Should texts, e-mail, tweets and Facebook posts the be new fingerprints in court?

Published 12:30 pm Saturday, February 28, 2015

WASHINGTON — In an episode of the CBS show “Criminal Minds” that aired last year, an FBI team is on a frantic hunt for a missing 4-year-old.

The team soon realizes that the girl has been given away by a relative, Sue, and that there’s no way Sue is going to reveal her whereabouts.

A crucial break comes when FBI profiler Alex Blake puts her “word wisdom” to work. Blake, who is also a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University, notices that Sue uses an unusual turn of phrase during an interview and in a written statement: “I put the light bug on.”

The FBI team launches an Internet search and soon discovers the same misuse of “light bug” for “light bulb” in an underground adoption forum: “I’ll switch the light bug off in the car so no one will see.”

Same author, right? On that assumption, the team springs into action and — bingo! — the missing child is found.

Inspiration for Blake’s expertise came from former FBI special agent and linguist James R. Fitzgerald, who became an adviser to “Criminal Minds” in 2008. Blake, he says, is a combination of him and his fiancee, Georgetown associate linguistics professor Natalie Schilling.

The incident, Fitzgerald says, is based on a 2008 homicide case, State of Alabama v. Earnest Stokes. In a linguistic report he prepared for the prosecution, Fitzgerald said he found the term “light bug” in an anonymous letter attempting to lead investigators off the track (“His (sic) had busted the light bug hanging down”) and in a tape-recording of suspect Earnest Ted Stokes. That was one of the lexical clues leading Fitzgerald to “opine” “with a likelihood bordering on certainty” that Stokes was the author of the unsigned letter.

“The (‘Criminal Minds’) writers love these real-life examples,” Fitzgerald explains in an email.

That’s not surprising. As more of our communication is written, the linguistic fingerprints we leave provide enticing clues for investigators, contributing to the small but influential field of forensic linguistics and its controversial subspecialty, author identification.

The new whodunit is all about “who wrote it.”

—

Answering that question becomes ever more urgent as we create a virtual trove of data — in email, in texts and in tweets that are often anonymous or written under pseudonyms. Private companies want to find out which disgruntled employee has been posting bad stuff about the boss online. Police and prosecutors seek help figuring out who wrote a threatening email or whether a suicide note was a forgery. A groundbreaking murder case in Britain was decided after a linguistic analysis suggested that text messages sent from a young woman’s phone after she went missing were more likely to have been written by her killer than by her. And in Johnson County, Tennessee, the outcome of the April “Facebook murders” trial may well hang, according to Assistant District Attorney General Dennis D. Brooks, on whether a linguist can convince jurors of the authorship of a slew of emails soliciting murder that were written, he says, under a fictitious name.

Textual sleuths find clues not in fingerprints or handwriting, but in word choice, spelling, punctuation, character sequences and in subtle (and usually subconscious) patterns of sentence structure. The sleuths have sprung into sight in recent years with such pop-culture stunts as identifying the author of “The Cuckoo’s Calling” (J.K. Rowling) and joining last year’s hunt for the bitcoin founder.

But as language specialists enter the legal world, they find the stakes are high, the science uncertain and the scrutiny intense. Take the cautionary tale of Don Foster, the English professor turned temporary gumshoe from Vassar College who documents in “Author Unknown” his transition from the comforts of academia to criminal investigations and the constant pressures of media exposure. Foster made headlines for connecting a funeral elegy with Shakespeare (he graciously recanted when subsequent scholarship suggested a different author) and for fingering Joe Klein as the author of “Primary Colors.” He went on to such high-profile cases as the Unabomber and JonBenet Ramsey investigations and was sued for defamation by Steven Hatfill after writing a Vanity Fair article that, the suit alleged, implicated the scientist in the 2001 anthrax mailings. (The case was settled out of court.) Foster said in an email that he deeply regrets “ever having waded in(to) the minefield of examining documents” and having faced, as an expert witness, adverse parties who “introduced material dredged up on the Internet.”

