mexico, and, the biggest delegate prize of all, California. Some called it “Super Bowl” Tuesday.

To win the 1980 Democratic nomination, a candidate needed to reach the 1,666 delegates mark. According to the Associated Press, as of June 2, Carter led the delegate count 1,584 to 845. He was 95 percent of the way there.

With the party’s proportional allocation rules, the President was bound to receive a significant share of the nearly 700 delegates up for grabs. Ohio alone could put Carter over the top. It had 161 delegates. If a clear majority went to Carter, the nomination would be his on the first ballot.

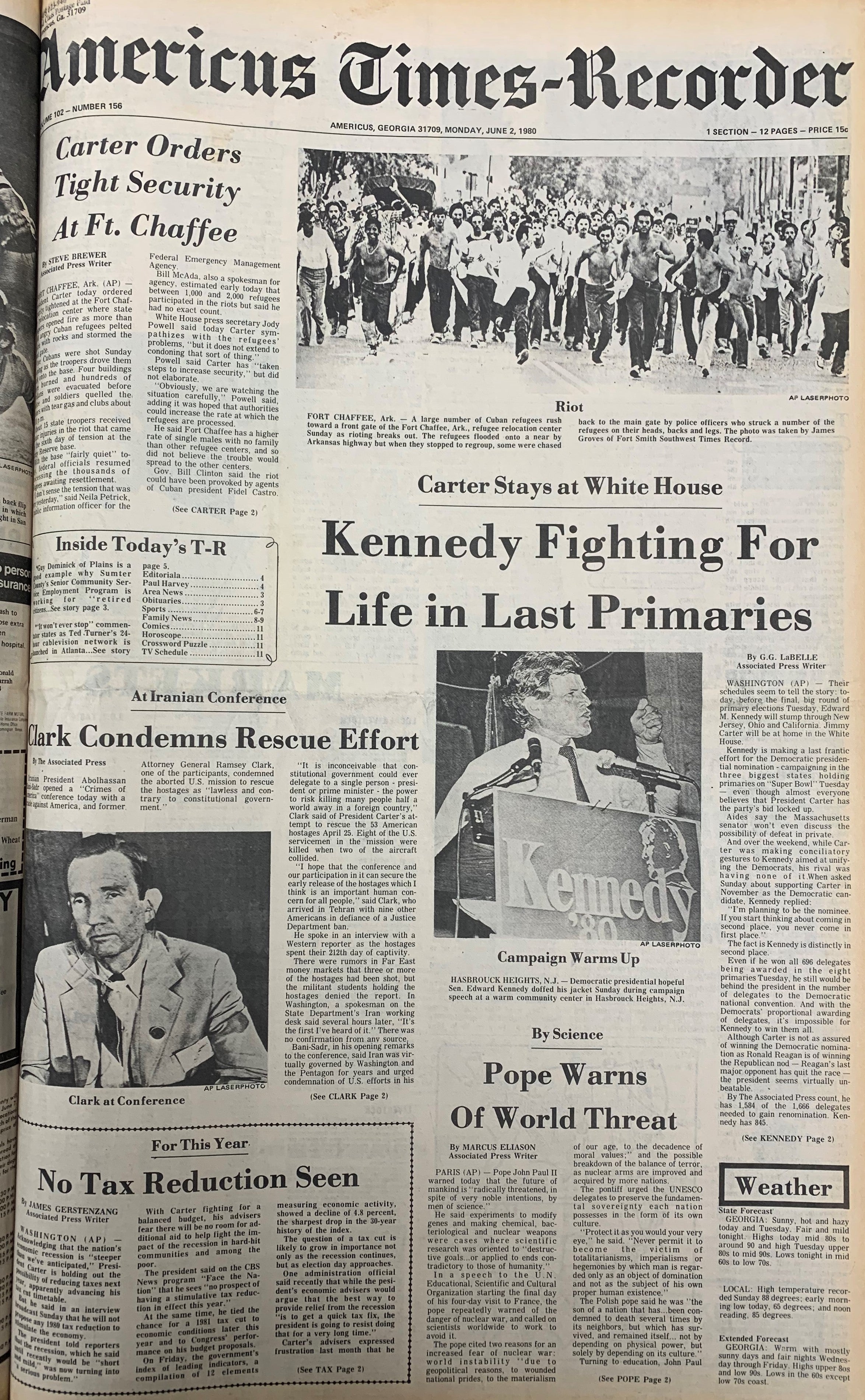

Ignoring the math, Kennedy still maintained that he would somehow become the nominee. For June 2, the frontpage headline for the Americus Times-Recorder was “Kennedy Fighting for Life in Last Primaries”

The Republican contest was effectively over with former California governor Ronald Reagan the last candidate standing. With decisive wins, the June 3 primaries officially put him over the delegate threshold he needed to win the Republican Party’s nomination at its national convention in July.

President Carter welcomed the June 3 returns. He won three of the eight states. The primary season was finally over, and he would be the party’s nominee a second time. He soundly beat Senator Kennedy and that was extremely satisfying.

Of the eight June 3 primaries, winning Ohio was particularly critical for the Carter campaign. Traditionally, it is a midwestern bellwether state that votes with the presidential winner. In the twentieth century, it only missed twice, when it went with Thomas Dewey in 1944 and Richard Nixon in 1960. Carter aimed to prove on the last primary day he could win in those areas that mattered most in November.

He did. The President won Ohio, 51 to 44 percent. He was especially strong in the central and southern parts of the Buckeye State. He prevailed in Franklin (Columbus), Hamilton (Cincinnati), and Montgomery (Dayton) counties. It was projected that Carter earned 84 delegates. That alone gave him enough to cross the delegate threshold.

Elsewhere, Carter won the primaries in West Virginia (62 – 38 percent) and Montana (51 – 37 percent).

