Gun industry’s helping hand triggers a surge in college shooting clubs

Published 11:15 am Sunday, March 15, 2015

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. – In between completing problem sets, writing code, organizing hackathons, worrying about internships and building solar cars, a group of MIT students make their way to the athletic center, where they stand side-by-side, load their guns and fire away.

They are majoring in biological engineering, brain and cognitive sciences, aeronautics, mechanical engineering, computer science and nuclear science. Before arriving at MIT, nearly all of them had never touched a gun or even seen one that wasn’t on TV.

“Which is strange because I’m from Texas,” said Nick McCoy, wearing a T-shirt advertising his dorm and getting ready to shoot.

McCoy is one of the brainiacs on MIT’s pistol and rifle teams, which, like other college shooting teams, has benefited from the largesse of gun industry money and become so popular that they often turn students away. Teams are thriving at a diverse range of schools: Yale, Harvard, the University of Maryland, George Mason University, and even smaller schools such as Slippery Rock University in Pennsylvania and Connors State College in Oklahoma.

“We literally have way more students interested than we can handle,” said Steve Goldstein, one of MIT’s pistol coaches.

While some collegiate teams date to the late 1800s, coaches and team captains say there is a surge of new interest from students, both male and female, finally away from their parents and curious to handle one of the country’s most divisive symbols. Once they fire a gun, students say they find shooting relaxing – at MIT, students call it “very Zen” – and that it teaches focusing skills that help in class.

Some also find their perceptions about guns changing.

“I had a poor view, a more negative view of people who like guns than I do now,” said Hope Lutwak, a freshman on MIT’s pistol team. “I didn’t understand why people enjoyed it. I just thought it was very violent.”

And that’s precisely what the gun industry hoped it would hear after spending the last few years pouring millions of dollars into collegiate shooting, targeting young adults just as they try out new activities and personal identities.

The National Shooting Sports Foundation, a powerful firearms lobbying group, has awarded more than $1 million in grants since 2009 to start about 80 new programs. A couple who owns a large firearms accessories company founded the MidwayUSA Foundation, funding it with nearly $100 million to help youth and college programs, including MIT. The National Rifle Association organizes pistol and rifle tournaments, including the national championships next weekend in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Zach Snow, who oversees the college shooting program for the NSSF, said, “This is something the industry overlooked for a number of years.” And now that the industry is paying attention, the growth has been phenomenal. The upcoming collegiate clay target championships – George Mason has won 11 titles, including in 2013 – has swelled from a few hundred shooters in 2010 to more than 700 this year.

Though industry groups distribute booklets to students counseling them on how to start programs and deal with reluctant administrators or communities – tips: write letters to the editor in the school paper and sponsor bake sales – officials say the teams haven’t generated as much pushback as they expected. Shooting is even publicized as a recruiting and teaching tool.

