Carved in Americus: One Confederate Ring

Published 10:55 am Wednesday, March 24, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Evan A. Kutzler

An early visitor to the Confederate Museum (now the American Civil War Museum) in Richmond, Virginia, first entered a “Solid South” room that served as “a representation of the whole Confederacy.” Past this reception room, each of the eleven states in the former Confederacy—as well as Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri that never seceded—curated their own exhibit space. The Georgia room sat on the first floor and to the right of the Solid South room.

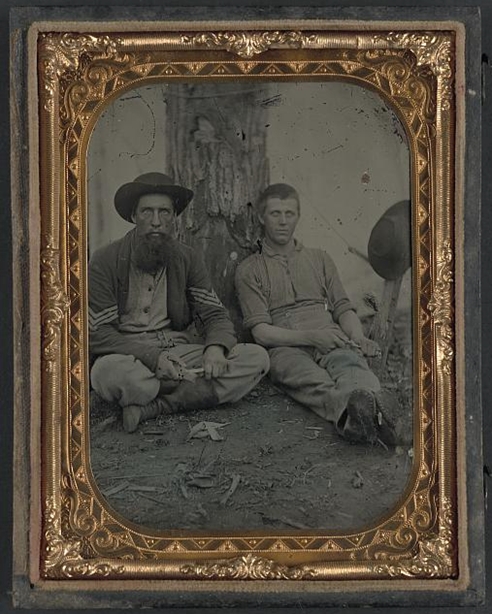

The collection of “relics,” as they were called, underscored the symbolism that made the museum a semi-religious repository and an ideological shrine. Alongside books, photographs, and uniforms, the Georgia room exhibited a scrap cut from Robert E. Lee’s tent and a piece of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s desk. Many relics came from the mothers and daughters of Confederate soldiers. From Americus, Georgia, Amelia Barlow Lester donated her son’s frock coat, vest, and pants that she—or, in all likelihood, an enslaved woman—made for him. Other Americus items included an ambrotype of Adam Robinson, John M. Coker’s canteen, and the sword carried by Samuel Dawson. One shelf in the Georgia room held a pair of rings: one carved by a Confederate prisoner and one made by a soldier in an Americus hospital.

The catalog description left important questions unanswered. Donated to the Confederate Museum in 1898, the cataloger recorded neither the maker’s name nor the name of the donor. The ring is plain, smooth, and still shows markings of a tool used to file it down. It does not appear to be animal bone or wood. If a soldier carved it from a button, as the current collection description indicates, it might be a “composition” button of resin and various materials manufactured by companies such as Goodyear and commonly called “India rubber” or “gutta-percha.” As with the Confederate Museum’s receiving room, the ring takes us into a wartime culture of carving and gifting that stretched from hospitals to prisons and across the hazy line separating the front line and the home front. It is also a rare reminder of the hospitals in Americus in 1864 and 1865.

Carving in the Civil War

Carving in the Civil War, like the conflict itself, destroyed and created. While the citizens who went to war in 1861 had much to learn about soldiering, many brought whittling skills from home. They carved up everything. Confederate soldiers turned oval “U.S.” belt plates into “C.S.” buckles with a penknife. Soldiers on both sides whittled lead bullets into game pieces, figurines, fishing sinkers and everything in-between. They carved briarwood pipes for smoking tobacco and made jewelry from bone or gutta percha buttons. Carving transformed refuse or natural material into ornamental keepsakes that displayed the ingenuity and hand skills of the whittler. It created “relics” out of day-to-day objects and everyday experiences.

This artwork represented, in part, a response to boredom. Yet curator and historian Lea Lane argues that this explanation trivializes a widespread form of artistic expression in the Civil War era. Carving served practical, emotional, and social purposes. Whittling kept soldiers warm because wooden shavings made fire starters in landscapes stripped of kindling. The products expressed individuality in a war that threatened to erase it. Soldiers carved their names into trees, building walls, rocks—even the Washington Monument. With a needle and ink, some soldiers carved their names into their bodies to avoid an “unknown” grave. Carving was cheaper and, considering the number of illiterate and barely literate soldiers, more democratic than journaling or letter writing. As a communal activity, carving cultivated fraternal relationships among carvers. Giving rings extended relationships not only between men and women but also between men.

