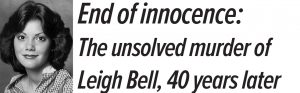

End of innocence: The unsolved murder of Leigh Bell, 40 years later

Published 5:21 pm Tuesday, July 2, 2019

Part 5: New information, and lingering questions

By Beth Alston

AMERICUS — With George Gignilliat having been acquitted of the rape and murder of Leigh Bell on Feb. 1, 1980, the case went cold. But no one forgot about it; it’s been talked about to this day.

Years passed, until around 2000, when a confidential informant came forward. Jerry Smith, in an interview with the Times-Recorder, said he was at the residence of retired law enforcement officer Chuck Hanks, who he knew, to give his condolences on the death of Hanks’ father.

Hanks was also interviewed for this series. At the time, Jerry Smith spoke to him, Hanks was not in law enforcement but working in the private sector. Hanks said Smith told him that he and his former employer and friend, Rodney Collins, would stop work around 3 p.m. and drink every evening. “They became close and trusting of each other and he and Collins would get drunk and Collins would start crying and tell Smith that he has this terrible secret. This would on for a period of weeks or months. Finally, one evening Collins told Smith the story about him going to Farr’s house to buy pot. They’re smoking a joint and drinking beers when in the door come Gignilliat and Leigh Bell. It appeared they were obviously there together. She didn’t appear to be under duress. They all four shared some pot and some beers and at some point, Gignilliat walks into Farr’s bedroom and Leigh Bell follows him in there. He didn’t force her in the room.”

Hanks said, according to Smith, Collins told him there was a loud ruckus coming from the bedroom between Bell and Gginilliat. “Collins said it was so alarming that both he and Farr stood up and looked at each other and Farr actually opened the bedroom door. The door opened against a wall, so Collins couldn’t see into the bedroom but there was some conversation between Farr and Gignilliat about what’s going on, and Collins left the residence.

“This is a problem I have with that, as an investigator,” Hanks said, “Collins should have known that Leigh Bell was in dire straits. He leaves the house because he’s alarmed by what he’s heard. He leaves, goes home and goes to bed. My take on that is, if that was his only involvement … why didn’t he call the police and tell them he had been at Greg Farr’s house and there’s a young lady who he thinks might need some help. Why didn’t Collins call?”

Hanks told the Times-Recorder that he took the information to Sumter County Randy Howard’s office at the old courthouse. As he was telling the sheriff about Gignilliat and Bell coming to Greg Farr’s house, the sheriff stopped him, and said, “Just stop; stop right there. I don’t want to hear any more about it.”

“That kind of shocked me,” Hanks said, “and I asked ‘what do mean you don’t want to hear about it?’” And Howard told Hanks that the Bell family had been through enough and he wasn’t going to put them through it again. “He was very adamant. He didn’t tell me to leave his office but the impression I got was ‘this is it, we’re done.’ It pissed me off. I walked out and told my wife about it.” He told her he didn’t know what to do, that he had evidence, testimony from someone who was given information by an eye witness and the sheriff didn’t want to do anything with it, refuses, doesn’t even want to hear it.”

Hanks still wondered what to do with the information. Knowing that the GBI would not get involved without an invitation of the chief of police or county sheriff, he called the GBI’s local office anyway and was told they couldn’t get involved without invitation. He reminded them that they were already involved in the case from the beginning. They said the sheriff said he wanted nothing to do with it so they couldn’t do anything with it.

The Times-Recorder also talked to Randy Howard for this series. When asked why he didn’t do anything with the new information Hanks had tried to give him, Howard only said that Rodney Collins’ name had “come up early in the investigation.”

Next, Hanks called the Americus Police Department and asked to talk to the chief investigator who turned out to be Nelson Brown. Jerry Smith, the confidential informant, said he went to Nelson Brown’s office, and gave him a statement. Smith said Brown didn’t take any notes but he recalls seeing a tape recorder. Hanks said Brown called him to let him know the interview had taken place. When contacted for this series, Brown, now an Americus City Council member, said he didn’t recall ever interviewing Jerry Smith and that he wouldn’t have anyway because it “wasn’t proper protocol.” There is not a report, supplemental report, notes, or tape in the case file regarding a statement from Jerry Smith, as examined by the Times-Recorder.

