Which group of adults did the Chicago Little Leaguers wrong?

Published 11:46 am Thursday, April 2, 2015

CHICAGO — Some saw the news on their televisions as they dressed for school or caught fleeting references as they stole pre-dawn glances at Twitter. Others were still in bed, just waking up, when a parent broke the news. Still others, such as outfielder/pitcher Lawrence Quincy Noble, were already on their way to school when a call came in.

“It’s your grandmother, Q,” Noble’s grandfather told him from behind the wheel, using his grandson’s nickname. “They’re taking the title away from you.”

In the immediate aftermath that morning, Feb. 11, there were tears shed all over the south side of Chicago. “It took away a little piece of my heart from me,” recalled Noble, 13, who tried to muddle through the school day but required early dismissal at 11:30 a.m. after he buried his face in his hands at his desk and started crying.

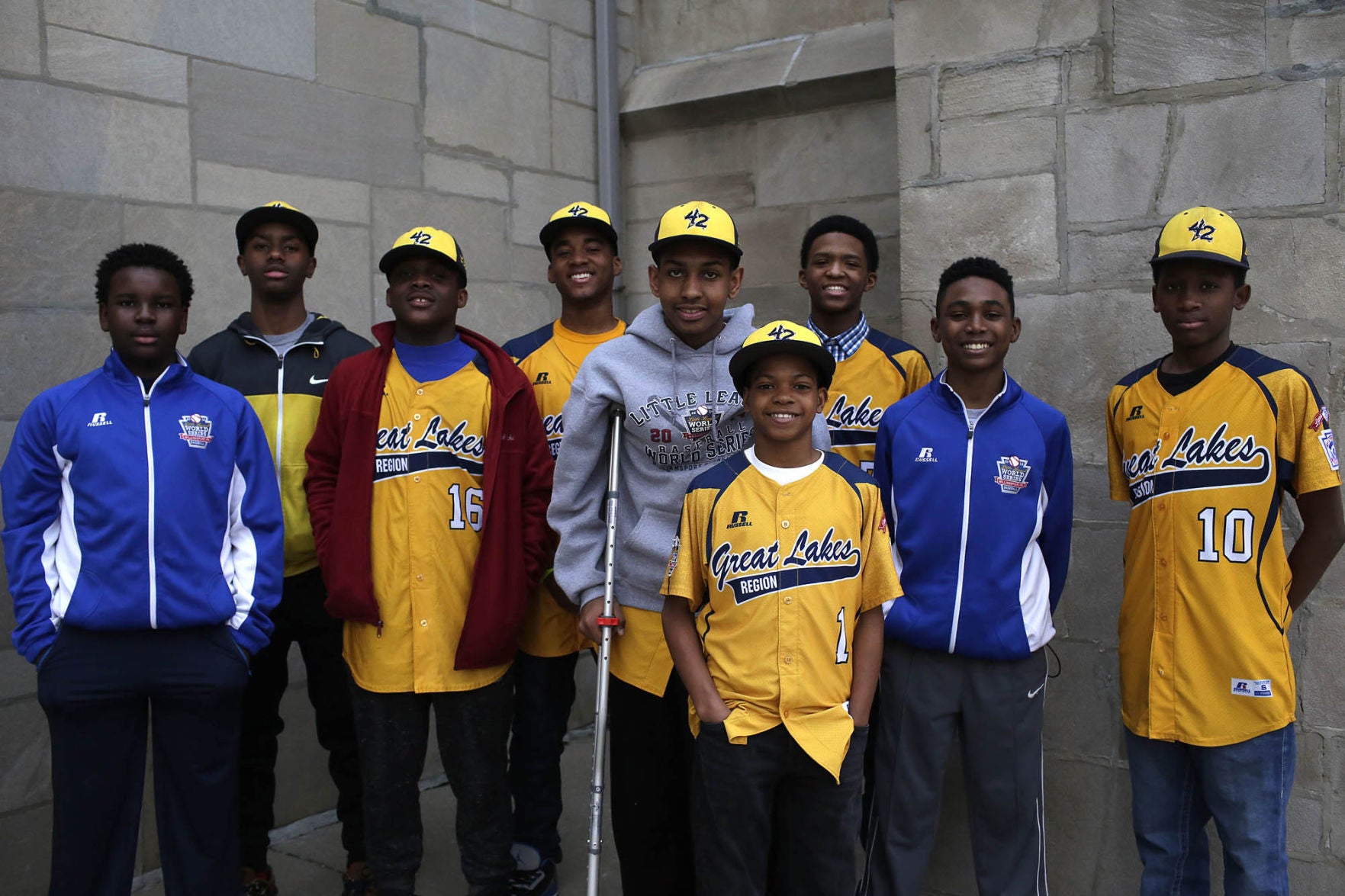

There was also anger and confusion, as well as a dark, gnawing feeling that someday, looking back, they might recognize as the ending of their childhoods. For the 13 members of the 2014 Jackie Robinson West Little League team, the news that Little League Baseball had stripped them of the U.S. championship they had won in the Little League World Series last August was a trauma they are still struggling to get over.

