U.S. sailor survived 2 sinking ships during World War II

Published 6:16 pm Tuesday, November 13, 2018

- Johnny G. Womack Sr., just after he enlisted in the U.S. Navy at age 19.

By Beth Alston

AMERICUS — Johnny G. Womack Sr. of Americus was 19 years old when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy on June 7, 1942, only been two weeks after he had graduated Americus High School.

While most veterans have stories to tell about their war experiences, Womack Sr. died in 1984, but his son Johnny Womack Jr. has a box of his father’s wartime memorabilia, newspaper clippings, letters, photos, and etc., which he shared with the Americus Times-Recorder recently. Womack Sr. served his country well, surviving the sinking of two ships on which he was serving.

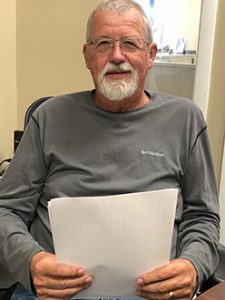

Johnny G. Womack Jr., who shared his late father’s wartime stories with the Americus Times-Recorder.

Early on, Womack was an apprentice seaman on the Stanbac Wellington, a tanker ship, serving on a gun crew for nine months until the ship was struck by three German torpedoes. Womack was one of only three or four survivors from a crew of 80. The survivors remained on two lifeboats and a raft for more than three and half days being rescued.

After returning from that harrowing experience, Womack, a gunner’s mate, was assigned duty on the tanker Gulf Belle, loaded with aviation fuel, which left port on the Eastern seaboard headed for the Pacific via the Panama Canal. At least that was the plan.

On Oct. 24, 1943, off the coast of Florida, something horrendous occurred. Another tanker loaded with gasoline, the Gulf Land, and the Gulf Belle collided in bad weather around 10 p.m. Both ships were running without lights at the time, and the lookout didn’t see the other ship until it was too late. The Gulf Belle sustained a smashed bow, and the Gulf Land suffered a large hole in its bow. Both ships’ cargoes exploded and caught fire. The sound was heard 50 miles away, the Atlanta Journal reported.

It was simply too much for the crew to try to battle the fire, and the Gulf Belle’s men were ordered to jump into the burning water, from a height of some 35 feet. The wooden lifeboats had burned and those men surviving only had life jackets to keep them afloat. Womack’s commanding officer asked him to stay onboard to make sure everyone on the bridge got off, which he did. Womack, jumping feet first, told a reporter that there were so many men in the water it was difficult to find a spot to jump into.

But the water offered little safety due to the burning fuel. Many of the men were severely burned and couldn’t use their arms or legs to stay afloat. Womack jumped into the wind, where the burning water was less prevalent. He was to spend the next five hours trying to dodge burning oil. Many men, including Womack, ditched their life jackets so they could go underwater to avoid burning flames and inhaling fire. A Coast Guard vessel ultimately picked up the survivors, Womack among them. They were taken to Fort Lauderdale for medical treatment. Although Womack only sustained minimal physical injuries — a blistered back and neck and some scratches — he lost 8.5 pounds during the terrible ordeal.

The crash killed 88 on the Gulf Belle and 43 on the Gulf Land. The Atlanta Journal had reported that many of the man had burned to death, others blown to bits in the explosions. Some bodies were recovered from their bunks inside the Gulf Belle. They never stood a chance.

A Coast Guardsman onboard one of the responding rescue vessels told the Atlanta newspaper that the scene was “hell on earth for those poor souls. We heard screams from way out, and we could help only a little. I saw men freeze on deck, unable to jump. Their clothes were burning and they knelt to pray.”

The Coast Guardsman also said that one of the men they rescued was burned so badly that he begged for something with which to take his own life. “Magazines of both ships were exploding and it appeared like a hailstorm. It was absolutely impossible for anyone to stay alive on either ship.”

But some did survive. Rescuers who boarded the Gulf Belle were greeted by a large dog, the ship’s mascot, which had survived; there weren’t many human survivors, only 21. Only seven survived from the Gulf Land.

Womack’s hometown newspaper, the Americus Times-Recorder, reported that 21-year-old Womack called his mother to let her know he had survived the horrible event. Later, when Womack came to Americus to visit his mother, Alma Adams, that was also reported in the local newspaper.

Womack had forged strong friendships with his gunner mates, and he corresponded with the mother of one who had not survived. Clyde Kelly Ormond Jr., 19, of Houston, Texas, one of Womack’s close buddies, had not met death gently. Womack told his family after returning from the war that on the night of the accident, many of the men in the water were attacked by sharks. There was absolutely nothing that could be done. A story published in the Palm Beach Post revealed that portions of Ormond’s body were recovered from the inside of a 14-foot leopard shark caught off the Miami coast. The FBI used fingerprints from the remains to make a positive identification, and the Miami Sheriff’s Office was notified.

Johnny Womack Jr. marvels at the youth of the young men who served during World War II. “They were only 18 to 20 years old. Can you imagine?” he said. “They were boys.”