Black History Month: A worthy celebration

Published 12:51 pm Friday, February 26, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

According to History.Com*, The story of Black History Month begins in 1915, 50 years after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States.

Carter G. Woodson, a Harvard trained historian and Jesse E. Moorland, a prominent minister, founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH), an organization dedicated to researching and promoting achievements by Black Americans and other peoples of African descent. Known today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), the group sponsored a national Negro History week in 1926, choosing the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The event inspired schools and communities nationwide to organize local celebrations, establish history clubs and host performances and lectures.

Black History Month is an annual celebration of achievements by African Americans and a time for recognizing their central role in U.S. history. Also known as African American History Month, the brainchild of noted historian Carter G. Woodson and other prominent African Americans. Since 1976, every U.S. president has officially designated the month of February as Black History Month. Other countries around the world, including Canada and the United Kingdom also designate a month to the celebration.

To join the celebration, the Americus Times Recorder will introduce three people who have been instrumental to our history or are bound to make our history all the richer. There is no doubt we will fall short in presenting a complete picture of these three, but it is our hope to give you a glimpse of these fine examples of humanity and what they mean to our community’s past, present and future.

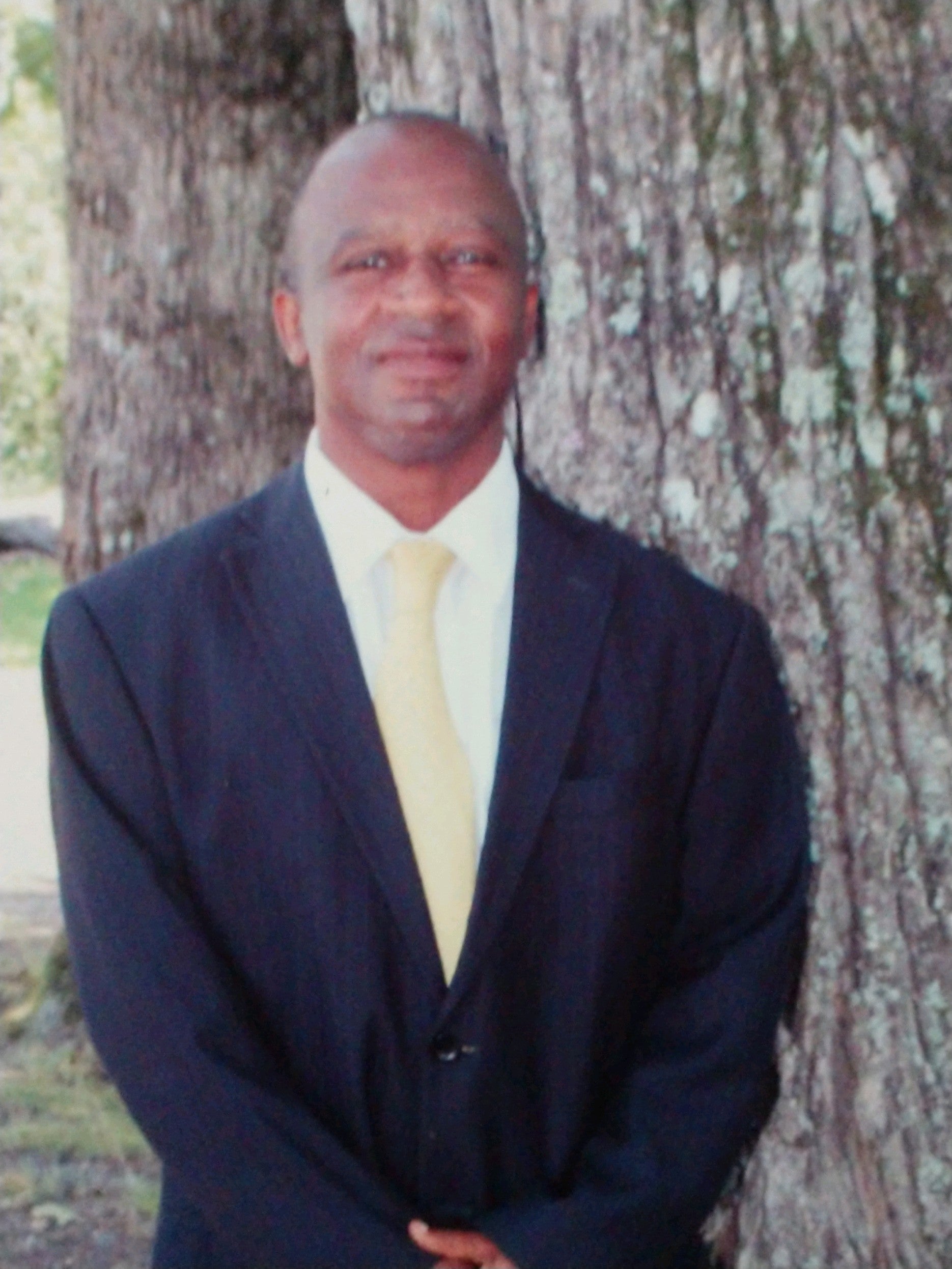

Marvin D. Harris

Marvin D. Harris is Sumter County born and raised. His is a well-loved face around the community and he can be found offering a helping hand day in and day out. He is especially passionate about the youth in our village and he works tirelessly to insure they are receiving the best out of life. Marvin is a proud graduate of The Sumter County Comprehensive High school and The Fort Valley State University. While at Fort Valley State University he joined Phi Beta Sigma and his loyalty to the fraternity’s brotherhood continues today.

Currently Marvin works for Middle Flint Behavioral Health as a Social Service Tech II. He works with those managing a mental health diagnosis as well as addictive disease diagnosis. He is well versed in case management as well as medical management skills. He holds tight to the philosophy Mohammad Ali put forth: “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on Earth.” Marvin is a man of service and it becomes quickly evident he reaps many rewards for investing himself in service to Sumter County. He is hasty in reporting “I believe I was placed on Earth to help others in need.”