Bone, wood, and gutta percha rings became popular pieces of jewelry that Union and Confederate soldiers exchanged within prisons, sold to guards, or gifted to civilians who provided material support. According to historian Annelle Brunson, giving and receiving a Confederate prison ring between men and women could carry several meanings. Giving rings used Christian values of reciprocity to strengthen relationships. Wearing a Confederate ring displayed partisan support. In other words, giving or receiving a carved ring did not necessarily constitute a romantic or, at least, an exclusively romantic relationship. Soldiers gave rings to civilians in exchange for food and supplies and Confederate women often collected rings from multiple men. These rings become keepsakes and collectables in the decades after the war.

The Americus Hospitals

The museum’s ring, an example Civil War carving culture, also reveals something about the experience of Confederate hospitals in Americus. Similar to northern prisons, the Americus hospital blurred the lines between combatant and civilian, humanitarian and partisan support. Patients relied on both professional and volunteer support. In the context of privation, making and giving a ring to someone who offered invaluable support may have helped to preserve a soldier’s sense of manhood and dignity.

Wounded soldiers, physicians, and nurses arrived in Americus in the summer of 1864 as Confederate hospitals evacuated from the Atlanta area. The arrival of Confederate soldiers put additional strain on regional resources. After all, there were more than 30,000 sick and hungry Union prisoners only twelve miles away at Andersonville. Local women who sent provisions to the Confederate guards at Andersonville quickly extended support to patients. Ring exchanges may have come as a direct response to the work of a local aid society.

Kate Cumming, a nurse with the Army of Tennessee, arrived at Americus on August 19, 1864. “We can not tell how we shall like the place,” she confessed. “It is quite a large village, and from all appearances we are going to have a very nice hospital, but none of us liked being compelled to come to it.” The air felt too hot and the move did not bode well for the fate of Atlanta. Cumming also questioned whether the Americus gentry had provided enough to the war effort. She described the city as a “wealthy place” and remarked “were we to judge from the carriages and fine horses we see, I should think the impressing officer had not been down this way in some time.”

Hospitals covered Americus for months. The Foard Hospital set up in downtown buildings. Tents for gangrene patients covered the public square. Cumming wrote, “One lad suffers so much we can hear him scream for two squares off.” The Bragg Hospital occupied the Furlow Masonic Female College on the southside of town and other hospitals set up tents near the South Western Railroad Depot on the north side of town. An eye ward stayed behind when other hospitals moved again in the late fall of 1864.

Disaster increased the burden on local women and the proximity of patients and civilians. On August 31, 1864, a fire started in a cotton warehouse and spread to cover two city blocks. While there were no reported casualties, the blaze destroyed 27 buildings, including the hospitals along Jackson Street. Newspapers reported that an enslaved African American teenager, assigned to work at the hospital, set the blaze when he discarded a match after lighting a pipe. Rumors suggested sabotage, but the newspapers, the military, and Cumming all declared it an accident. Displaced patients moved to other commercial buildings, tents, and the homes of Americus residents. Increased points of contact made ring exchanges more likely.

At the Confederate Museum

It is not clear why the owner of the ring donated it to the Confederate Museum. The museum displayed a large number of carved items, including a large number of prison rings from Point Lookout, Johnson’s Island, Elmira. Many of these items preserved only the name of the maker, the name of the receiver, or the place of production. These “relics,” like the rest of the collection, romanticized the Confederate soldier. A visitor might imagine the carved ring as a homespun marriage proposal. It became harder to remember it as a form of currency, a symbol of partisan support, or a show of gratitude from someone with nothing else to give.

The ring is also one of the last physical reminders of Confederate hospitals in Americus. Almost all of the downtown buildings that could have been used are gone. Late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century buildings, including the Windsor Hotel, replaced the city’s public square. Only the cornerstone of the female college remains. Victorian homes replaced most of the antebellum houses. The ring carries the culture of carving in the Civil War era, the men and women who worked in Americus hospitals, and wartime reciprocal relationships in camps, prisons, and hospitals. It may not matter that its full personal history is lost. From trash to keepsake, the ring was a common enough item and a common enough gift to have been made by any Confederate soldier and given to any white Americus man or woman. It represented the human connections on a Confederate nation.