“I could never get over it,” second baseman Marquis Jackson said.

These days, the players can see the circle of grown-ups around them expanding beyond their parents and coaches, to include lawyers, public relations consultants and — soon — psychological counselors. All of it speaks to the complex legal and PR machinations going on around them, as well as the hurt that hasn’t gone away.

The parents, coaches and PR consultants agreed this week to let the boys give The Washington Post their first extensive interviews about what has happened to them over the past seven months. Subsequently, Little League Baseball agreed to provide its first full, public accounting of its decision to strip Jackie Robinson West’s title.

Expand the players’ circle out even further, and it would include, on one side, their countless fans and supporters who have expressed encouragement and signed petitions asking Little League officials to give the boys their title back; and, on the other side, the critics, mostly cloaked in social-media anonymity, who call them “cheaters,” sometimes dropping in a racial epithet for good measure.

What is clear is that some grown-ups have done wrong by these boys, who captivated the nation last summer by becoming only the fourth all-African-American team to win the U.S. title, only to have to it stripped when Little League determined team administrators had “falsified documents,” according to Little League officials, in order to make eligible a half-dozen players who otherwise were not within Jackie Robinson West’s territory.

The question that continues to divide people inside and outside the team’s circle is this: Which group of grown-ups did them wrong?

– – –

By the start of each Little League “tournament season” — roughly mid-June for the Great Lakes region, when all-star teams are chosen to compete at the district, section, state and regional levels, with bids to the World Series awaiting the regional champion — each league is required to submit a map of its territory, plotting the residences of each player.

According to Little League officials, the map for Jackie Robinson West — a storied league on Chicago’s south side that had made it to the Little League World Series in 1983 and fell a game short in 2013 — was signed off, per Little League regulations, by team manager Darold Butler and league president Anne Haley. Also signing off was Michael Kelley, the administrator of Illinois Little League District 4, which comprised Jackie Robinson West and five other Chicago-area leagues. Standard documentation was also required, showing proof of residency for each of the players.

The boys from the team, all of them 11 or 12 years old, blitzed through the tournament season, culminating in a victory in the Great Lakes Region championship game over New Albany, Indiana, to earn them a berth in the World Series, followed by a thrilling 7-5 win over Las Vegas to secure the national title in South Williamsport, Pennsylvania. No questions were raised over the eligibility of any of the players, at least not publicly.

But after the World Series, an administrator from a rival, suburban league went to Little League with allegations that the team had used players from outside its territory, which would have made them ineligible. Eligibility questions are common for Little League, with roughly 50 to 75 protests occurring each year across its many baseball and softball divisions, the vast majority of them resolved at the district level.

In September — a month after Jackie Robinson’s run had ended in a loss to South Korea in the world championship game — Jackie Robinson and Illinois District 4 officials were asked to submit a new, more detailed map of the league’s territory, this one containing street names. This map was dated May 1, 2014, according to Little League officials. But the players’ residences all checked out, and all were within the marked territory, so Little League, satisfied all the players were eligible, considered the matter closed.

By December, however, Little League officials received a call from a reporter with the local-news website DNAinfo saying an official from another league within District 4 was claiming Jackie Robinson West’s map had annexed without permission territory from three adjoining leagues — presumably for the purposes of making players from outside its own territory eligible.

Little League investigated again, and found the original map and the newly submitted map contained different boundaries and different plots for some players’ residences. But Kelley, the District 4 administrator, said the maps for the district’s six leagues had been redrawn before the season, and explained that an old map had been mistakenly submitted with Jackie Robinson’s original documentation. Little League again considered the matter closed.

Then, at a Jan. 31 meeting in Chicago, officials from the three rival leagues told Little League officials that Kelley and Jackie Robinson treasurer Bill Haley had asked those three leagues to sign off on the newly drawn map — well after the fact. Presented with this information, Little League officials confronted Haley, who, they said, acknowledged making that request. Haley, they said, also acknowledged that Jackie Robinson had backdated to May the second, more detailed map to make it appear it had been approved before the season, when in fact it was drawn — without the permission of the adjoining leagues — in September.