“There are disputes about the acceptability” of linguistic evidence in court, says Lawrence Solan, a professor of law at Brooklyn Law School who served as president of the 175-member International Association of Forensic Linguists. The sometimes acrimonious controversy, he explains, hinges on the state of the science — whether linguists can provide reliable statistics on their accuracy or “error rate.” Solan describes an “intellectual and cultural divide” between practitioners such as Fitzgerald who use what he calls an “intuitive” approach, examining among other things idiosyncrasies in spelling and word choice to see whether “constellations of features emerge”; and computer scientists, who perform statistical analyses of such features as character sequences or word length, often by running large amounts of text through software programs. Solan hopes a convergence of those methods might provide sounder science.

Neither technique is any good, according to Carole Chaski, who founded the Institute for Linguistic Evidence in Georgetown, Delaware, unless it is based on scientific methodology that is replicable from case to case.

Unless linguists produce verifiable data, says David A. Harris, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law and a former Maryland public defender, it’s just a matter of time “until they get the wrong person and are proved wrong by DNA.”

“Experience shows that is what happens.”

—

Stacey Castor, now doing time in Bedford Hills, New York, for murdering her husband in 2005 and attempting to murder her daughter two years later, helped give herself away, according to Fitzgerald, by misspelling — and mispronouncing — “antifreeze” as “antifree.”

One of many missteps that landed Albert Perez on Pennsylvania’s death row for murder six years ago was his punctuation, Fitzgerald says. Specifically, his misuse of ellipses.

And the 83-word note supposedly written by prolific diarist Jocelyn Earnest to explain why she had taken her own life didn’t strike Fitzgerald as long or “flowery” enough to be her work. Fitzgerald says his testimony that it was a forgery was key to a 2010 homicide trial in rural Virginia. Earnest’s estranged husband, Wesley Earnest, was later convicted of murder.

In these cases, Fitzgerald found traits in apparent suicide notes that suggested to him that the people who had died had not written the notes; they had been killed. He calls texts like these “Q documents” because their authorship is questioned. He compares the Q documents with “K documents” (their authorship is known) from the victim and potential suspects, looking for common features that he believes indicate common authorship.

The “intuitive” nature of the process is evident from Fitzgerald’s reports. Carefully observed factors such as “design, composition and style” suggest to him that Jocelyn Earnest’s known writing is “not-consistent” with the suicide note. In the Castor case, Fitzgerald attributes some anomalies to the author’s attempt to disguise herself by “dumbing down” her writing but suggests that repeated uses of “antifree” are not dumbing down but the author’s “actual lexical usage.”

Fitzgerald adds a “quantitative element” to this “qualitative analysis” by comparing the stylistic nuances he finds with a database to provide “basic statistics” on how rare a usage is. Internet searches, the Dictionary of American Regional English and consultation with linguists convinced Fitzgerald that Stokes’s use of “light bug,” for example, was “a personalized dialectal feature used by this one person.”

Fitzgerald, 61, won’t talk about current cases, but he’s happy to demonstrate how he examines a text. He pores over a typed document in his office at Academy Group Inc., the forensic behavioral science company in strip-mall Manassas where he now works, leaning forward as he scans the pages.

His finger suddenly stops. Here’s a misspelled word (“recieve”). An omitted adverbial ending (“unexpected(ly) fall”). And a mismatched tense (“hasn’t open(ed) your eyes”).

“I’m not comprehending,” Fitzgerald says, explaining that he doesn’t want the words’ meanings to throw him off the lexical scent. “I’m looking for clues.”

