Civil Rights and a Lived Theology in a Southern Town

Published 2:12 pm Wednesday, January 19, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

January 13, 2022

Evan Kutzler

Note: A version of this review was published on H-Net in April 20, 2021, https://networks.h-net.org/node/11465/reviews/7596927/kutzler-quiros-god-us-lived-theology-and-freedom-struggle-americus. It is reprinted with permission.

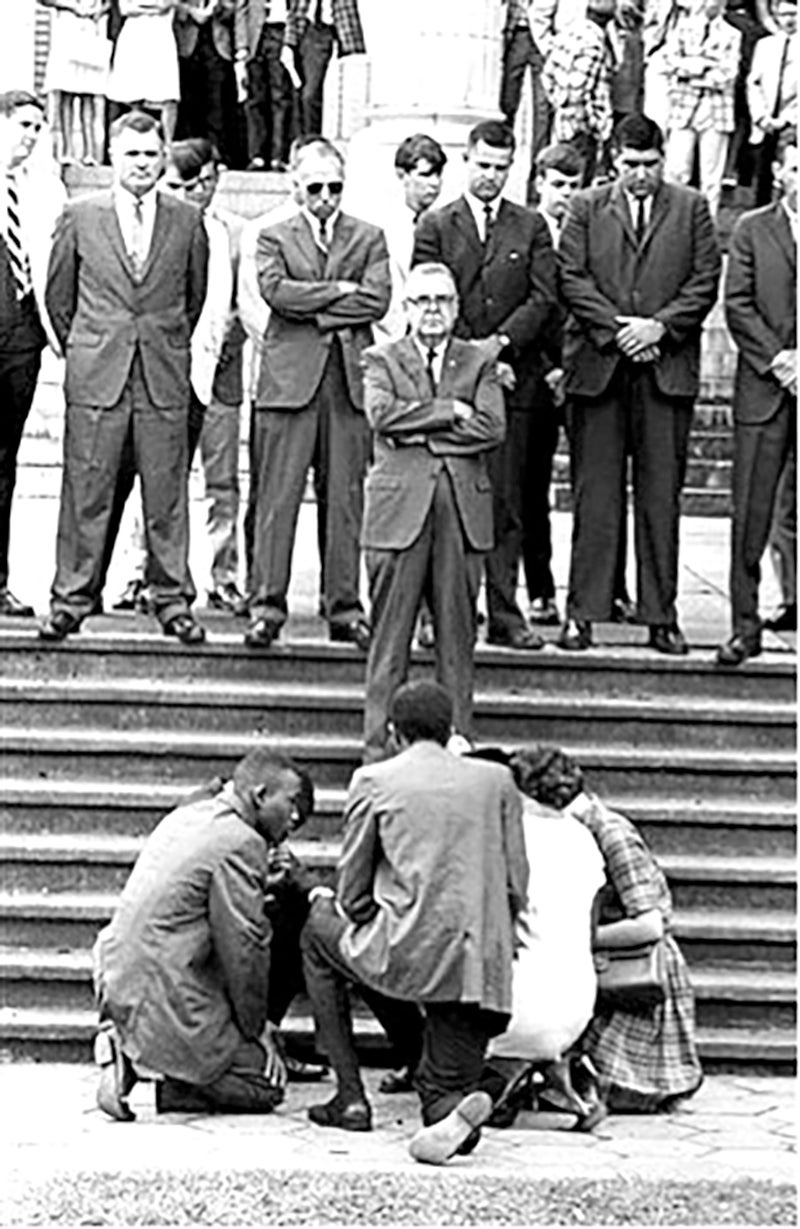

The tension in the photograph taken outside the First Methodist Church (now the First United Methodist Church) on Sunday, August 1, 1965 is gripping. At the bottom of the steps, six teenagers huddle together, kneeling in prayer on the hexagonal paving stones that still line the public sidewalk. Above the kneelers on the fifth step stands a frowning man in a dark suit, his arms folded, staring directly into the camera. Behind him stand a line of men in suits on the landing followed by teenagers in light jackets. Their faces all show various levels of determination not to let anyone climb the stairs and disapproval of the prayer circle below. At the top of the stairs, a mixed group of white men, women, and children stand at the base of the church’s massive Corinthian columns.

Protestors “knee-in” at the First Methodist Church, August 1, 1965, Associated Press.

University of North Carolina Press, 2018

The gripping photograph captures the central conflict in Ansley Quiros’s book, God with Us: Lived Theology and the Freedom Struggle in Americus, Georgia, 1942-1976. Quiros tells us, “For many this photo represented the hypocrisy of Southern Christianity and race relations; for others, it represented a courageous stand against a ‘heretical culture,’ and for us, it represents the theological stakes of the civil rights movement” (151). Framing the national civil rights movement as a religious conflict, Quiros takes readers through the “lived theology” of activists and their opponents in Americus Movement and beyond. Lived theology, Quiros explains, “is the story people tell themselves and others about what God is doing in the world and how they are participating in that divine action” (6). In a book steeped in historical empathy, the religious beliefs of the gatekeepers are as important to Quiros as those arrested on the sidewalk below for disturbing the peace and interrupting church.

The focal point of God with Us is Americus. The city, its county, and the region all have rich and difficult histories. Straddling the northern border of the county was Camp Sumter, a Confederate prison in the U.S. Civil War where 13,000 U.S soldiers perished for want of wholesome food, clean water, and shelter in 1864-65. In Plains, along the county’s western border, Jimmy Carter became the first (future) president born in a hospital in 1924. Until November 2019, he taught Sunday School for decades to anyone who showed up at the doors. In the southern part of the county, Clarence Jordan founded an interracial Christian farm in 1942 that became the birthplace of Koinonia Partners, a partnership housing program, and, later, Habitat for Humanity.