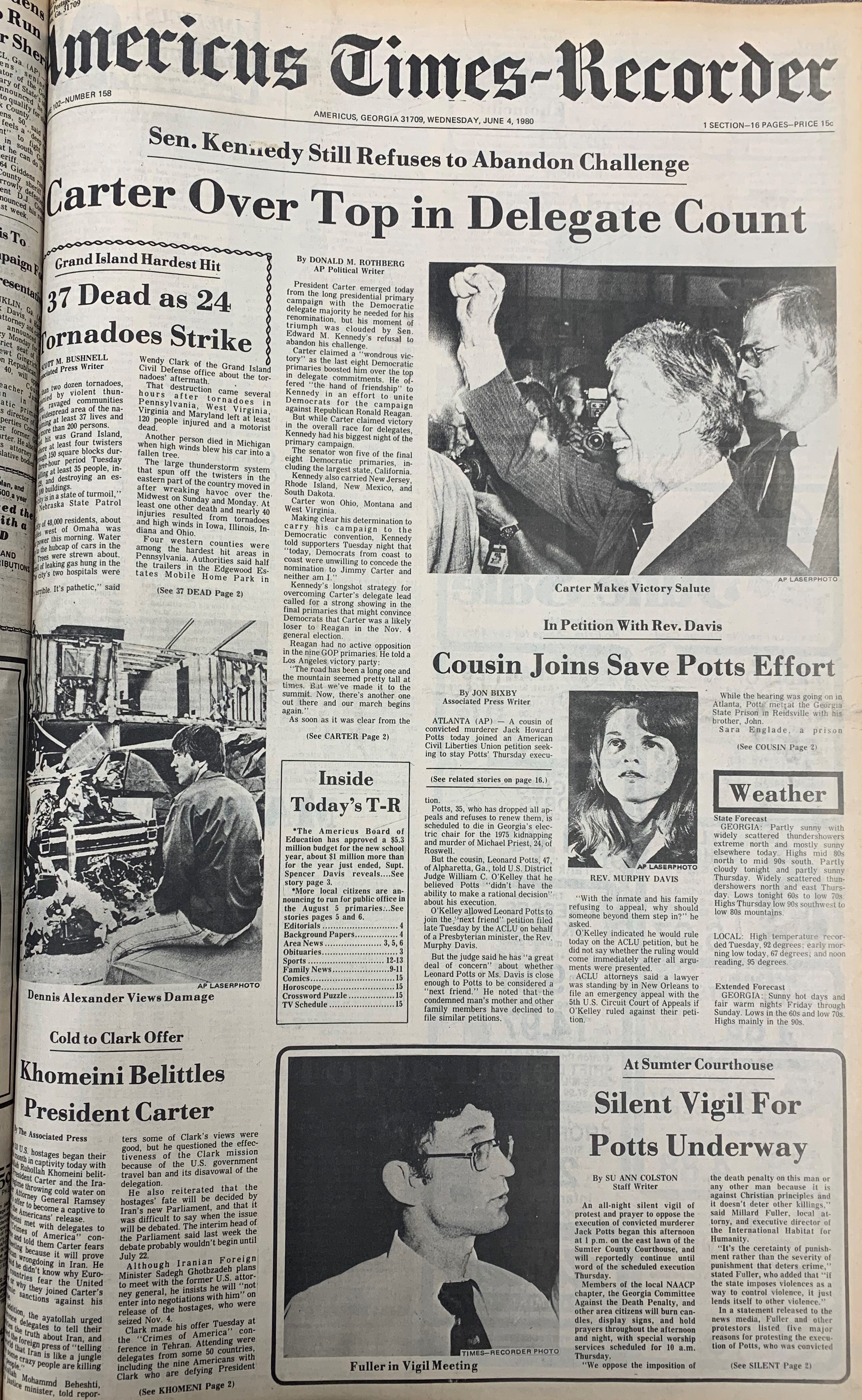

The June 4 headline for the Americus Times-Recorder was “Carter Over Top in Delegate Count”. He was sure to be the party’s nominee for 1980. For its count that day, the Associated Press put Carter at 1,921 delegates and Kennedy at 1,210.

Kennedy was thrilled with his performance. He hauled in the most delegates in the June 3 primaries. With primary victories in Rhode Island (68 – 26 percent), New Jersey (56 – 38 percent), South Dakota (49 – 45 percent), New Mexico (46 – 42 percent), and California (45 – 38 percent), the Massachusetts Senator felt somewhat vindicated. He defiantly exclaimed, “Today, Democrats from coast to coast were unwilling to concede the nomination to Jimmy Carter and neither am I.”

Primary night in Washington, the President thanked First Lady Rosalynn Carter, Vice President Walter Mondale, and other campaign workers for all their hard work in reversing “what eight months ago was a prediction of absolute defeat into a wonderous victory.”

He wrote the following in his diary. “In the last eight states, we picked up enough delegates to get a seven-hundred-delegate margin over Kennedy – a tremendous achievement, compared with what we expected seven or eight months ago.”

Carter noted that Kennedy, the one-time frontrunner, failed “so miserably”. Adding, “We wound up winning more than two-thirds of the states and a clear majority of all the votes, compared to about 37 percent for Kennedy. It’s been a long, tough, tedious, divisive primary season.”

Carter finished the primary season with 51 percent of the aggregated popular vote, and California Governor Jerry Brown, who ended his candidacy in early April, had 3 percent.

He told reporters on June 4 that he was “very relieved that the primaries are over”, “it’s a great relief”. Beginning with New Hampshire in February, he won more than twenty primaries.

Two days before the vote, Carter made history as the first president of the cable television era. On Sunday, June 1, the Cable News Network (CNN), founded by Ted Turner in Atlanta, made its debut.

During its first hour, CNN provided live coverage of the President from Fort Wayne, Indiana. He was there to visit Vernon Jordan, a prominent civil rights leader and executive director of the Urban League, at the hospital. Jordan, also an Atlanta native, had been shot on May 29 and was in recovery.

Carter spoke to the press for about ten minutes and took their questions. Thereafter, he returned to Washington. He flew aboard Air Force One JetStar for this brief trip.