Marvin also credits the neighborhood in which he grew up, Southerfield Heights, in teaching him about creating an involved community. He speaks of how families in the neighborhood would open their doors to each other and the parents would take responsibility for the children because they wanted the best for all their youth. Marvin reports the children would learn they were expected to perform well both at home, in school and in the neighborhood. The adults were consistent in providing leadership and should an issue arise, everyone was vested in making sure the child walked away with a valuable lesson. Looking after one another became a way of life and influenced Marvin in many ways.

In seeking out wisdom from his college advisor it became clear there was a lack of black men in the social service field. Marvin understands black boys in particular need to see solid leadership in black men, and he takes the responsibility of being a mentor seriously. He serves as a mentor for kids from 8 to 18, most of them boys. “They need to see a positive role model, if they don’t see one, they’ll see negative things. We encourage doing well in school, staying out of trouble and to do positive things even when people are not looking.” Marvin approaches the young men he serves at Middle Flint with a special compassion. He can tell stories of young boys coming in suffering from depression and suicidal idealization and how they overcame. One of these young boys began to involve himself with sports, made graduating a goal and is currently working on his doctorate degree. Marvin believes in the power of sports and the lessons they teach.

Marvin has been involved in little league sports at the recreation department for 25 years. He will pick up youth to play on the team, he will also return them home. He teaches a healthy respect of peers and the value of teamwork. Marvin says he witnesses teammates becoming friends, becoming more fit and their self-esteem rising. Just as important as pointing out successes, he lets his players feel the disappointment of poor behavior. If there is a breech in behavior, he will allow the youth to dress out, but they will be riding the bench for the game. “I let them dress and watch the team. I think he needs to see it. It’s easy to just stay home, I want him to see his teammates play.” Marvin reports that inevitably the call of the game will get through to a youth who has behaved poorly and motivate them to get back on the right path.

In addition to his coaching efforts, he also works hand in hand with his fraternity’s Sigma Beta Club. The club focuses on making sure youth see what is available to them if they are willing. Many times, the youth will come from an unhealthy environment but the men leading the Sigma Beta Club will expose them to positive things such as college fairs, trips, resources they might not have, motivational environments and military options. The youths served are 8 to 18 and usually African American males. The club offers mentorship and opportunities all year round and does not require an academic qualifier. Eligibility for the club comes when someone invests in the young man and nominates him for membership. Marvin can also be found at the Boy’s Club helping with efforts. He is quick to admit, “If we don’t get them young, the street is going to get them—gangs will give them attention.” Marvin practices a proactive approach in hopes that our youth will be successful from the beginning, learning how to become productive members in our village.