While the geographical footprint of God with Us is small, its central idea has implications for the broader civil rights movement. Historians, Quiros tells us, have downplayed the religious conviction of civil rights activists and their opponents. “The civil rights struggle, rightly understood as a major social, cultural, and political conflict,” Quiros contends, “constituted a theological conflict as well” (2).

Koinonia became the first battle in the local iteration of this religious conflict. The farm was “theologically orthodox but socially radical,” Quiros explains, and the Koinonians set out to “restore creation” through good farming, build a Christian community that shared property and redistributed wealth, and erase the “man-made hierarchy” of race in the South (24-25). Although seen by local whites as outsiders from its beginning, the threats, the shootings, the bombings, and the boycotts of Koinonia began after Brown v. Board of Education. “Koinonia Farm was a voice crying in the wilderness,” Quiros asserts, “a prophetic John the Baptist that preceded the civil rights movement in Americus and offered a foretaste of what was to follow: a bitter theological struggle over race and religion” (40). The ostracism and boycotting of one devout Christian community by other devout Christians continued for years. Even Jimmy Carter did not go to Koinonia.

Perhaps the most unique feature of God with Us is the empathy Quiros extends to Christians who opposed the civil rights movement. Quiros reminds us that most white protestants in the South “did not consider segregation incompatible with Christian belief” and they “envisioned themselves and their churches as guardians of traditional orthodoxy against the grain of an increasingly apostate America” (42). These Christians valued local control of congregations and saw national and international ruling organizations as political and religious threats. “The struggle against integration in the South,” Quiros writes, “became part of a larger struggle against liberalism, communism, and heresy, a struggle over the fundamentals of Christianity and for the soul of America” (48). Quiros’s careful treatment of these beliefs as sincere—not some political sleight of hand or false consciousness—is a strength of the book.

Distinct from the Koinonia “orthodoxy” and the “Lee Street theology” was the local incarnation of a “distinct Black theology” passed on from generations of enslaved Christians. This Black theology contained four tenets: all humans have dignity; racism is idolatry; God delivers freedom for the oppressed; and an “orthodox Christianity” in which Jesus was both Jewish and immortal. It also created a plan for action. “While many white Christians conveniently concluded that obedience to Christ would passively, even automatically, result in improved social relations,” Quiros writes, “black leaders asserted that obedience to Christ demanded active, intentional attention to social relations, namely racism” (63). These tenets, combined with Gandhian nonviolence, formed the organizational identity of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Prayer and song became key theological methods and expressions of civil rights organizers from the streets of Americus to chain gangs and the Lee County Stockade.

The standoff in front of the First Methodist Church marked an intensification of the religious conflict. The kneel-in occurred the Sunday after two Black men shot and killed Andrew Whatley, a white teenager, near an intersection where local whites harassed civil rights marchers. The kneel-in also took place only a half-block away from Whatley’s house. In Quiros’s telling, neither the victim nor his killers had any involvement in the civil rights movement. Yet the murder, coming two weeks before the Watts Riots in Los Angeles, gave fodder to the activists’ opponents. As Quiros explains, “They could peddle the notion of black people as inherently threatening, they could accuse protestors of being uncontrolled, and most significantly, they could assert that the movement was not really nonviolent nor was it Christian” (120).

Although Americus churches adopted closed-door policies at different times, the standoff in 1965 reflected a coalescing opposition to the civil rights movement. For millions of people who saw the photograph of the First Methodist Church, the standoff “constituted the most stark, embodied confrontation between the Christianity of Christ and the segregated churches of religious hypocrisy” (146). Yet the view from the steps was no less sincere and no less based in religious belief. For many white protestants in Americus, Quiros argues, “the kneel-ins represented the defilement of sacred space and the exploitation of pure religion for political and theologically suspect ends” (146). Defending a local church from integration—and control from ecclesiastical governing bodies—had become equivalent to protecting the sanctity of church defending the Bible as the word of God.

The standoff at the steps of the First Methodist Church was only part of the renewed push against civil rights demonstrations. The majority of whites in Americus did not confront civil rights activists in the streets or at church doors. “They asked for the preservation of law and order,” Quiros writes. “They stayed home. They whispered among themselves and challenged the morality of the movement, ostracized white dissidents, and formed private Christian schools” (139). White dissenters, including city attorney Warren Fortson and Georgia Southwestern College president Lloyd Moll, found themselves forced to leave their jobs, their homes, and their city.

Race, religion, and schooling also became increasingly difficult to disentangle. By 1965, an effort was underway to protect opponents’ theological and racial views through private, segregated Christian schools. Quiros argues that Engle v. Vitale (outlawing school prayer) was as important to the founding of so-called segregation academies as Brown. The fight to preserve white churches paralleled the struggle to keep prayer in public schools. “Instead of preaching salvation through Christ, people were preaching civil rights and voting,” Quiros writes. “This amounted to heresy” (139). Southland Academy emerged to protect intertwined racial and theological beliefs.

One of the values of microhistory is that it allows historians to have almost surgical precision. The challenge is that it is very easy for that scalpel to slip and patterns of errors (names, places, directions, etc.) can—for a local reader at least—undercut confidence and distract from a compelling thesis. Yet as God with Us shows, the reward is worth the risk. Quiros offers a fascinating history of an important place in the civil rights movement with a remarkable degree of understanding for the people—all of the people—wrapped up in religious struggle over race, religion, and human dignity.