Sedation device could replace doctors

Published 7:17 am Tuesday, May 12, 2015

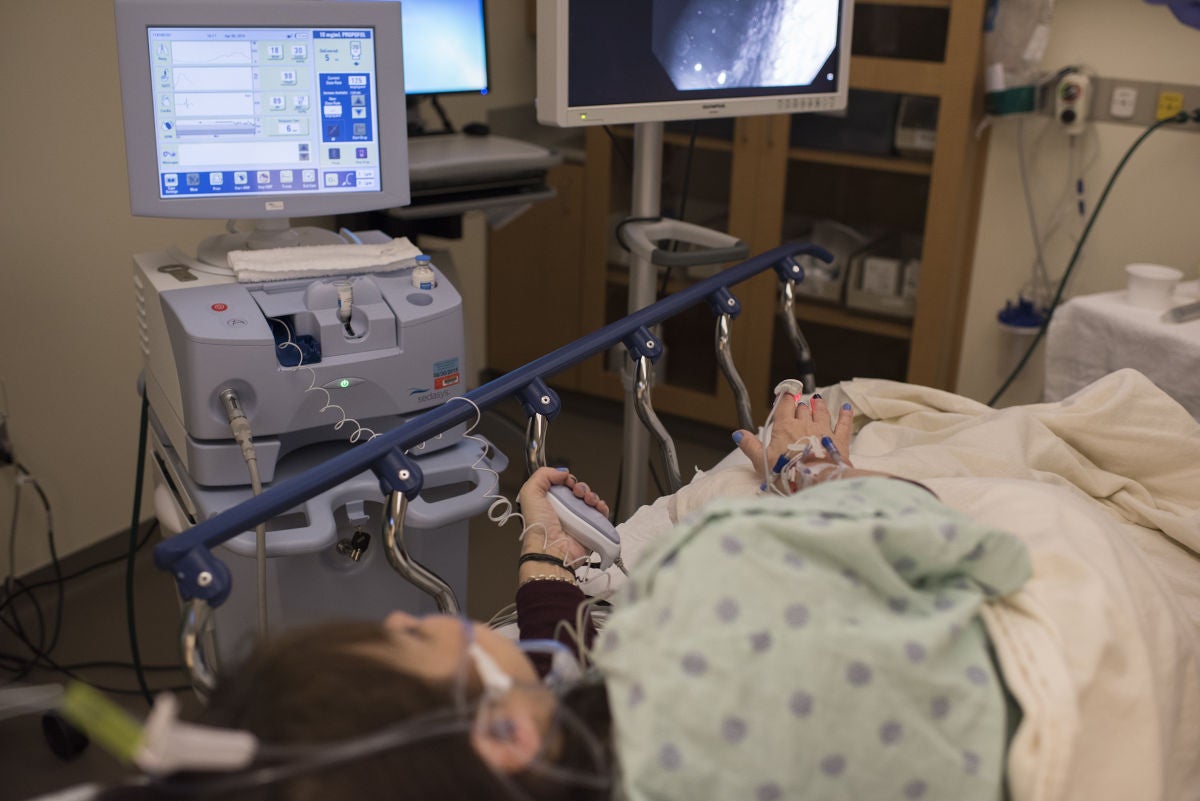

TOLEDO, Ohio — The new machine that could one day replace anesthesiologists sat quietly next to a hospital gurney occupied by Nancy Youssef-Ringle. She was nervous. In a few minutes, a machine — not a doctor — would sedate the 59-year-old for a colon cancer screening called a colonoscopy.

But she had done her research. She had even asked a family friend, an anesthesiologist, what he thought of the device. He was blunt: “That’s going to replace me.”

One day, maybe. For now, the Sedasys anesthesiology machine is just getting started, the leading lip of an automation wave that could transform hospitals just as technology changed automobile factories. But this machine doesn’t seek to replace only hospital shift workers. It’s targeting one of the best-paid medical specialties, making it all the more intriguing — or alarming, depending on your point of view.

Today, just four U.S. hospitals are using the machines, including here at ProMedica Toledo Hospital. Device maker Johnson & Johnson only recently deployed the first-of-its-kind machine despite winning U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in 2013. The rollout has been deliberately cautious for a device that hints at the future of health care, when machines take on tasks once assumed beyond their reach.

Everyone is watching to see how this goes.

“We’ve had a lot of anesthesiologists who’ve been dropping by to get a look,” said Michael Basista, the gastroenterologist who was about to work on Youssef-Ringle.

Then Sedasys did its job. And his patient was out cold.

Anesthesiologists tried to stop Sedasys.

They lobbied against it for years, arguing no machine could possibly replicate their skills or handle an emergency if something went wrong. Putting someone to sleep is an art, they said. Too little sedation, and the patient feels pain. Too much, and the patient dies. Anesthesiology requires four years of training after medical school, meaning careers might not launch until the doctors are in their 30s. It’s one reason the profession’s median salary is $277,000 a year, according to research firm Payscale.

At first, the FDA rejected Sedasys over safety concerns. That was in 2010. But Johnson & Johnson, which began work on the device in 2000, won approval by agreeing to have an anesthesiology doctor or nurse on-call in case of emergencies and to limit use to simple screenings such as colonoscopies and endoscopies in healthy patients.

“The indication is very narrow, which is comforting to anesthesiologists,” Paul Bruggeman, Sedasys general manager for Johnson & Johnson, said in an interview.