As part of its inaugural coverage, CNN provided reporting on the last day of the 1980 primaries. With eight states voting, the new network dubbed it “Super Tuesday”

Also, for its first broadcast, CNN aired a taped interview with Carter. The interview was recorded the day before at the White House and then aired it in its entirety at 9 p.m. that evening. The President was interviewed by George Watson and Daniel Schorr.

One of the questions asked was about the presidential debates. He was asked why he would not debate if John Anderson, the Illinois Congressman who left the Republican race in April to run as an independent candidate, was invited to participate.

Sitting at his desk in the Oval Office, Carter explained that he was not inclined to debate two Republicans and “they’re both Republicans”. In addition, he was concerned that Anderson would take more votes away from him in November than from Reagan. “It will come at my expense more and will help Reagan.”

Carter also did an interview that weekend with CBS Face The Nation. Notwithstanding the ongoing “crisis” in Iran, it was further proof that he assuming a more active and visible role in his re-election bid.

While the nomination was to be his, it was not all roses for the President. There were new issues that added to the impression that things were spinning further out of control. One urgent issue involved Cuba.

Known as the Mariel boatlift, tens of thousands of Cuban refugees fled to the United States, beginning in April, to escape the repressive regime of Fidel Castro, who announced that any Cuban who wanted to leave the country and had a means to leave could do so

It was an overwhelming flow of people. In all, from April to October 1980, approximately 125,000 arrived. Departing from the port of Mariel, a city located to the west of Havana, most “Marielitos” came in overloaded, cramped boats to south Florida.

The large influx created a political headache for President Carter. Camps were established to house them. Reports emerged that Castro had emptied the jails and mental institutions and sent them to the United States. Much of these reports contained communist propaganda to embarrass the United States and to discredit those who wanted to leave Cuba.

Carter described the exodus as a “very challenging problem” for his administration. He vowed that the United States would not become Cuba’s “dumping ground”.

The Americus Times-Recorder ran several frontpage stories about this dramatic event. These included: “Cubans Arriving By Boat Loads” (Apr. 24), “High Seas Slow Down Ragtag Freedom Fleet” (Apr. 26), “Cuba Boatlift Continues Job” (Apr. 28), “3,000 Vessels in ‘Freedom Flotilla’” (May 2), and “4,000 Refugees Arriving Daily” (May 7).

To manage the situation, refugees were distributed throughout the country. One location was Fort Chaffee in Arkansas. Frustrated with the extended detention, hundreds protested their condition on Sunday, June 1. These protests turned to riots. Carter promised tighter security. It was another visual that the country appeared ungovernable and the presidency imperiled.

For June 2, an image of the riot appeared on the frontpage of the Americus Times-Recorder. The situation was controlled with “tear gas and clubs” applied to “heads, backs, and legs”. It was a grim look of the state of the union on the day before the final presidential primaries.

Another significant event that happened in May involved race and law enforcement. In Florida, protests and riots broke out in Miami after an all-white male jury acquitted four white police officers in the beating death of a man named Arthur McDuffie. The victim, a thirty-three years-old African American, died on December 21, 1979 from injuries received from the police days earlier.

Florida Governor Bob Graham sent in the National Guard to restore order. Prominent national civil rights leaders, including Carter’s former U.N. ambassador Andrew Young, pleaded for calm.

As part of its coverage, the Americus Times-Recorder printed these frontpage headlines: “Violence Recedes After Riots; Miami Torn by Deadly Combat” (May 19), “Violence Subsides in Miami” (May 20), “Grand Jury Begins Probe; Everything Calm in Miami” (May 21), and “Guardsmen Leave With Miami Quiet” (May 23).

On June 1, Carter said, like the shooting of Vernon Jordan, “The riots in Miami … are certainly a reminder that we need to redouble our efforts to alleviate the problems of people of all races, in all locations in our country, who are suffering from economic deprivation or some kind of social or legal justice deprivation.”

Carter was criticized for not traveling to Miami immediately after the disturbances settled. He did not arrive in Miami until June 9. Air Force One landed in the late afternoon at Miami International Airport. That day, the Americus Times-Recorder ran the story, “Cubans, Blacks to Confront Carter”.