Finally, some movement

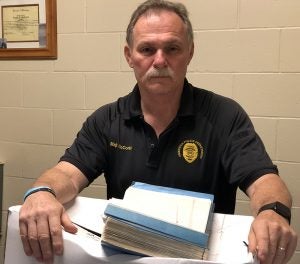

Move forward now to 2015. Five years have passed and nothing as ever been done with the new information. Hanks returned to work in law enforcement, and was an investigator with the Sumter County Sheriff’s Office. He visited with Maj. Richard McCorkle, who heads up the criminal investigations division of the Americus Police Department (APD). They decided to take another look at the Bell case. The two agencies have identical case files. McCorkle located the one at the APD but it took months to locate the case file for the sheriff’s office which was ultimately located in the “old Tog Shop” building which the county acquired for office and storage place. The two went through the files and talked and compared notes and talked some more.

Hanks and McCorkle arranged to interview Rodney Collins at his home on the Crisp County side of Lake Blackshear. Hanks said Collins told them he had no idea what they were talking about. “We explained to him how the law works, that this is a murder investigation and you don’t have to say anything to us at all,” Hanks said. They told Collins, “At this time, we think you’re a witness. Otherwise we’d advise you of your rights. But because this is a murder investigation, a felony investigation, if you lie to us and we can later prove that you lied to us, then you can be charged. He [Collins} still said he had no idea,” Hanks said.

Hanks said when he and McCorkle arrived back in Americus, he dropped McCorkle off at his office at the APD before driving back to the sheriff’s office. “No sooner had I gotten back to my desk, the phone rings and it’s Richard and he says he just got a call from Rodney Collins and he says he got to thinking about it after they left and he did remember something about that night.”

At that point, they got the GBI involved again. Hanks said he went to his then-supervisor, Maj. Ralph Stuart who was very reluctant for Hanks to be involved in the case at all. “I would have to go around him or over him,” Hanks said. So he went to Sumter County Sheriff Pete Smith and Chief Deputy Col. Eric Bryant. Pete Smith told the Times-Recorder, “I told him if he had any compelling evidence, we’d reopen this case. Technically the case was still open, having never been officially closed.” Hanks was given permission to continue to work the case with the GBI and to keep it on the QT but not to mention it to Ralph Stuart unless he asked about it. Stuart was fired from the sheriff’s office in April 2019, after he was charged with simple battery and sexual battery, both misdemeanors. He has yet to come to trial.

The interviews

The Times-Recorder requested records from the GBI under the provision of the Georgia Open Meetings and Records Act. The following information comes from interviews with Collins and Farr by the GBI.

On July 31, 2015, GBI Special Agent Mike Walsingham and Sgt. Chuck Hanks started at square one and interviewed the confidential informant, Jerry Smith at the Sumter County Sheriff’s Office. Smith reiterated what he had told Hanks and McCorkle before. Collins told him about Gignilliat and Bell having “a consensual, ongoing, sexual relationship.” Smith told investigators that while Collins was talking to him, Collins’s girlfriend, whose name he could not recall, told Collins “That’s enough … be quiet” and to stop talking about that. Smith said Collins referred to Farr as his “best friend.”

That same day, July 31, they interviewed Rodney Collins who reiterated that he had seen Gignilliat and Bell at Greg Farr’s house on June 6, 1979, the night Bell disappeared. Collins also told them he and is family lived next door to Farr on Pine Avenue in Americus but he didn’t “hang out” with Farr. He also told them that about a week prior to Bell’s disappearance he and his father pulled into their driveway and observed Gignilliat and Farr with two females, one age 15 or 16, the other around 20, walking from the house to a car. Collins described one of the girls as beautiful and that she was wearing red shorts and red suspenders with a white t-shirt. Walsingham showed Collins a photo of what Bell looked like when she disappeared and Collins said it looked like the the girl he had seen.

