Billy Proctor’s Appeal

Published 4:27 pm Friday, June 18, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Evan Kutzler

On December 1, 1854, Billy Proctor asked a powerful enslaver to purchase him. “Sir,” Proctor wrote, “As my owner, Mr. Chapman[,] has determined to dispose of all his Painters, I would prefer to have you buy me to any other man. And I am anxious to get you to do so if you will.” The skilled painter anchored his request on his reputation among white men and slaveowners in a delicate attempt to shape his future. “You know me very well yourself,” he told John B. Lamar, “but as I wish you to be fully satisfied, I beg leave to refer you to Mr Nathan C Monroe Dr. Strohecker and Mr Bogg.” Beginning with the verb, “dispose,” Proctor underscored his trauma and the urgency of his request. “I am in distress at this time, and will be until I hear from you what you will do.”

Billy Proctor’s unusual and risky appeal came at a specific moment in the history of Americus. The arrival of the South-Western Railroad that year turned Americus from a courthouse town into a small city. Charles Hancock, editor of the Sumter Republican, chronicled the changes. “What an impulse will be given to matters in Americus,” he wrote in early 1854. “Old buildings will revive, vacant lots will be occupied, stores multiply, and general industry ply her wheel more vigorously than ever.” The sights and sounds of hammers, saws, builders, and painters continued all spring and summer in anticipation of a railroad connection that fall. “The mechanic is to be seen busily plying the implements of his profession, and every breeze wafts to the ear the hum of industry and enterprise,” Hancock wrote. “In every direction private residences are in process of erection. Besides the private residences, a number of new business houses are going up.”

Somewhere in that wafting hum was Billy Proctor and what sounded like music to Hancock was, in part, a sound of slavery. These sounds became more common in the 1850s as demographics shifted. In 1840, 72% of Sumter County’s 5,759 residents were free, but the arrival of enslaved people outpaced free people for the next two decades. By the eve of the Civil War, 52% of Sumter County’s 9,428 residents were enslaved. This was not an anomaly. In places like southwest Georgia, slavery became more common than freedom. Rich men like Lamar, who owned 200 people in Sumter County in the 1850s, first imagined the region’s transformation into the Cotton Kingdom and then made it so.

The rare letter is remarkable in many ways. First, when it is laid side by side with other letters, one learns that Billy Proctor was more literate than the white overseers who managed John B. Lamar’s plantations. Second, the preservation of the letter is nothing short of a miracle. Proctor’s voice endures into the present. And while he wrote to a specific audience, his voice does not come filtered through the writings of slaveowners.

The letter also highlights an important distinction within the vast experience of enslaved people. Proctor worked under the “hiring-out” system, a euphemism for a practice of renting enslaved labor, skills, and knowledge. Slaveowners leased out men, women, and children for specific jobs or for a set period of time. Across the U.S. South, hired-out enslaved people worked at colleges and universities, in factories, on docks, and in just about every skilled industry. It was not a better experience than the plantation, but it was a different one.

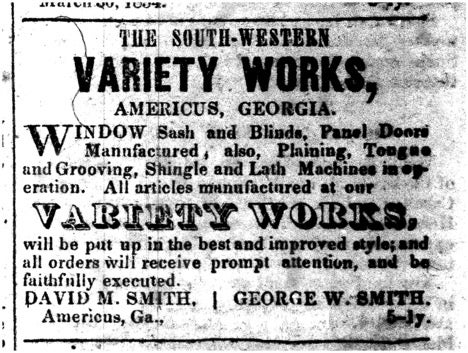

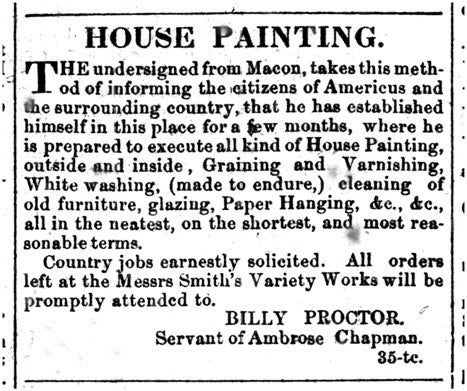

The hiring out system took Billy Proctor from Macon to Americus. On October 26, 1854, an advertisement appeared in the Sumter Republican. “The undersigned from Macon, takes this method of informing the citizens of Americus and the surrounding country, that he has established himself in this place for a few months,” Proctor wrote, “where he is prepared to execute all kind of House Painting, outside and inside, Graining and Varnishing, White washing, (made to endure,) cleaning of old furniture, glazing, Paper Hanging, &c., &c., all in the neatest, on the shortest, and most reasonable terms.” Based in the growing city, Proctor appealed for “country jobs.” He asked readers to reach him through George W. or David M. Smith, who owned the South-Western Variety Works and had likely rented Proctor.