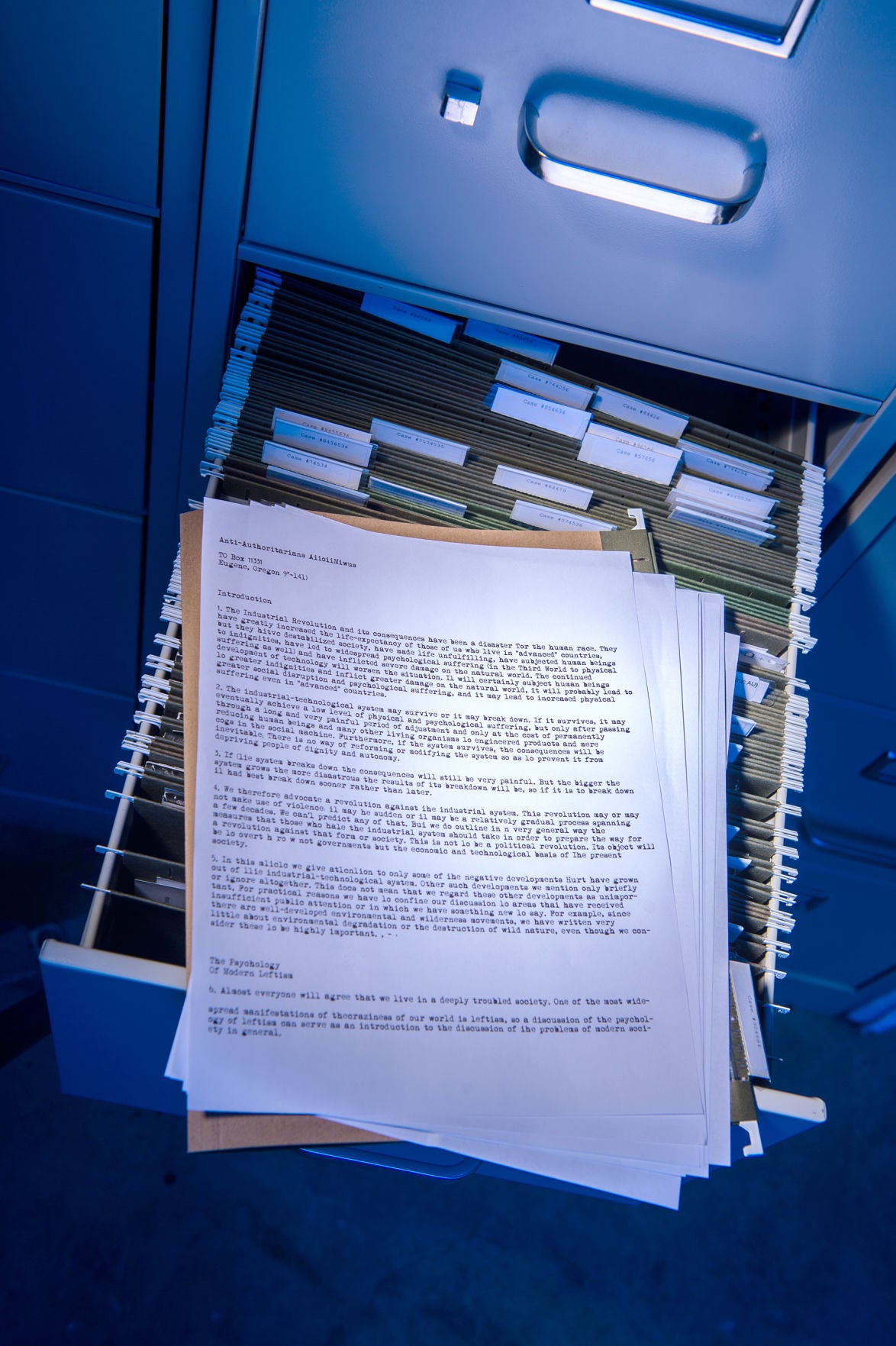

The “evidentiary value” of language became clear to him in the mid-’90s, the affable former Philadelphia cop says, shortly after he joined the FBI’s behavioral analysis unit, when the bureau was on the hunt for the Unabomber. Once David Kaczynski drew attention to similarities between the published manifesto and his brother Ted’s idioms, Fitzgerald says he did a “comparative analysis” of the manifesto and examples of Ted Kaczynski’s writing, turning up quirky usages. (“You can’t eat your cake and have it too.”) That persuaded a judge to authorize a search of Ted Kaczynski’s mountain cabin, which revealed a stash of bomb-making equipment.