Collins also told the GBI agent that he had not seen Greg Farr since 1979, but had seen a friend request from Farr on Facebook a couple of months prior to this interview. Collins told the GBI that Farr knows what happened to Bell, and mentioned the fire at Farr’s house. Collins also told the agent that he had never provided any of this information to law enforcement before because he had never been asked and had never volunteered it. When asked if had observed Gignilliat and Bell at Farr’s residence having an argument about a sexual act, he initially denied it. When asked if he would submit to a polygraph, Collins said he “vaguely remembered” something about it. Collins said he did not recall seeing Gignilliat and/or Farr enter a room with a female while he was present at Farr’s house. He agreed to submit to a polygraph.

Take two

Collins was interviewed again by Walsingham and Hanks on Aug. 14, 2015, at the GBI Region 3 Office in Americus. Collins told them that a couple of days after he had taken an unidentified male to Farr’s house to purchase marijuana from Farr, “in or about June 1979,” he was at a friend’s house, Harold Clifton, when an unknown male and female, possibly two females, come to Clifton’s residence, asking where they could buy pot. Collins said he did know but didn’t want to go there, but drove to Farr’s residence to purchase the pot. He told the authorities it was around 2 or 3 p.m. Upon entering, he said he saw Gignilliat and a white female, thin, approximately 5’4” with short brown hair, seated next to Gignilliat. He said he thought it was the same girl he had seen in the driveway a couple of weeks prior. While there, Collins said, he purchased the bag of marijuana from Farr, and a marijuana cigarette was passed around and everyone smoked it, including the girl. Collins said he had been at the Farr residence for about 15 minutes when Gignilliat and the girl walked into a bedroom and shut the door. He advised that a couple of minutes later, he heard the female say, “I don’t like it that way” and that she “got loud.” He said Farr walked to the bedroom door and went in. Collins said that’s when he left through the back door. He told the investigators he never spoke to Farr again about the matter.

When investigators asked Collins why he left the Farr residence, Collins said he left because he knew that Gignilliat was a “nut.” Collins also told then that he later told his father about the observation and his father told him he had nothing wrong and “it was best if he did not tell anybody about the matter and forgot it.”

Collins told them a day or two later he saw the attractive female wearing the red shorts and suspenders in front of Farr’s residence again. He thought it was the same female he saw go into the bedroom with Gignilliat. He said he did not believe the female died the day he saw her entering the room with Gignilliat.

Collins agreed to attempt “a controlled call” to Farr to corroborate is statement. That call went to voicemail, after Farr identified the number and his name, and Collins left a message to call him back. Walsingham advised Collins that if Farr returned his call not to answer but to contact Hanks immediately. Collins agreed to submit DNA samples, which he did.

Greg Farr interview

On June 14, 2017, GBI Special Agent Rhett Moore and Lt. Hanks traveled to Columbus to the residence of Greg Farr, to ascertain if Farr had any information about the Bell case. Agent Moore, in his report, summarized what Farr stated:

- No one ever mentioned arson being the cause of a 1979 fire that occurred at Farr’s residence in Americus; Farr was in Ellaville at the time of the fire and returned home after the fire.

- George Davenport, Leigh Bell’s half-brother, lived with Farr in the house that burned down. George Gignilliat had only been to the residence on one occasion.

- Gignilliat, Farr, and Davenport played on the same softball team. Gignilliat came over to Farr’s house after a game and the three drank beer but didn’t smoke anything. Gignilliat and Davenport got into a fight when Gignilliat “sucker punched” Davenport. Farr threw Gignilliat around the house and told him to leave.

- Farr would be willing to submit a DNA sample. Farr had nothing to with Leigh Bell’s murder.

- Farr went to high school with Rodney Collins. The two were not friends or enemies and Farr had not talked to Collins in years. Farr never received any calls or voicemails from Collins. They never had any issues in high school and there was no “bad blood” between them.

- Farr never used or sold marijuana or other drugs.

- Collins lied because Collins had never been in Farr’s residence.

- Farr said the media covering the Bell case confused Davenport and Gignilliat.

- Farr said he thought he passed a polygraph in the past. When Farr was asked if he would be willing to take a polygraph test then, he shut down the interview.