The names of white men, including his owner Ambrose Chapman, flesh out part of Billy Proctor’s network. Born in North Carolina, Chapman owned 43 people in Monroe County in 1850. Over the next decade, he moved to Bibb County and, as Proctor had warned in 1854, downsized his estate. On the eve of the U.S. Civil War, Chapman owned 14 people whose names are not known at this time. Nathan Monroe, born in New York, was a banker in Bibb County who owned 7 enslaved people in 1850. Dr. Edward L. Strohecker, a physician and graduate of the Medical College of South Carolina, also lived and worked in Macon. The connection between Proctor and these men, most of them slaveowners, was unclear. Had he painted their houses? Or had Chapman in years past rented Proctor out in the banking and medical industry in Macon?

After listing the three references, Billy Proctor turned to the terms of sale. Chapman wanted $1000 for him, but Proctor told Lamar that his enslaver might accept $50 less than asking price. He continued, “Now Mas John, I want to be plain and honest with you. If you will buy me I will pay you $600 – per year untill this money is paid, or at any rate will pay for myself in two years.” In other words, Proctor promised the investment would pay off in less than two years. Proctor knew the other desires of a potential buyer as well. He could not prevent being sold, but he seemed to know that his outward disposition, alongside his physical health, shaped his value and might shape his future. “Mr. C wants me to go where I would be satisfied, – I promise you to serve you faithfully and I know that I am as sound and healthy as any one you can find.”

Billy Proctor only hinted at his reasons for writing specifically to Lamar. “I am fearfull that if you do not buy me,” he wrote, “there is no telling where I may have to go.” Was Proctor trying to avoid being sold to some far-off plantation? Did he want to keep some day-to-day space from his owner that came with the hiring-out system? Was he trying to return to the vicinity of Macon where he likely had family? Some private knowledge that we do not know lay behind the words “anxious,” “fearful,” “distress,” and “trouble.”

The letter ended with risks. Proctor asked Lamar for both a personal favor and for a white man to keep an enslaved person’s secret. “You will confer a great favour sir, by Granting my request, and I would be very glad to hear from you in regard to the matter at your earliest convenience,” Proctor wrote. “I would rather you would not say anything to Mr. C- about this matter untill I can hear from you, for I assure you I am in great distress and trouble at this time, but if you will grant my request – you will please write me a few lines, and I will come immediately to Macon to see you.” In concluding the letter, “your obedient & Humble servant,” Proctor reversed a traditional valediction between free people for the unique situation of and enslaved man writing an enslaver. It performed obedience and reiterated his earlier promises.

We do not know what happened to Billy Proctor. Proctor’s unusual and risky appeal, alongside his newspaper advertisement, are the only currently known records of his life. We do know that Lamar and, later, Lamar’s family kept the letter. In this way, it was not a “new” find or “discovery.” It was first published in Plantation and Frontier Documents, a collection edited by Ulrich B. Philips, more than a century ago, under the section title, “Slaves’ Purchase of Freedom.” At the time, the original letter came from the family papers of Mary Ann Lamar Cobb Erwin. She was a prominent member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the wife of a Confederate officer, Alexander S. Ewrin. Why had she kept it?

As with all historical records, each generation of readers comes to the past with a different frame of reference and new questions. For white historians in the early twentieth century, the letter suggested Lamar’s benevolence. Not so today. The letter remains though an important document on the difficult subject of slavery. Proctor’s appeal is captivating because he does not easily fit a mold. What Proctor says—and what he does not say—provokes questions that have no clear answers. In asking questions of the document, readers reckon with Proctor’s trauma and the ways and enslaved man attempted to shape the next phase of his life.