Fitzgerald says the case led him to help “transition the field into law enforcement as a proactive tool to solve crimes.” It also introduced him to the band of linguists who were transferring their academic skills to the more practical — and profitable — world of the law.

Among them was Roger Shuy, the now-retired Georgetown professor often regarded as the founder of forensic linguistics, who once helped identify a kidnapper by alerting police that the term “devil strip” — found in the ransom note to describe the patch of grass between a sidewalk and a street — is used almost exclusively by people from Akron, Ohio.

Another figure is Robert A. Leonard, former lead singer of the rock group Sha Na Na, who helped start the country’s only master’s program in forensic linguistics at Hofstra University in 2010 and recruited Fitzgerald as an adjunct.

Fitzgerald got a master’s in linguistics from Georgetown in 2005, retired from the FBI in 2007 and joined AGI. His academic adviser, Natalie Schilling, became an associate at AGI, and he became a guest lecturer in her course. Together they run workshops for law enforcement.

Fitzgerald keeps a tie behind the door of his office at AGI, where all eight partners are former behavioral analysts.

“You learn that in the FBI,” he says, to “have a tie ready in case … you have to go to court.” He has appeared as an expert witness 10 times; a measure of his method’s success, he says, is that many cases never make it that far because “problematic writings mysteriously stop” or suspects confess when presented with his analyses.

The process is like “behavioral analysis,” Fitzgerald says, “but with more science behind it.”

—

Just how much science is what bedevils not only linguistic analysis but also other forensic work. Unless you have statistical proof matching evidence to individuals, Solan says, “How do you know you are right?”

“The forensic sciences were born in the police crime lab, not the science lab,” explains Harris, the law professor, and “based largely on human interpretation and experience.” Even the venerable art of fingerprinting is “not really science in the true sense of the word,” he says.

Which is not to say fingerprinting — or linguistics — doesn’t produce valuable evidence.

“Fingerprinting is most often right,” Harris says. But to call it science “cloaks the work in a sort of aura of certainty.”

When DNA analysis came along in the ’80s, experts could suddenly state their accuracy based on population studies. And that is what every forensic discipline, including linguistics, needs: “basic foundational science that proves it’s valid,” Harris says.

His view is buttressed not only by DNA’s overturning of convictions that relied on ballistics, hair analysis and bite marks, but also by a series of steps over the past couple of decades: a 1993 Supreme Court case, Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, requiring more stringent scientific standards for expert testimony in federal courts, including known error rates; a 2009 report from the National Research Council urging comprehensive reform of forensic sciences; and two bills before Congress aimed at improving standards.

That’s the backdrop against which linguistics came to the attention of the legal system, introducing its own set of language-specific uncertainties: There is debate, for example, over whether we each have an “idiolect,” or unique linguistic fingerprint. And if we do, how consistent is it in academic essays or love letters as opposed to, say, emails and text messages? Betcha its not!! 🙂

Each piece of writing may reflect the interventions of an editor or an autocorrect program, as well as the author’s efforts to disguise his or her style.

And the amount of data matters: Identifying the writer of a single-sentence bank robbery note is trickier than verifying that I composed this 3,000-word article, with the many clues to my identity I’ve surely left here, even after editing out traces of my native British English for fear U.S. readers would think them misspelt.

Then there is the question Solan alludes to: whether computer scientists can come up with measurable methods that reflect an understanding of language, but without the judgment calls of the intuitive approach. Solan and others see advances in those techniques, as does Duquesne associate professor Patrick Juola, who used software to identify J.K. Rowling as the likely author of “The Cuckoo’s Calling.” Juola, who compared such factors as word length and groupings of adjacent characters in the novel with other likely suspects such as P.D. James’s “The Private Patient,” Val McDermid’s “The Wire in the Blood,” Ruth Rendell’s “The St. Zita Society” and an earlier Rowling work, believes computerized author ID may eventually prove as accurate as DNA analysis.