Primary source: Collins

The Times-Recorder also talked with Rodney Collins for this series. He told the newspaper, in a telephone interview, that he had been at Farr’s the night Bell disappeared. He said he was there only about 15 minutes because he had people waiting on him. When the ruckus was heard coming from the bedroom, Collins said, he told Farr he needed to do something about it. Farr entered the bedroom and Collins left the residence. “That’s the last time I saw her or him,” he said.

“I thought Gignilliat was like [Charles] Manson,” Collins told the newspaper. “Something wasn’t right.”

Collins said he might have looked at “that girl” half a second and he thought she was wearing a red shirt. She went to the bedroom of “her own accord,” Collins said. He said after he left Farr’s residence, he put it out of mind and went on. Collins said he went to school with Farr but didn’t “run around with him” and “didn’t say more than 100 words to him in my whole life.” Collins said Farr was “more popular” than he was.

“You need to let them know that little girl went out with him [Gignilliat]. Once when she was wearing a green-brown shirt and the time I saw her at Greg’s.”

“I never did make eye contact with Gignilliat,” Collins told the Times-Recorder. “I was scared to death of him; I’d heard all the things about him. … If somebody had asked me [about seeing Gignilliat and Bell at Farr’s house], I would have told it,’ Collins said. “I couldn’t believe the police didn’t come to the neighbors and ask questions. … I didn’t want anyone to think I was involved, because I wasn’t.”

Collins called the Times-Recorder back shortly after the interview, expressing concern about the series, asking who else was being interviewed and when it would be published. He said, “I’m the last man standing, and I will catch all the repercussions for it.”

Another version

Tim Lewis, a former assistant district attorney for the Southwest Judicial Circuit, said Collins mentioned this to him in May 2016. Lewis, interviewed by phone recently, told the Times-Recorder that the subject of Leigh Bell’s murder came up in conversation and Collins told him that he had been at Greg Farr’s house the night Bell went missing, that he had seen Gignilliat and Bell there and they went into a bedroom. Collins told Lewis that he and Farr were snorting cocaine, and when they heard Bell scream, Farr went to the bedroom door and Collins left the residence out the back door. Lewis also said Collins told him that he had been telling authorities this story for years but no one ever did anything. Lewis said he took the information to then-District Attorney Plez Hardin shortly after but Hardin told him the office had neither the personnel nor the funding to pursue it. Hardin committed suicide in April 2018.

Collins told the Times-Recorder that he never told Lewis or anyone else this story because he had only been to Greg Farr’s house once and it was “in the middle of the day,” and he’s never done cocaine.

Unanswered questions

Hanks said from the start of this series that this is not about himself or Richard McCorkle. “It never has been. Richard and I have spent nearly 40 years trying to get the truth out.”

“This case has haunted me for 40 years,” Hanks said. “We finally have closure but we will never have all the facts. If they had interviewed Rodney Collins 20 years ago, they may have gotten to the bottom of it. There is no guarantee they would, but now everyone except our confidential informant and Rodney Collins are dead.

“My only goal in continuing the investigation was to see justice done and to bring closure for the Bell family. I know we don’t have all the answers but we are closer now than we’ve ever been.”

Missteps

“From the start, this case was not handled properly,” Sheriff Pete Smith said. “I’m not throwing the blame on anybody.”

“I’m 99 percent sure it was George Gignilliat …” he said, “but the tainted evidence … Like I said I’m not throwing anybody under the bus but if I’d handled it, it would have been different. I’m not saying I’m smarter than anybody else involved, but …”

While law enforcement did not have the technology in 1979 that they have today, Sheriff Smith said they did have “common sense” in 1979.

Where’s the physical evidence?

One question that is asked by many is: what ever happened to the physical evidence such as hairs, swabs, clothing, blood sample, fingernail scrapings, etc., that were sent to the State Crime Lab? McCorkle, of the Americus Police Department, told the Times-Recorder that none of that was ever sent back to the APD because the sheriff’s office was the lead investigative agency in the Bell case. Former Sheriff Howard told the newspaper that it never came back to his office so it must be at the State Crime Lab. The GBI said all the physical evidence and forensic reports were returned to the sheriff’s office. So, it does not exist for practical purposes.