But that comfort might be short-lived. More advanced machines are in the works. Researchers at the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, are testing a device that can fully automate anesthesia for complicated brain and heart surgeries, even in children. Hospital administrators imagine the day when Sedasys or another device is used throughout their facilities for sedation.

“I dream about using it in bigger areas than endoscopy units,” said Joseph Sferra, vice president of surgical services at ProMedica Toledo Hospital, who had to overcome staff objections to get Sedasys into his medical center. “I’m sure this is very disconcerting to anesthesiologists.”

It is. But many have changed tactics. The American College of Anesthesiologists dropped its steadfast opposition as it became apparent Sedasys was going to get approved. The group instead pushed for restrictive guidelines.

Jeffrey Apfelbaum at the University of Chicago, co-chair of the professional group’s Sedasys committee, said he has doubts “about how it will pan out.”

“But is this a threat to a specialty?” he said. “Boy, I just don’t see it.”

Rebecca Twersky at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, the other committee co-chair, agreed.

“Clearly this is an example of disruptive innovation,” Twersky said.

“But,” she added, “we’re not going away.”

Even boxed into its corner, Sedasys could have a major impact.

Colonoscopies are among the most common medical procedures, with about 14 million done annually. The screenings are often uncomfortable and sometimes painful. Many patients would prefer to be knocked out, and in recent years anesthesia has grown more common for these procedures. In 2009, an estimated $1.1 billion was spent on traditional anesthesia services for colonoscopies, according to one research study.

Sedation can cost even more than the colonoscopy, with anesthesiology fees adding up to $2,000. By contrast, Sedasys costs $150 to $200 each time.

“There doesn’t need to be an anesthesiologist participating anymore,” said Bruggeman, the Sedasys executive.

In the Toledo hospital room, Basista told a nurse to begin. She pushed a button on the Sedasys machine, sending a measured dose of a sedation drug flowing into Youssef-Ringle.

The machine monitored her breathing, the oxygen levels in her blood and her heart rate. Youssef-Ringle also wore an earpiece, where a computerized voice periodically instructed her to squeeze a controller in her hand. The goal was to keep her in a period of moderate sedation — unaware but still responsive.

The machine was programmed with conservative parameters. If it detected even the mildest problem, it slowed or cut off the drug’s infusion. And that meant Basista and his two nurses had to constantly keep on top of patients.

“Hey, Nancy, take a deep breath!” a nurse said, when Youssef-Ringle’s blood oxygen was too low for the computer’s liking.

Nancy, in her sleepy state, did. The machine relented. Minutes later, the machine beeped again. Low blood oxygen.

“Hey, Nancy, deep breath! Deep breath!”

The machine allowed less leeway in the patient’s vital signs than any human anesthesiologist probably would have. Youssef-Ringle’s numbers were fine.

As the machine did its job, Basista did his job, threading a cabled camera through his patient’s colon and taking pictures.

Before Sedasys, Basista had two options for sedating patients.

He could turn to an anesthesiologist, but finding one at his short-staffed hospital was difficult.

He usually sedated patients himself with a drug such as midazolam. But the drug doesn’t work as well as stronger ones that are restricted to anesthesiologists. And midazolam wore off slowly. Patients would be in a day-long haze. They would linger in the hospital’s recovery area. Basista said it was a waste of time to give screening results or care instructions to patients in the recovery area. They never remembered the conversation.

Sedasys uses propofol, a powerful drug that works almost like flipping an on-off switch in patients. No hangover. Propofol’s quick action is ideal for colonoscopies, which usually take 20 to 30 minutes to complete. The drug’s reputation took a hit in 2009 after singer Michael Jackson overdosed on the drug at home and died. But when used properly, the drug is widely preferred by doctors as a sedative.

The difference is apparent in the hospital’s nine-bed recovery unit, which used to be filled with drowsy patients after a colonoscopy clinic. Most beds are empty now. Colonoscopy patients are ready to leave in 15 minutes.

“It’s amazing,” said Catherine Hall, a patient-care supervisor. “And it’s not like we’re rushing them out.”

The hospital is considering eliminating a nurse shift in the recovery room, said Sferra, the hospital administrator. And he thinks the machine’s speed — patients go to sleep and wake up more quickly — will allow the hospital to squeeze in more procedures. The hospital could add two to three more to the current 15 per day per colonoscopy suite.

Sferra and Basista said the Sedasys machine was better for patients, too. Clinical studies of Sedasys have shown patients like propofol-based sedation. At ProMedica Toledo, that’s important for competing with area hospitals for colonoscopy patients.

“Once I was asleep, I was out. But now I feel fine,” said Lisa McLaughlin, 49, sitting in the recovery area minutes after finishing her colonoscopy.

Before the procedure, McLaughlin worried the machine would not sedate her well enough.

“I guess this is the future,” she said, adding: “I hate to put anesthesiologists out of work.”

Later that day, Youssef-Ringle sat in recovery. She was alert. She wanted to know how long she was under.

Ten minutes, Basista said.

That felt like one minute, Youssef-Ringle said.

His patient was clear-minded enough that Basista didn’t worry she would forget when he told her the screening was clear. No problems.

Youssef-Ringle called her experience “amazing.” She had gone into this with reservations. The machine seemed like just another way to cut costs, to remove the human factor. But now, after the procedure, she said she saw a potential upside, too: There was no human error, either.