“They obviously knew they had taken territory that didn’t belong to the league, so they made an attempt to meet with the other leagues and essentially ask, ‘Will you give us this territory?’, and [the other leagues] said no,” Little League president and CEO Stephen Keener said in a telephone interview Wednesday.

Haley, whose father founded Jackie Robinson West in 1971, declined to comment, but through a spokesman he denied Little League’s contention that he acknowledged the backdating of the second map and the requesting of the other leagues that they approve the new boundaries after the fact.

Butler, whose son, D.J., was a center fielder for Jackie Robinson West, declined to comment. Kelley, a Chicago firefighter, could not be reached.

A lawyer working on behalf of Jackie Robinson West, Victor Henderson, said in a telephone interview he is considering legal action against Little League, but he did not dispute outright the league’s contentions.

“The story is more nuanced than has been painted so far,” Henderson said. “It’s not a black-or-white issue. An analogy [would be] if someone does 56 in a 55-mph zone, I can’t tell you someone may not have been over speed limit, but there is also the issue of the penalty. So I cannot tell you there may not have been some things that [Jackie Robinson West] should have done differently.”

On the afternoon of Feb. 10, Little League officials met and arrived at a difficult decision: It would vacate the team’s wins, handing the Great Lakes regional title to New Albany and the U.S. title to Las Vegas, and would remove Butler, Anne Haley, Bill Haley and Kelley from their positions. (Anne Haley is Bill Haley’s mother.) Later, Little League dissolved Illinois District 4, shifting its six leagues, including Jackie Robinson West, to a pair of nearby districts.

“It was a difficult situation for everybody,” Keener said. “The teams along the way who were denied the opportunity to advance through the tournament, those kids lost something, too. While we understand [Jackie Robinson’s] heartbreak and their being upset about it, we have to do our very best to maintain the fairness of our program. Clearly, violations occurred. Adults are responsible for it, and unfortunately it’s the kids who had the championship taken away. But all the other kids along the way we feel bad for as well.”

Keener said he planned to call Jackie Robinson officials first thing on the morning of Feb. 11 and deliver the decision, then release a statement to the media at 10:30 a.m., Eastern time. As a courtesy to its television broadcast partner, Little League gave ESPN advance notice of the action, with the caveat that the information was embargoed until 10:30.

– – –

Right fielder Prentiss Luster heard the news on the car stereo on the way to school and started to cry. Third baseman Joshua Houston found out when his mom came in his bedroom and told him. The Butlers, Darold and center fielder D.J., realized there were news trucks outside their house when they saw the front of the house on their TV screen.

“I was real devastated,” first baseman Trey Hondras said.

Many of the players were kept out of school that day by their parents. Others, like Noble, tried and failed to make it through. In the weeks since, the pain may not be as constant, but it is still there and it is still acute.

“Sometimes there are nights where I just think about it,” Noble said.

Much of Jackie Robinson’s beef against Little League has to do with the way the players and their families found out about the decision. It turns out ESPN, according to Keener, defied Little League’s embargo and broke the news at around 7:45 a.m. EDT, or 6:45 a.m. Chicago time — before Keener had a chance to call team officials personally.

“We regret that happened the way it did,” Keener said. “But we took every precaution to do this the right way.”

ESPN acknowledged its mistake in breaking the embargo, saying in a statement, “It was an unfortunate error, which we regret.”

Henderson, Jackie Robinson’s lawyer, said the ESPN debacle was emblematic of the larger issue of Little League’s non-responsiveness to the team’s concerns. “There are people I’d like to speak to on the Little League side, and I haven’t gotten access to those people,” Henderson said. “And I think it might be unlikely I get access to them.”

Little League has also retained a lawyer to handle the matter, Keener said. Little League’s process for handling eligibility disputes includes an appeal option, which would be heard by its Charter and Tournament Committee, but Henderson said he is not interested in appealing.

“Absolutely not,” he said. “If I don’t have the relevant information, [it’s like] going up there with my pants around my ankles. I need all the relevant info. That’s window dressing. I would not advise my clients to do that.”

To the charge of withholding information, Keener said, “Not true. [Henderson] has written to us on several occasions to request info, and we have responded every time. All the documents that were used [in the decision] were [already] in possession of Jackie Robinson West.”

In the middle of it all, caught between the adults at Little League and the adults at Jackie Robinson West, between right and wrong, between puberty and their teens, are the 13 kids of Jackie Robinson West — trying to keep up the good fight, but also trying to move past the trauma of Feb. 11.

“Eventually I will have to [get over it], to move on and become better person,” Lawrence Noble said. “In my heart, I’ll know I’m still the U.S. champion.”