Although Marvin is highly active with our youth, he does significant work in adult activities as well. He serves as the President of the Americus Area Alumni Chapter of Fort Valley State University, on Phoebe Sumter Medical Center’s Patient and Family Advisory Council, Chairman of the Americus Walk of Fame Committee and as the Second Vice President of the Sumter County NAACP. As Second Vice President he is given the opportunity to assist someone whose rights might have been violated, but he is also on the Scholarship Committee which gives him the opportunity to assist in giving out scholarships to local students during the NAACP Freedom Fund Banquet. Marvin can also be found serving as a deacon for Welcome Baptist Church where his family has attended for generations.

When speaking of crime in the area, Marvin’s opinion is that “it is everybody’s problem. We got to take control of our own neighborhood, watch, observe, if you know a person tends to do wrong, you need to say something.” This is reminiscent of his days growing up in a neighborhood where the community at large helped in solving problems. Marvin likes to make an impact before a youth is 13. “That’s why I do what I do with young people. I hope the streets don’t get them because they are hard to get back.” One of the events he thinks was a good sign was recent marches in which both black and white came together. We need to talk, not yell, not disrespect, the goal is to respect everybody.” When asked what wisdom he would like to see Sumter County employ, he says, “Lets work together as one. Let’s see everybody work together, not just Americus, but also DeSoto, Leslie, Cobb, Andersonville—all the cities.” Marvin sees potential in our churches to help bring about a cooperative effort. “It starts with the church and church leadership. We need dialogue, for everybody to get on the same page.”

Marvin D. Harris is a good man to have on your page. He puts his feet to the ground in making change for the better happen. He has an ability to set a vision and follow through and his generosity of spirit is welcomed in Sumter County.

Teresa Mansfield

As with many teachers, Teresa Mansfield is best known by Ms. Mansfield. Ms. Mansfield has a rich story to tell and to hear her tell it, you will wish you had her for a teacher. You would have to earn your grade, she is not a believer in giving what is not deserved, but you would be happy to learn under her leadership. However, her story does not start with her teaching career. The story the Times-Recorder got to enjoy started in 1966. Teresa was born and raised in Americus and in 1966, Georgia Southwestern College (GSW) came looking for her. The president as well as a dean approached her to attend GSW. President King and Dean Teel offered her a scholarship, a grant and an opportunity to work 3 hours. “I jumped on that idea!” Ms. Mansfield reports. She classifies her family as “working poor” and the idea of having some financial incentives was incredibly attractive to her. She does however admit, “I didn’t think of the social implications, but that’s how I ended up there.”

The social implications would allow Teresa to grow into a well-loved teacher and person. Although there are some questions as to whether she was the first black student admitted to GSW. There is no doubt she was the first continuous black student to graduate from the college. From June of 1966 to December of 1969 Teresa dedicated herself to her education. Her family were believers in the power of education, so she was ready to invest in the days ahead. Teresa reports meeting her advisor who “looked shocked” to see a black girl enter the college. While she isn’t entirely certain how it happened, she ended up in a Physical Education class where square dancing was taught. She pondered, “Who is going to choose me to be their partner for square dancing? They frantically ran away from me. The P.E. instructor became my partner.” Teresa eventually dropped the class, stating “nobody wants to be a black girl’s partner.”