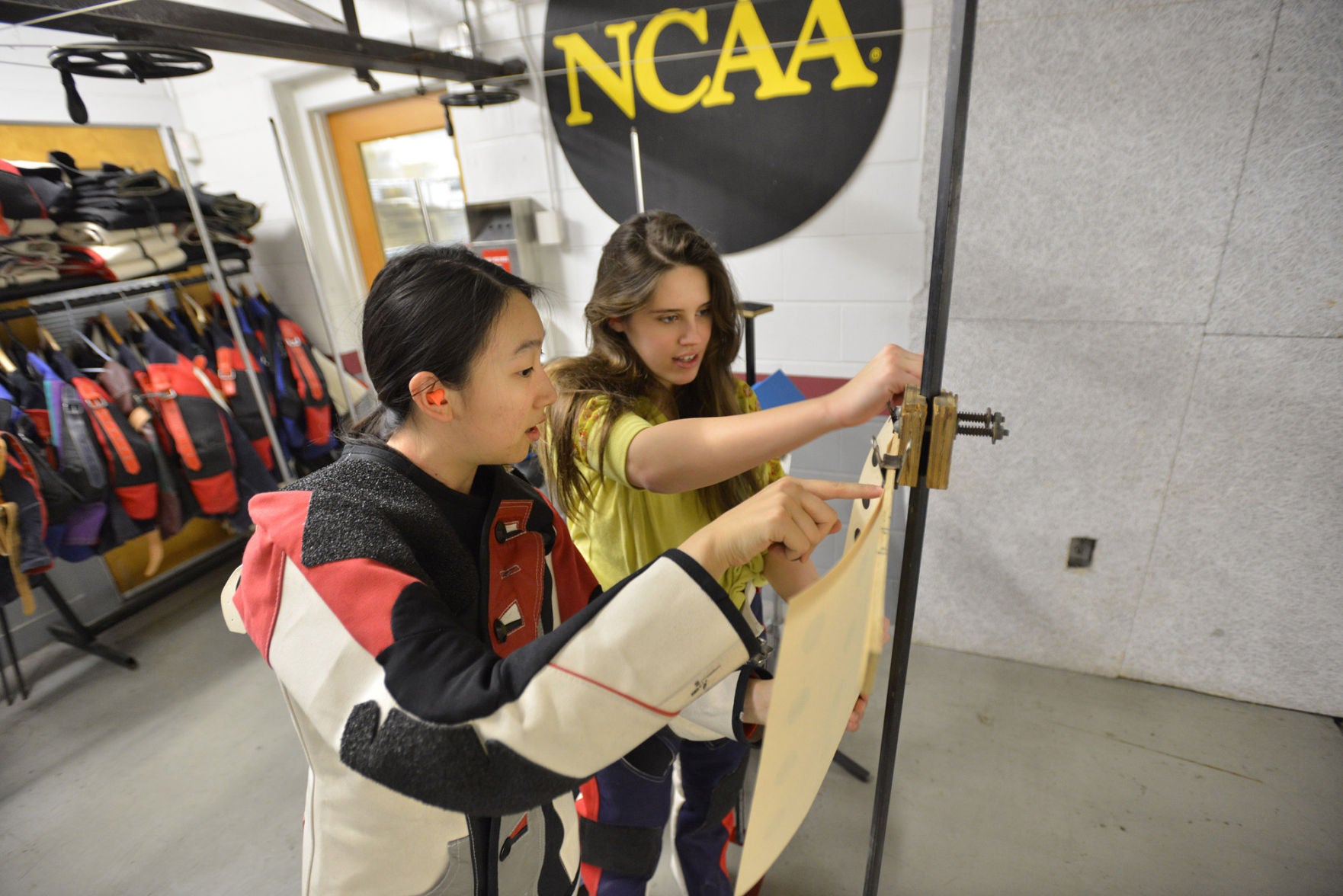

MIT offers a shooting class that fills up in mere minutes. A recent post on MIT’s admissions blog featured Lydia Andreyevna Krasilnikova, a mechanical engineering major, writing about a class rifle competition.

“We had five minutes for five rounds,” Krasilnikova wrote. “It was my first time aiming below the bull’s eye. At this point I was extremely nervous. My arms were shaking. I tried to time my breaths to pause when the jitters paused, fire when they coincided with my breath, and stop between rounds to pace myself. And I won!”

Shooting has taught her many metaphors to live by, including, “Focus on the shot you’re lining up now, not the one you just took, not the ones you’ll take in the future.”

– – –

MIT’s pistol and rifle teams practice about four times a week underneath a gym. The range seems Paleolithic compared with higher-end establishments with expensive electronic target retrieval systems. Students send and retrieve their targets on a metal wire by winding a hand crank. Shooting booths are separated by window screens.

Students use air guns and standard .22 caliber competition rifles and pistols. In a pinch, they have made tiny replacement parts for grips with a 3-D printer, giving them an advantage over less tech-savvy schools. The school and team captains are obsessed with safety, and the coaches make sure students handle their school-issued guns properly.

Pistol team members walk slowly to the firing line, pointing their unloaded guns straight up. They practice squeezing the trigger without any rounds loaded. Then they load up, set their stance as methodically as a baseball player getting comfortable in the batter’s box, and fire away. Goldstein, a former MIT student shooter, periodically offers kernels of wisdom during breaks from firing.

“You want to be calm,” he told a student the other day, “but you don’t want to be passive.”

Most of the MIT students say shooting is the one tranquil moment in long days filled with complicated problem sets, lab meetings and lectures, not to mention pressure from their parents.

“It’s a way to block out all the horrors of MIT and every other thing stressing you out,” said Abra Shen, a junior on the rifle team, which is coached by Melissa Mulloy-Mecozzi, a former U.S. Olympian shooter. “It’s taking a break from the mental chaos and calming down.”

For some students, particularly those who grew up shooting things on their TV screens, it’s not what they expected.

“I thought it would be more active, moving around and stuff, like a SWAT team,” said Kevin Ng, a sophomore rifle team member who is also in the Chinese Lion Dance club. “I said, ‘Oh, I guess it’s not, but let’s give it a shot and let’s see how I do.’ I liked it.”

The teams compete in about a dozen matches and tournaments a year against other schools, including Army. Students treat competitions as seriously as a final exam, if not more so.

Afraid of his firing hand shaking, Thuan Doan, the pistol team’s captain, does not drink caffeine during the season. (He sometimes cheats on Fridays, when there is no practice. Shhh.) Team members even adjust their sleep schedules depending on match start times. For the upcoming national tournament, Doan said, “We have to get up at eight, which is just obscene.”

– – –

MIT’s rifle team is a varsity sport, competing in NCAA-managed matches with funding from the athletic department. The pistol team is a club sport, meaning it must get its funding elsewhere. For that, it relies heavily on the MidwayUSA Foundation, which sets up an account for each school that alumni or others donate to. The foundation then matches donations and invests the money. Teams can draw 5 percent of their funds each year. The pistol team’s account balance is more than $363,000.

Dick Leeper, the foundation’s director, insists the couple behind the charity, Larry and Brenda Potterfield, didn’t start the foundation because they wanted more customers for their business.

“They wanted people to experience what they’ve experienced all their lives,” he said. Asked why shooting had taken off in recent years on campuses, Leeper said, “You can go look up the club sports and do soccer, badminton, bingo whatever – this is something that’s a lot more exciting.”

At MIT, students who successfully pass classes in shooting, sailing, archery and fencing are given a ceremonial pirate’s certificate.

Some students plan to continue shooting after graduating, but others say it will depend on family situations and how tough regulations are wherever they wind up.

And they acknowledge that many in society don’t think about firearms the way they now do – that it’s less about the gun, as one student put it, and more about who is using it.

Sometimes their friends ask, “Are you like a gun nut now or something?”

Doan, MIT’s pistol team captain, has been on the team four years – without telling his parents back home in California.

“I know they’d freak out about the safety aspect,” he said. “They are very cautious, and I don’t want them to worry.”

But other parents have come around.

At first, Ng’s parents asked: “Are you going to get shot? Is some crazy guy gonna shoot you? Are you going to get in trouble with the state for shooting guns?”

Now, he said, “It’s just really casual. They just want to know if I’m still doing my schoolwork.”