At a meeting in Liberty City, a mostly African American section of Miami, Carter told community leaders in his opening remarks, “We all must share the responsibility for the guaranteeing of equal justice and equal opportunity, of the repair of the damage, of the treatment of people in a fair manner.”

He stressed, however, “Violence creates hatred which hurts us, and destruction of property and business places doesn’t create jobs; it destroys jobs.” Moreover, he said, “The community must realize that violence and dissension and destruction hurts most those who are least able to afford it.”

The President was in Miami for only four hours and was not exactly well-received.

On June 10, the Americus Times-Recorder published a photograph of protesters gathered alongside Carter’s presidential limousine in Miami. Some threw rocks and bottles. One bottle struck the vehicle. The photo caption was “President Visits Riot Area”. The accompanying frontpage article was entitled, “Rocks Tossed at Motorcade”. The Associated Press reporter described the boos, insults, and bombardment as “one of the most violent encounters in Carter’s presidency.”

Events such as these most likely had an impact on Carter’s public standing. According to the Gallup survey for May 30 – June 2, his job approval declined five points, from 43 percent in early May to 38 percent. Job approval numbers from fellow Democrats dropped four points to 51 percent.

The next Gallup survey for June 13 – 16 marked the end of the public rally that started in November 1979 in reaction to the storming of the U.S. embassy and the ensuing hostage crisis in Iran. In the November 2 – 5 survey, President Carter had a 32 percent job approval. In mid-June 1980, he was back down to that figure.

Carter finished the month of June at 31 percent overall and with 42 percent among Democrats (June 27 – 30).

From a rally high job approval of 43 percent among Republicans in early February, Carter was down to 22 percent in early June. In the June 13 – 16 Gallup survey, he fell further to 15 percent.

The bright side for Carter was that Gallup also showed him in a general election dead heat with Reagan. As reported in the June 18 edition of the Americus Times Recorder, the former California governor held a mere one-point 36 – 35 percent lead. Anderson trailed in third with 23 percent.

The June 3 primaries wrapped up the popular vote portion of the 1980 nomination contest. In terms of delegates, Carter was pushed over the top. He would formally become the Democratic Party’s nominee for president at the August convention in New York City.

The next task was to unify a divided party. However, as Carter wrote years later, that proved to be “an impossible task”. The Massachusetts Senator was not ready to join forces. He contended, “The people have decided that this campaign must go on.”

With the primary votes counted and the delegate math not in his favor, Kennedy refused to endorse the President and continued to make demands. He still wanted a one-on-one debate and he demanded a more liberal party platform, with stronger language on abortion rights, opposition to nuclear power, a plank for universal healthcare, and a call for an end to the grain embargo on the Soviet Union.

According to the White House daily diary, the two privately met for fifty minutes at the White House on June 5. Afterwards, Carter spoke with the press and said the meeting was “a very friendly one”. He congratulated the Senator for running “a very forceful campaign”. He was certain that he would be nominated, but he acknowledged that Kennedy was “not convinced of that fact yet.”

There was one possibility where Kennedy could take the nomination away from Carter. For this to happen, convention delegates would need to adopt a rule to free delegates from their candidate pledges. This effectively would nullify the votes of millions of Democratic primary voters and allow delegates to vote their personal preference. In such a scenario, Kennedy could win.

It was unlikely, though, that enough delegates would defect from Carter and back such a rule change. A survey of convention delegates conducted by the Associated Press found that Carter was retaining his support. In its June 30 edition, the Americus Times-Recorder printed the article, “Kennedy Failing to Gain Votes”.

Nonetheless, the Kennedy campaign pursued this option and lobbied delegates to support such a rule at the convention. Politically, it was to be a long, tough summer for President Carter.

Spending a week in Europe, June 19 – 26, for the Group of Seven (G7) Summit in Italy, a visit with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican, and stops in Yugoslavia, Spain, and Portugal, may have provided Carter some respite before the July and August party conventions. Even so, upon returning to the United States, he said “coming back home” was the best part.