While she might not have been excited about a square-dancing class, she was excited about political science, and made it her major. She reports loving political stuff and she would spend a great deal of time reading the Americus Times-Recorder and the Atlanta Journal Constitution. “I read everything about government and history I could. I read constantly.” Her love of history would end up lingering throughout her life and she would enjoy teaching it as well as other classes such as life skills. Teresa reports she would sit in the middle of the class of fellow students with looks of “utter shock on their face let me know they hadn’t been forewarned”. She had not purchased her textbooks when a pop test was announced. She let a teacher know she didn’t have a textbook he instructed her to take the test anyway. Teresa made a 100 on the test because it was on current events and she had read everything she could on the world around her. When she received that 100, the teacher admitted to her that he was prejudice, “but I gave you the right grade.” The same teacher would also openly admit he didn’t like blacks in class. Speaking with Teresa, she doesn’t linger on those painful times, she quickly turns to something she did love—working in the library. “I love the library and I love to read. I was surrounded by books and magazines I’d never been able to see before.” While working the circulation desk, the professor who would readily admit he didn’t care for blacks, came to her and asked how she was doing. In Teresa’s mind, she questions, “maybe that is his way of becoming more compassionate by asking me how I was doing.” Ms. Mansfield has some sweet memories of her days at GSW, but she also remembers wanting to run to her mama who worked two blocks away. As much as she wanted to, she never did because she knew that would cause her mama to experience stress, and being an asthmatic, Teresa didn’t want to risk her mama’s physical health. Teresa kept pushing through until she finished her student teaching requirement. Two days after completing the student teaching, Staley High School hired her and she was given her own class. Staley was a black high school in those years and Teresa quickly put her skills to work. Even as a brand-new teacher, she says, “I had command of the class, I didn’t have discipline problems, they knew I was no-nonsense.” In 1970, Ms. Mansfield would make a move to Americus High as it was being formally integrated.

Teresa reports those days as “very contentious but I learned how to deal with it.” She was often called to the office to address some student issues but also to address parents who felt she did not give their child the correct grade. Eleven black teachers came to Americus High School (AHS) that year. She had some students who she wonders about still. She can remember them being “vicious because of the color of my skin. And it only takes two or three to ruin a class.” Ms. Mansfield would learn rather quickly how to tread those waters. “I learned to rise above. Some will have disdain, no matter what. But I was prepared and knowledgeable. I am not going around with my head hanging low like a wounded dog. I had to psych myself up every day. I knew I would hear the “N” word, but I would not acknowledge it.”

Ms. Mansfield, although serious about the students learning, also showed a very compassionate side. Students who were dismissed as unable to learn found themselves thriving in her classroom. She reports showing an interest and an ability to care about a student will go far in seeing their performance bloom. Some students, she readily admits, she didn’t know were considered “special ed” students and she was surprised to hear of this because they had done so well in her class. While there were some students who would never accept a black teacher, Teresa also reports many would. She celebrates both types of students and worked diligently with all of her students. Parents would also present problems from time to time. Teresa stood her ground in delivering grades. There was no special treatment, and her grading was honest and not to be influenced by parent or teacher pressure. Her integrity was something she cherished, and she made sure she was doing the best she could by every student. However, some students would demand more understanding. There are the heartbreaking stories of students coming from difficult homes and this manifesting in the classroom. Ms. Mansfield would make special efforts to reach them because she could see the potential in them. There was one student who consistently refused to bring his textbook to school. After Teresa provided enough persuasion, he finally did, but he put it under his desk. After investigating this situation, she realized, “if he didn’t have a book, then he wouldn’t have to be embarrassed when he couldn’t read.” Ms. Mansfield would take students such as this young man and pour extra into them. Sometimes though, it wouldn’t be enough, and the students would be put out of school.

Teresa would eventually retire as a beloved teacher after serving over 3 decades. She has seen her share of frustrations, but she speaks most loudly on the successes. “I like to reflect on good black kids and good white kids. You can’t reach them all, but you can reach some.” Teresa is still in love with reading and shares her love of books with others. She has given away 50,000 books and has no intentions of stopping. While COVID-19 has slowed her down a bit, she will be back out there reaching our community through her passions. Another passion are all the kids she claims. Some are family, some are godchildren, and some are students. She is always delighted when her students refer to her as a mother or having raised them. She sees a lot of her own parents in that, because they too provided a place where children enjoyed being.

Teresa Mansfield is a powerful testimony to focus, determination and compassion. She has seen the stories of many lives unfold before her and she has invested in those lives. Sumter County is proud to call her our own.