But, says Juola, who helps run an international competition to find the best methods, “We’re not there yet.” So far, to his disappointment, no human experts have taken on the computer scientists in the annual contest. Fitzgerald says “it is presently inconclusive as to which method may have the lowest error rate.”

For all the headline-making successes some analysts have claimed in the literary world, the data there are often extensive, and the stakes aren’t high.

Nobody ends up behind bars for being wrongly accused of writing “The Cuckoo’s Calling.”

The search for sounder science is what motivates Carole Chaski to explore methodology “grounded in linguistics.”

Chaski, 59, who runs a nonprofit and related business, considers herself something of an outlier in the field: She believes the key lies not in scanning texts — whether by eye or machine — for superficial idiosyncrasies, but in surfacing the syntactic structures linguists study. She has been blind-testing her methods for two decades and getting “robust” results, she says.

This is arcane stuff, which Chaski set out to explain at the opening of a four-day workshop last summer when she assembled about 10 experts — computer scientists, DNA and legal specialists among them — at her Salty Paw Farm on 17 rain-swept acres of the Delmarva Peninsula.

The gathering has the feel of a salon, with meals in the house among Chaski’s clutter of books and tea sets and where discussions range from computer programming and literacy projects to the double rainbow that arced over the previous evening’s sky. But walk out to the barn, where Chaski has created a conference room, and the atmosphere becomes as charged as the electrical storm that just passed through.

“Empirical research.” “Ground-truth data.” “Error rate.” These are the words echoing among the group.

Chaski, who taught linguistics at North Carolina State University in the early ’90s, organized a symposium at the Linguistic Society of America’s January meeting to help linguists learn how to serve the legal community. And part of what she is doing here is to educate her audience — just as she might educate a jury — about the scientific study of language and its structure.

“A linguist looks at language behavior, not what is right or wrong,” Chaski says.

She walks over to a white board, grabs a marker and writes two sentences.

He picked up the pill/He picked up the bill

Change the “p” sound to a “b” sound and you change not only the meaning of the noun but also the meaning of the preceding verb, she explains. In the second sentence, “picked up” can mean “paid.”

It’s an entertaining game, a Linguistics 101 illustration of how much information is embedded in a sentence that doesn’t show up in spelling. The group begins spotting other patterns. Reorder the words (He picked the pill up/He picked the bill up), and in the second sentence, “picked up” no longer means “paid.”

The atmosphere is feisty as focus returns to author identification, and Chaski seems to thrive on the verbal parrying. After a research fellowship at the Department of Justice, she founded the first nonprofit devoted to research in forensic linguistics in 1998. A partner for-profit company, ALIAS Technology, provides related software and services.

Chaski does not reveal exactly how her method works but says she has reached accuracy rates of about 95 percent from computational analysis of “constituent structures” — the usually subconscious ways people group phrases within a sentence. Some people, she explains, produce complex noun phrases and simple verb phrases; others produce complex adverbial phrases, and so on. By focusing not just on the parts of speech but on how those parts of speech are used, her analysis gets away from a dependence on words and spelling.

Why does she believe that is important? If you have a supposed suicide note, Chaski says, “the other documents you get from the suspect and from the victim might be love letters, essays, school assignments.”

“Doing it by words is not going to work at all,” she argues. “Most people write suicide notes only once.”

The need for measurable science becomes all the more compellingin the contemporary courtroom, where popular crime shows such as “CSI” and “Criminal Minds” are having “real-life-consequences,” according to the National Research Council report:

“Jurors have come to expect the presentation of forensic science in every case, and they expect it to be conclusive.”

If our language is indeed as distinctive as our DNA, we haven’t yet decoded it. That leaves a piece of punctuation looming over the life stories of people convicted based, at least in part, on clues found in their written words.

And it’s a large question mark.