Former Sheriff Smith said even if the physical evidence was still available, it was contaminated from the start due to Bell’s body having been wrapped in a blanket. “When I put Dr. [Larry] Howard [head of the State Crime Lab] back on the airplane [after having performed the autopsy on Bell’s body], you could have touched him ([makes motion as if getting burned and sizzling sound], he was still hot. He was upset and he was mad.”

The sheriff also commented on how the murder affected the community, saying that children were no longer allowed to play outside and there was a feeling of general fear. “Everybody was suspect,” Smith said. “I don’t know how that family [the Bells} absorbed her, and her sister, and her older brother.”

The Bell family

Leigh Bell’s parents, Leland and Catherine Bell, 85 and 80, live in Birmingham, Ala., near their eldest daughter, Cathy and her family, having moved there from Americus in 1990.

Catherine Bell talked with the Times-Recorder by phone for this series. She said it is just as fresh today as it was 40 years ago, “and every day,” she said.

A plaque in memory of Leigh Bell is located in the main lobby of Americus Sumter High School on Harrold Avenue. It shows the Class of 1982, of which Bell would have been a member had she lived.

“I want closure on it,” Catherine Bell said. “I wanted someone to pay for it. Nobody did. It was disappointing to us when they found him [Gignilliat] not guilty, and then nothing else was done about it. I don’t think they did anything about it in 40 years. Maybe they talked to somebody about it. It just blows my mind that nothing ever became of it. And when they went to trial they didn’t have enough evidence to convict anybody on. I think they just wanted to hurry it and get somebody arrested and over with.

“All along I’ve known that, and so have other people, and if George Gignilliat did it, he had help. He couldn’t have done it by himself. He was a transient here from Warner Robins. I don’t know how long he had been in Americus. I know it was Debra Slaughter’s car and he had help.”

About the closing of the case, Catherine Bell said that no one had ever told the Bells anything about it. She said she called the Americus GBI office in February and talked to Terry Howard, who is now special agent in charge, and asked about the cold case. “I was trying to see about the DNA. I had seen it on TV and heard that things 40 or 50 years ago were tested for DNA and found results.”

She said she also called the sheriff’s office and asked who was in charge of cold cases, and someone told her the GBI and she was transferred to Terry Howard. He told her he would look into it and get back to her. She said she waited a week and she called him. Howard told her that a prime suspect had died. She said this was news to her and she asked who it was. She said Howard told her he would get back with her. He called her the following day and told her the Americus Police Department was in charge of the investigation. The next day she traveled to Americus and talked with Maj. Richard McCorkle, who heads up the criminal investigations division of the APD.

She said she was told by McCorkle that the last suspect, Greg Farr, had died recently. He died in January, according to Facebook posts by his sister. Catherine Bell said she considers it “very coincidental” that Farr’s house burned soon after the crime and it was never followed up on.

She is still bitter, and understandably so. She said she doesn’t know how nothing could have been done on the case since Gignilliat’s acquittal. She cried during the interview with the Times-Recorder, tears of frustration.

“Seems like everybody’s gone,” she said, “but they weren’t gone 10, 20, or 30 years ago, were they?” Of Rodney Collins’ and Greg Farr’s stories, she asked, “How do all those people live all these years, and have it on their mind?”

Basically, Catherine Bell feels that justice was not done and that the investigation was not handled properly. “They botched it all the way around,” she said. “It looks like they would have been more careful with something as important as the DNA evidence; maybe they did something with it.” She said she thought it was a mistake to take out the sitting district attorney and put in a special prosecutor on the case. “But what did we know?” she asked. “But I think it was a mistake.”

While former Sheriff Randy Howard told the Times-Recorder they did the best they could on the investigation with what they had, Catherine Bell still says they didn’t know what they were doing. And no one even called to tell them that the case had been closed by District Attorney Lewis Lamb.

The Bells are no strangers to loss. Her son George Davenport had been a diabetic since age 8, and died of a heart attack when he was 44. Leigh Bell’s younger sister Melanie Bell leapt from the Stratosphere in Las Vegas at age 36.

And now the parents will never have any answers to the questions they’ve had for four decades. Being the believers they are, it can only be hoped that some sweet day when they see their daughter Leigh again, all will be revealed.