Carl Reid, III

Carl Reid, III came to Americus in 2000. He comes to us by way of Bloomfield, Connecticut, which he credits with blessing him “by molding my thought processes where humanity is concerned.” Carl reports he grew up in a diverse neighborhood where every child of every color was welcomed into the homes of Bloomfield with open arms. “Parents knew each child’s name. We were a mixture from every place in the world and we were all brothers and sisters.” Carl brought this approach of inclusion to Americus and began his career in the District Attorney’s office as a Victims Advocate where he worked on behalf of victims by ensuring all the resources available to them were known. Carl says of himself, “I am a soldier of humanity—for anybody who needs help because as a fellow human it is my obligation to help them overcome what they are going through.”

Carl knows what is means to overcome. As a recovering addict, he has been on the receiving end of others who knew how to reach him and be with him on his journey to sobriety. After a relapse, he entered treatment here in Americus and eventually was employed by that same treatment center. Currently he stands beside other addicts who are in different stages of recovery as a Certified Peer Specialist (CPS). Being involved in a CPS driven program is a unique approach to mental health and addiction as all the CPS staff have shown a proven ability to overcome or manage a mental health or addiction related issue. Carl along with 2 others carved out a place where they can practice being “soldiers of humanity.” The Social Exchange was born in January of 2019 and their mission is not limited to offering aid to those who need a warrior beside them as they begin their healing.

Carl is passionate about bringing a place of healing to the community at large. He is a big believer in community and adamantly believes in carving out a space where folks of different colors, backgrounds and beliefs can begin to understand and appreciate each other. Carl was influenced by his home in Bloomfield, but he also credits his service to the Black Student Union (BSU) during his college years as well. Carl served as president of BSU for 4 years. He left his mark on the position by not limiting himself to just black students. He wanted to reach the whole student body and he did so by emphasizing every voice who came to the table. Carl insures there is room at the table for all voices, and he believes in the power of communication and empathy to create healthy communities.

There have been some contentious times in our recent history and there is a thirst to find connection among us. Carl is aware that carrying around resentments and feeling isolated by labels is a tough burden to carry. Carl has a very simple philosophy to address this very human feeling. He once again opens a table and invites those who would like to be heard to have a seat. He honors, encourages and even hopes for differing opinions, but while he gives a standing invitation, he also facilitates a place where understanding can grow. Understanding a person’s story or even their point of view is not necessarily agreeing with it, but there is respect, power and healing in the simple gift of understanding. The Social Exchange keeps this as a primary goal.

The Social Exchange focuses on our strengths as a community. They see an arts district as bringing great potential to our home. They see treating not only those who are overcoming mental health and addiction issues as a priority they see the importance of our neighbors sitting down with each other to seek out understanding as a priority. Carl wants it known The Social Exchange is not a political movement. The Social Exchange is a “social movement for the betterment of humanity.” While finding common ground even in these most contentious of political times can seem an overwhelming task, The Social Exchange does not endorse any political movement. What they do endorse is a healthy community which Carl believes starts with simple conversation.

Ask Carl what his day looks like and he describes starting the day out with prayer and meditation, which is vital for those in recovery. He then goes about addressing making our community richer by creating a space for folks of all types to find a place to belong. Currently there is work to be done in creating an arts district. There is effort put into securing grants which will better our neighborhood. The work continues in bringing free Wi-Fi services to the area. Carl likes the idea of folks getting off the Jackson Train Depot and being able to utilize the Wi-Fi. He also welcomes students to come find a place off campus where they can enjoy a place of connection. In addition to the work the Social Exchange is doing, Carl is also a poet. He has three manuscripts and some of his work can be found in the Library of Congress. He puts his heart and soul into his writing as they are his personal story. At one time, he was given an opportunity to publish more work, but he stepped away because he wanted to hold on to his precious stories and exchanging them for money was not appealing to him.

When asked to sum up his approach to make a richer community, he agreed that “connection through education and empathy” is his thing. Carl admits it can be a lonely mission and even at times he gets rejected for holding out hope it can happen. However, Carl keeps going forward, one day at a time to make his impact on history. For such an optimistic, hopeful and open-minded approach, Sumter County will surely prosper.

*Historical facts on Black History Month and its origins was found on History.com. The article was originally written on January 14, 2010 and was updated on January 28, 2021. Further reading can be found on the website under the topic of Black History Month.