Evan Kutzler: The grave digger, the Labor Day petition, and the Great Migration

Published 9:50 pm Friday, September 6, 2019

- The Lewis family home in 1919, located at 612 Oglethorpe Ave., in Americus.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Evan Kutzler

Money weighed on Charles Lewis’s mind as Labor Day approached. His salary as sexton of Eastview Cemetery was only 60 percent of what the white sexton at Oak Grove Cemetery made. He knew this because local government salaries were public information published in the Americus Times-Recorder. When he started the job in 1911, his salary was only half the white sexton’s pay. Lewis picked Sept. 1, 1919 — the nation’s 25th annual celebration of Labor Day — as the moment to appeal for a better deal.

His timing was significant. Lewis’s Labor Day petition coincided with larger racial and class tensions shaking the country in 1919. The U.S. government inferred an international communist conspiracy when four million American workers participated in strikes from Washington to Maine in steel mills, coal mines, and beyond. Alongside the labor strikes and government investigations that made up the “Red Scare,” racial violence flared up in bloodshed that became known as “Red Summer.” Race riots in northern cities claimed the lives of more than 250 people. Near Elaine, Arkansas, whites killed more than 200 black men and women who had decided to form a labor union. In Putnam County, Georgia, whites burned six black churches. It took courage, an understanding of national events, and a strong sense of justice for Lewis to protest his wages amidst this unrest.

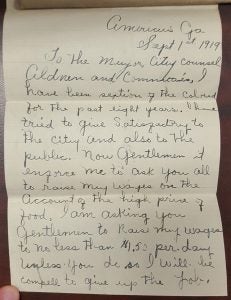

Charles Lewis’s Petition, Sept. 1, 1919. Americus City Council Records, Municipal Building, Americus, Ga.

The petition Lewis sent to the mayor and the city council is notable for its mentions as well as its omissions. “I have been sextion of the colored [cemetery] for the past eight years,” Lewis reminded them. “I have tried to give Satisfactrey to the city and also to the public.” After establishing the duration and quality of his labor, Lewis outlined the problem. Rather than stating the obvious racial discrimination, Lewis used the price of food to frame his argument. “Now Gentlemen,” he continued, “it enforce me to ask you all to raise my wages on the account of the high price of food.” Lewis asked for $1.50 per day.

In calculating that figure, Lewis made a political calculation. If the city council consented, his monthly salary would increase from $30 to $45. Still, it would not match the white sexton’s monthly salary of $50. This caution suggests that Lewis thought about his audience. What did the white men in authority want to hear? What would they consent to? What would provoke backlash? Yet knowing his audience, their prejudices, and anticipating their reaction did not mean that Lewis was groveling. He reminded them of his freedom to walk away. If they did not raise his salary, Lewis declared, “I will be compel[ed] to give up the job.”

The confidence Lewis projected in his ultimatum may have come from previous work experiences and his middling socio-economic status. According to census workers, Charles Lewis and his wife, Rachel, lived in Americus at the beginning of the century. While Rachel worked at home as a laundress for years, Charles frequently changed jobs. He worked as a railroad laborer and then as a carpenter. They also moved around and purchased property. One year the Lewis family lived at the corner of Forsyth and Poplar streets. In 1910, Charles and Rachel Lewis owned the house at 612 Oglethorpe Ave., and lived there with seven children ranging in age from 11 months to 17 years. The Lewis family lived in this house the full nine years that Charles worked as the cemetery sexton.

Being the sexton of Eastview was a difficult but important job. It required the confidence — and the votes — of an all-white city council. The sexton’s duties in a town the size of Americus probably included administrative tasks as well as the physical act of grave digging. One of the first burials was of his own son, Solomon Lewis, who died in February 1911, at the age of four. The cause of death went unrecorded. Other burials included the human remains of awful racial violence. In October 1912, a deputy sheriff dropped off the bullet-riddled body of Babe Yarbrough, a black man accused of attempting to assault a white girl. The city made no serious inquest into the lynching. The murderers were not brought to justice, and the job of burying one of the city’s open secrets fell to Lewis.

While the petition is notable for its clear perspective, the understandable caution, and the confidence, other sources of information Lewis’s life are tougher to interpret. The smattering of documentation — census records, city directories, a debt security, and city council minutes — all contain information written about but not by Charles, Rachel, or their children. Estimates on his year of birth ranged from the 1860s to the 1870s. More troubling, the census takers in 1900, 1920, and 1930, listed Charles Lewis as being unable to read or write. Was this an error? A racist assumption? While being a sexton probably required the ability to read and write, it is possible that Charles Lewis was illiterate. When the Lewis family borrowed against their home in 1914, it was Rachel — not Charles — who signed the debt security. The 1919 petition was the voice of Charles Lewis. It is possible, though not certain, that Rachel served as the ghost writer.

The Americus City Council met the same day Charles, perhaps with the assistance from Rachel, asked for increased pay. They read the petition and then promptly voted to authorize the chairman of the Cemetery Committee to “fill [the] vacancy should said Chas. Lewis resign.” Then the council turned to a second Labor Day petition, which also asked for higher wages, from the city’s all-white fire department. Were the two petitions coordinated? The city council sent the second petition to the finance committee for investigation. From all appearances of that Labor Day meeting, the city council prepared to give the white fire department raises while calling the black sexton’s bluff.

The city council backed down, or, at least, they took a softer stance. Two weeks later, they approved raises for all city positions, both white and black. The mayor’s monthly salary increased from $60 to $75. The firemen’s pay increased from $70 to $90 per month. The two city sextons each received a $10 raise. Beginning October 1, 1919, Lewis’s salary increased from $30 to $40 per month, and the white cemetery sexton’s salary increased from $50 to $60. The raise was $5 below what Lewis had requested in his petition.

The Great Migration

It took another year, but Lewis kept his promise to leave the job if he did not receive the full raise. When he gave up his sexton duties, he also moved his family from Americus to Buffalo, New York. The Lewis family was not alone. Their decision to leave Georgia coincided with the first national wave of the Great Migration. From World War I to World War II, more than one million African Americans left southern states in search of a better life in northern cities. Sumter County was a microcosm of this larger pattern. The black population of Sumter County fell by 3,953 people (19 percent) between 1910 and 1930. Eight of those men, women, and children who left were members of the Lewis family.

It is unclear whether the family found a better life in New York. While Charles Lewis found work as an iron worker in a steel plant, the family did not purchase a home in Buffalo during the Great Depression. One possible reason was the discriminatory federal lending policies that made it more difficult for black families to buy homes. It is also unclear whether any family members returned to Georgia. Charles died in Buffalo in the 1930s. Rachel and most of her adult daughters continued to live together in that city until at least 1940. When Rachel finally sold the house on Oglethorpe Avenue in 1942, it may have cut the family’s last tie to Americus.

Charles Lewis’s petition opens a window into the daily life of one hardworking man who asked for a better deal. The original document is located with the city council minutes at the Americus Municipal Building in downtown Americus. In setting up an appointment to look through city records, I admitted to City Clerk Paula Martin that I did not know what I was hoping to find. Entering the old vault that serves as an archive and glancing through the records confirmed what I have come to expect: local records are unpredictable, but they contain treasure. The petition is just one of the gems. It is at once a personal appeal, a public protest, and one moment in a family’s decision whether to stay in a place once called home or look for better opportunities elsewhere. It is a local Americus story, sure, but it is a wider American story as well.