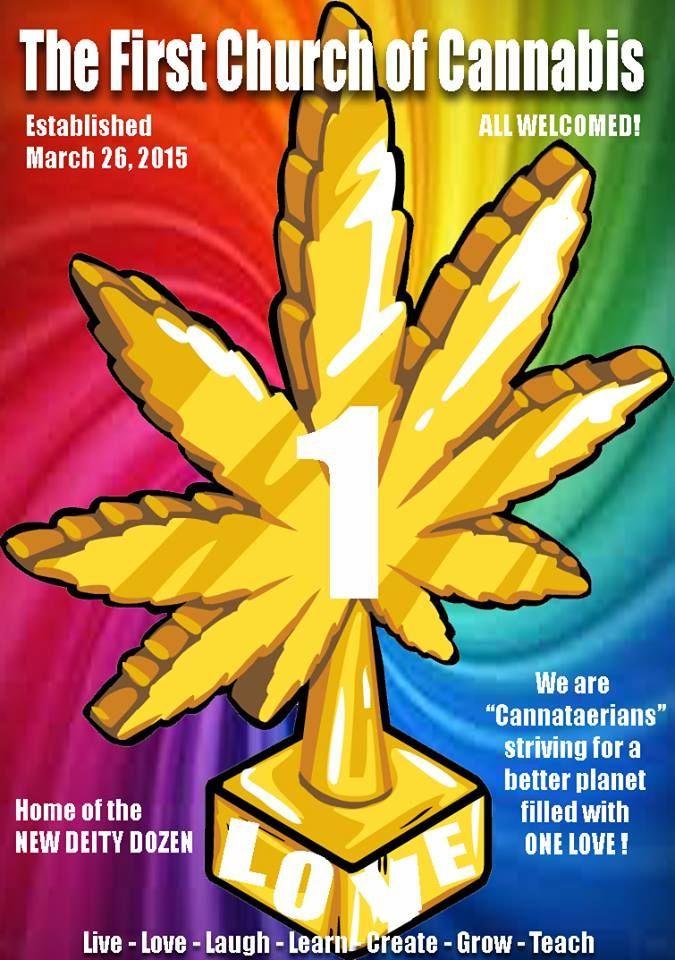

‘Pot’ church wins tax-exempt status

Published 7:59 pm Tuesday, May 26, 2015

INDIANAPOLIS – Peace, love, pot and a tax deduction.

It’s not exactly the Holy Trinity but it’s what the First Church of Cannabis hopes to offer supporters now that it’s incorporated as a tax-exempt religious organization.

Bill Levin, who founded the church to test Indiana’s new religious freedom law, was notified earlier this week that the Internal Revenue Service has granted his request for a status that allows donors to deduct contributions on their taxes. IRS documents provided by Levin confirm the agency’s approval.

“It means people in higher tax brackets will be more generous with the church,” said Levin, a longtime marijuana legalization advocate in Indianapolis. “There have been people who want us to succeed but they’ve been waiting us to get our 501(c)3 exemption.”

Levin’s new church may need the money: It’s still looking for a place to lease so it can hold its first church service on July 1, when Levin promises that worshippers “will light up” and fill the sanctuary with marijuana smoke.

Levin organized the church in March and recruited board members shortly after the state General Assembly passed the divisive Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which is also set to go into effect July 1.

The Secretary of State has already officially recognized the church as a religious, non-profit corporation, according to state officials, with the stated intent “to start a church based on love and understanding with compassion for all.”

But a court fight may also be looming. Tenets of the church include consuming cannabis on a daily basis as a sacrament.

Marijuana is currently illegal in Indiana for both recreational and medical use. Levin started the church to test the application of the new law that bans government from interfering with the exercise of religion.

The law prevents government from placing excessive limits on a person’s religious practice absent a compelling governmental interest. It is patterned from a 1993 federal law that aimed to protect traditional Native American ceremonies involving peyote.

But the Indiana law – and a wave of similar proposals elsewhere – sparked national debate about its intent, with opponents arguing that it’s a guise to discriminate against gays and lesbians by condoning a business’s refusal to serve same-sex couples.

Levin, who is not an ordained minister but calls himself the church’s “Grand Poobah,” is convinced his church fits the bill. He argues the state has no compelling interest in preventing church members from smoking pot.

And he doubts local police will bust a church service.

“I don’t think they’re going to come into the church and arrest us,” Levin said. “They don’t go into a church now and stop people under 21 from drinking sacramental wine that’s part of a service.”

State Attorney General Greg Zoeller has yet to weigh in publicly on the issue. A spokesman for Zoeller said he’s not been asked yet to advise law enforcement on how to respond to Levin’s promise to light up during church services.

Marion County Prosecutor Terry Curry has also declined to say what action he would take. Curry opposed the religious freedom law and warned that it would be used as a defense by drug offenders who claim that they are exercising their “religious right” to smoke pot.

Earlier this month, a northern Indiana judge rejected a similar argument by a man who claimed he grew and consumed marijuana as a follower of the Rastafari faith, whose members believe cannabis is a holy herb.

Indiana University McKinney School of Law professor Robert Katz, a First Amendment expert who’s studied the new religious freedom law, said Levin and his fellow church-goers will have also hard time making their case that pot-smoking is a sacred rite since the church appears that it was formed for the purpose of skirting drug laws.

“I think most judges would view them as goofballs,” Katz said. “The bottom line is they can’t make a credible case. It doesn’t even pass the laugh test — or maybe it does since they seem to be getting a lot of attention.”

The organization’s tax-exempt status and recognition as a religious organization by both the state and federal government won’t help its argument that marijuana-smoking is a sacred ritual.

Katz said the threshold for tax-exempt status as a church is low, and the IRS gives little scrutiny of an organization on the front end.

Indiana law makes it “extraordinarily easy” to be recognized as a non-profit religious organization, he said. “You don’t know even need to state the purpose of your organization on the (request) form. Under Indiana law, it’s optional.”

Still, Levin said he plans on forging ahead if he can find a place to hold the worship service.

“I’m not going to let fear of what might happen stop me,” he said.

Levin says the church won’t be buying or selling marijuana. But it does plan on petitioning the state seed commissioner for a permit to grow hemp – a strain of cannabis that lacks the levels of the psychoactive chemical that gives marijuana smokers their high. Federal law gave some states, including Indiana, authority to grow hemp for research. Only Purdue University now has permission to do so.

Indiana Seed Commissioner Robert Waltz says no one from the First Church of Cannabis has contacted him. But he doubts it would qualify.

“The federal law says it’s for research institutions only,” he said.

Maureen Hayden covers the Statehouse for CNHI’s Indiana newspapers. Contact her at mhayden@cnhi.com